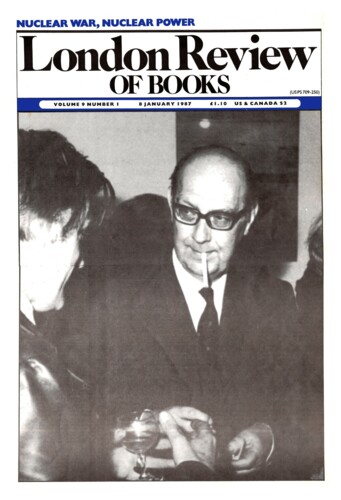

Solomon Tuesday

Rosemary Ashton, 8 January 1987

Coleridge has always been our representative Romantic literary critic, and Matthew Arnold has long been thought of as the type of the Victorian critic. There is, perhaps, no need to topple Arnold from his eminence, but it is high time that a close competitor was brought out from the shadows where he now lurks, uncollected and unread. For Richard Holt Hutton was a prodigious and impressive critic. And unlike Arnold he made literary (and theological) criticism his profession. Hutton was the author of about seven thousand reviews and essays. He edited the Spectator from 1861 until his death in 1897. Like Jeffrey, first editor of the great Edinburgh Review in the early part of the century, he read for the Bar, but unlike Jeffrey he never practised law, choosing to devote all his time and attention to literary journalism. In more ways than this, too, he was typical of the progressive movement, during the 19th century, away from the uniformity of Oxford or Cambridge-educated professional men who undertook reviewing as a gentlemanly pastime. As a Unitarian in his youth, he was debarred from taking a degree at either of the universities, and became one of the first distinguished generation of Victorian intellectuals to be educated at University College London, which was founded on the German system guaranteeing freedom of opportunity and learning to dissenters from the established Church. He even spent some time studying at the University of Bonn, one of the institutions which served as a model for University College.