Double Life

Robert Taubman, 19 May 1983

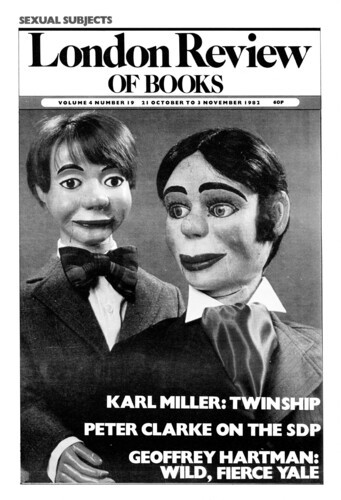

Like a Victorian novel, The Philosopher’s Pupil ends with a valedictory coda. Good-bye Emma, good-bye Pearl. They have ‘become (and I predict will steadily remain) fast friends, bringing a lot of affection, happiness and wisdom into each other’s lives’. It’s an amiable convention, pretending that these are real people, and that ‘affection, happiness and wisdom’ are real values and not just a touching illusion. But it’s only a pretence, considering what the preceding 500 pages have done to knock any meaning out of such words. Iris Murdoch juggles with reality and illusion, playing with the possibilities of ‘as if’; and there’s some mockery of her puppet-characters in the assumption of this coda that they could ever merge into real life.