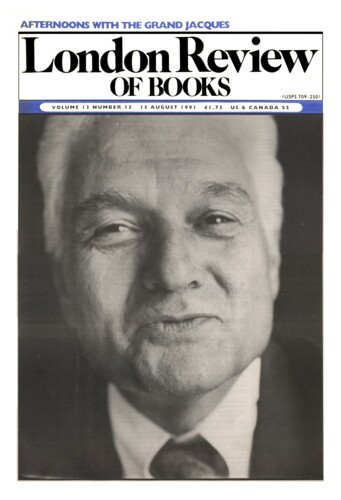

Finest People

Penelope Fitzgerald, 3 December 1992

In 1944 GBS was a widower of 89, dying, as we like celebrities to do, in public, and still in receipt of hundreds of letters every month from admirers, enquirers, beggars and cranks. They were in search, sometimes of money, more often of sympathetic magic. To many of them Shaw sent printed reply cards which he had ready on a wide range of subjects.