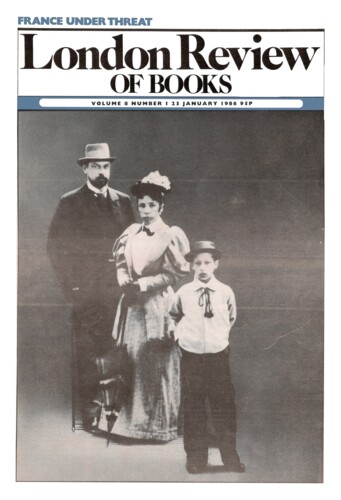

‘Stravinsky’

Paul Driver, 23 January 1986

Stravinsky was a dull correspondent, but at least he was Stravinsky. His wife’s letters to him, which preponderate over his to her in Robert Craft’s new selection of Stravinskyiana, Dearest Bubushkin, have biographical importance but do not all that frequently rise above the level of any wife to any husband. The book, though physically attractive and lavishly illustrated, is a hard read. What is it that keeps one going through a long sequence of letters with their arbitrary reference to time and place and their detailed personal content? Usually their literary value and/or narrative arrangement. Vera Stravinsky’s letters have more of the former than her husband’s, but that isn’t saying much. Craft’s arrangement of the material is chronological (1921 to 1954) but creates little suspense because, by and large, it is the recipient, not the author of the letters who is doing that, away from home on his adventures. Nor can the moderately enlivening format of the Selected Correspondence (of which the third and final volume is now published) be used to parcel up correspondences and themes: for Vera there is only one correspondent, and only one theme – marital solicitude.’