Patricia Craig

Patricia Craig whose books include The Lady Investigates: Women Detectives and Spies in Fiction, written with Mary Cadogan, is working on a study of Northern Irish poetry and fiction.

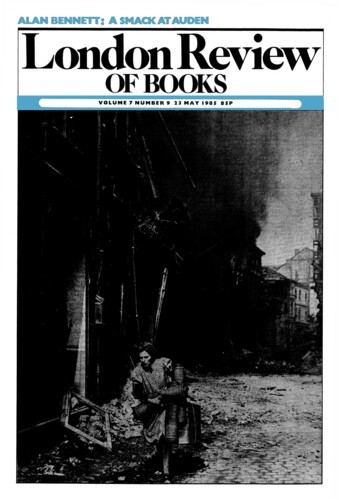

Exasperating Classics

Patricia Craig, 23 May 1985

Peter Llewelyn Davies, one of J.M. Barrie’s ‘Lost Boys’, in later life called Peter Pan ‘that terrible masterpiece’. Brigid Brophy, having reread Little Women and its sequels, dried her eyes and blown her nose, resolved that ‘the only honourable course was to come out into the open and admit that the dreadful books are masterpieces.’ She did it, though, ‘with some bad temper and hundreds of reservations’. It isn’t an uncommon reaction. These works, and many others, are among the exasperating classics of children’s literature which affect you at some level in the way the authors overtly intended, for all your rational revulsion or boredom or disapproval of the outworn ideologies they may sanction. The last dissenting emotion is perhaps the one most frequently aroused at present. Children’s stories from the past are continually disparaged for being insufficiently egalitarian, or wide-ranging, or whatever. Robert Leeson, in Reading and Righting, is struck by the failure of children’s authors before the 1960s to represent the working classes satisfactorily in their fiction. He claims a kind of ‘cultural invisibility’ overtook the proletariat, and traces this deplorable disappearance right back to the late 15th century and the start of printing. Along with the ancient folk tale, transmitted orally, went a proper respect, imaginatively expressed, for everyone’s social role. Then the powerful middle classes, into whose clutches the rudimentary book trade fell, proceeded to impose their own view of things on the developing literature.

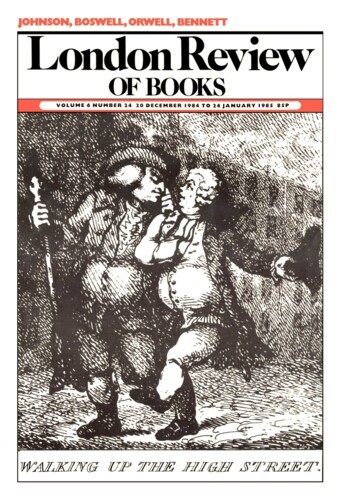

Uncle Max

Patricia Craig, 20 December 1984

Like most biographers, Anthony Masters starts by announcing his subject’s date of birth; unlike most biographers, he gets it wrong. Charles Henry Maxwell Knight was born on 9 July 1900, not 4 September, under the sign of Cancer, not Virgo, however tempting it may be, for reasons which become clear in the course of the story, to assign him to the latter. Information about Maxwell Knight is pretty scanty and unreliable at most stages of his life, but a copy of his birth certificate may be obtained from the usual source, and was surely worth looking at; it is also more precise about Knight’s place of birth than Masters has chosen to be, specifying 199 Selhurst Road, South Norwood, Croydon, while he leaves it vaguely at Mitcham, Surrey.

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.