The man who was France

Patrice Higonnet, 21 October 1993

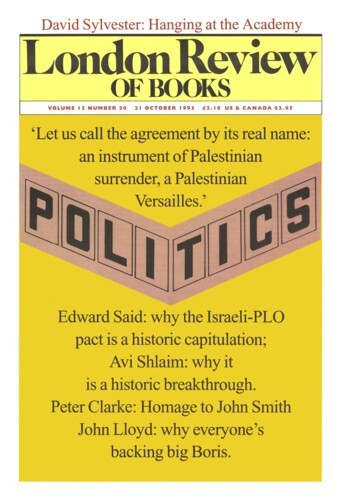

Clemenceau was an archetype; he even looked like the Third Republic. He wore, in Keynes’s words of 1919, ‘a square-tailed coat of very good, thick broadcloth, and on his hands, which were never uncovered, grey suede gloves’. For Churchill, who much admired his French counterpart, Clemenceau was ‘as much as a single human being, miraculously magnified, can ever be, a nation; he was France.’ And so he was, but the trouble is the Tiger was also dead-set against many features of modern life, from political parties and feminism to trade unions and telephones. An archnationalist and – in the end – an unwitting belliciste, he was the evil genius behind the destructive peace of 1919. It is too bad that Gregor Dallas in his long biography has so little to say about these matters. For him, Clemenceau was ‘the man who led them’ – the ordinary soldiers of the First World War – ‘and their allies’ (who does Dallas have in mind?) ‘to victory in 1918. And a victory it certainly was.’ No it wasn’t: 1914-18 was a disaster all around, and so was Clemenceau’s handiwork – the Versailles Treaty of 1919. The break-up of the central empires which it ratified brought us Hitler; the Russians’ share was Lenin; and the legacy of the Ottomans is still being fought over, from Iraq and Palestine in the Middle East to Sarajevo today and Kosovo tomorrow.’