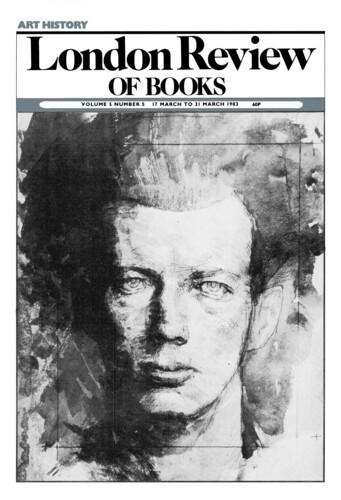

Hand and Mind

Michael Baxandall, 17 March 1983

Both these books are art books in the particular sense that the main reason for paying quite large sums for them would be their illustrations. This is not to say their texts are bad. Both are by distinguished Dürer scholars and both offer tidy brief versions of the academic consensus without any eccentricities. Anzelewsky proceeds chronologically: after a first short chapter on Nuremberg he works through Dürer’s career in ten uncontroversial phases, Strieder goes by topic: ‘personality’, writings, ambience, influences, subject-matters, techniques – he was director of the great quincentenary Dürer exhibition in Nuremberg in 1971, and the arrangement reminds one a little of that. Anzelewsky has the more enterprising bibliography. Strieder offers two appendices by other hands, one a short technical analysis of the facture of the Four Apostles in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the other a good explanation of Dürer’s use of systematic linear perspective. Both Anzelewsky and Strieder are quite all right, but neither is comparable – for fullness, denseness and communicated struggle to engage and fathom – with Erwin Panofsky’s Albrecht Dürer of 1943, still the best book.