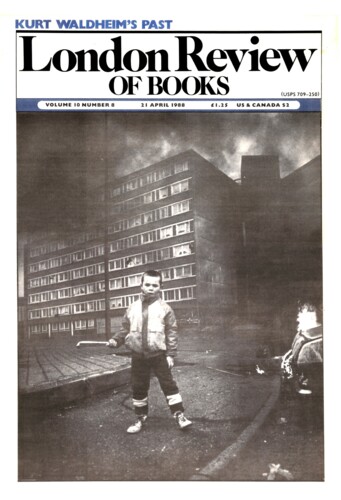

Kureishi’s England

Margaret Walters, 5 April 1990

The ‘beautiful laundrette’ that provides the title for Hanif Kureishi’s first film catches the flavour of his very personal brand of humour – off beat, off-the-wall with a cynical twist. Indian teenager Omar, working for his uncle while he waits to go to college, takes over a dingy, run-down laundrette, and tarts it up – with orange walls, fish tanks, hanging ferns, muzak and a glittering, picture-palace neon sign – till it’s ‘a ritz among laundrettes’. He hustles, steals from his family, and bosses his white friend Johnny into doing the dirty manual work, then stages a grand opening ceremony, champagne corks popping while eager customers queue outside. (The movie has quite a lot in common with that notorious strip-teasing Levi’s ad: Omar knows a launderette is a refuge from the drab, lonely streets, a meeting-place that promises entertainment and sexual or at least voyeuristic excitement.) Kureishi gives an exuberant account of one South London kid who makes his kitschy fantasies come true; at the same time, his movie is a chilling anatomy of a Thatcherite businessman in the making, and already on the make.’