Torturers

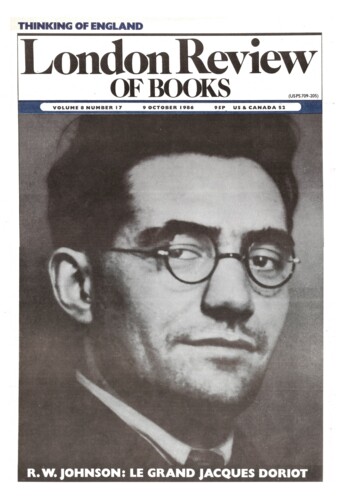

Judith Shklar, 9 October 1986

Books and films about terror and torture are now both more numerous and better than they used to be. The reasons for this are probably bad news. There is more to talk about. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to find a volume as solid and responsible as Edward Peters’s Torture, which traces the history of torture from the extraction of evidence from slave witnesses in criminal trials to the Inquisition, and on to its use, after a brief interruption, in our century as part of the ideological wars of nation-states with their fear of subversion and the importance they attach to intelligence. He says less about political terror, but that also has been properly recorded by now. Not the least value of Peters’s book is its bibliography, which is to be recommended particularly to anyone reading Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain, so that they can find out what Amnesty International and similar human rights organisations do and why their work is so important. For in spite of the ecstatic quotes on the blurb and the author’s own introduction to the book, only a few of its pages are concerned with torture, and these are at best misleading.