Ian Gilmour

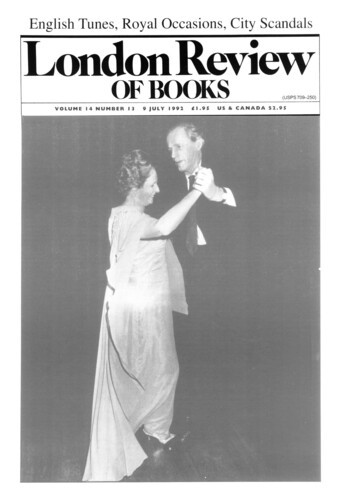

Ian Gilmour edited the Spectator in the 1950s when Karl Miller, the founding editor of the LRB, was its literary editor. He became a Conservative MP in 1962 and was Lord Privy Seal for the first two years of the Thatcher government. A Tory ‘wet’, he wasn’t sympathetic to her policies and regretted not resigning before she could sack him. His books include Dancing with Dogma: Britain under Thatcherism (a picture of Gilmour and Thatcher dancing together can be found on the cover of the LRB of 9 July 1992) and The Making of the Poets: Byron and Shelley in Their Time. He died in 2007.

Advice to the Palestinians

22 December 1994

My Israel, Right or Wrong

Ian Gilmour, 22 December 1994

The foreign policy record of the Clinton Administration has been dismal. Even when the United States has shown more sensible and decent inclinations than Europe, as over Bosnia, the White House has failed to evolve and stick to a consistent policy, leaving an impression of bungling vacillation. In one area, however, the Administration has not only claimed credit for success but has sometimes been awarded it; astonishingly enough, that area is the Middle East. This book enables us to examine that claim and much else besides, because War and Peace in the Middle East is a critique of American policy from the end of the Second World War. Avi Shlaim is well known to readers of this journal, who will be aware that nobody is better fitted for the task. A member of the revisionist school of Israeli historians, he is a rigorous and fearless scholar who follows the truth where it leads him. A few years ago Shlaim wrote a massive classic, Collusion Across the Jordan; here he shows himself to be equally skilled as a miniaturist. His book is a masterpiece of compression, which should now have a British publisher.

Napoleon was wrong

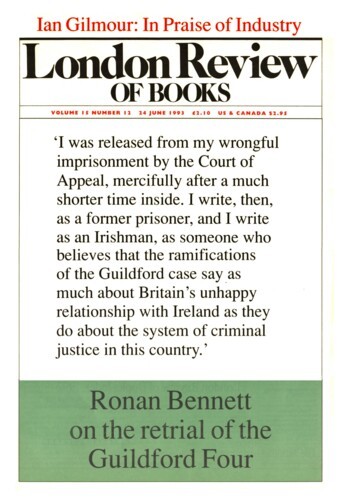

Ian Gilmour, 24 June 1993

Britain emerged from the war still unquestionably a great power, its Prime Ministers Churchill and Attlee considered the equals in negotiations for the post-war settlement, of America’s Presidents Roosevelt and Truman and Soviet dictator Stalin at the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences of 1945.

No thanks to the liberal revolution

Ian Gilmour, 9 July 1992

For thirty years after the war Britain had full employment, stable (if slow) growth, low inflation, and a welfare state that was widely admired. And it was common ground that governments could and should provide those things. Since the mid-Seventies, all that has changed. The norm for unemployment has risen five or sixfold from about half a million to nearly three million; growth is slow and uneven, inflation is stubbornly higher than in the early post-war period; the provision of public services has markedly deteriorated; and new disparities in the distribution of income and wealth have opened up. Instead of being shocked by these changes, many people seem disposed to think that they are all for the good, or, at least, that there is nothing that can be done about them.

Pieces about Ian Gilmour in the LRB

Hail, Muse! Byron v. Shelley

Seamus Perry, 6 February 2003

Ian Gilmour’s deft and learned book is concerned with the lives of Byron and Shelley up to the morning on which Byron woke up and found himself famous. The poets weren’t to meet for...

Why One-Nation Tories can no longer make an impression on the political establishment: Gilmour’s Way

Ross McKibbin, 16 April 1998

Ian Gilmour is one of the most leftwing figures in British politics: a feat he has achieved by not moving. He remains upright amid the ruins of a Keynesian political economy while the two major...

Stormy and prolonged applause transforming itself into standing ovation

Ross McKibbin, 5 November 1992

Ian Gilmour could scarcely have timed the publication of this book better. The last few weeks really have been a Marxist ‘conjuncture’: a heightened moment when social realities can no...

Not Many Dead

Linda Colley, 10 September 1992

Ian Gilmour is a distinguished and highly intelligent example of a once rare species: he is a Conservative with a cause. Unfortunately for him, however – and perhaps for the rest of us as...

Leaving it alone

R.G. Opie, 21 April 1983

Sir Ian Gilmour has written a splendid book about a splendid subject. The question he asks is: ‘How did Monetarism capture the Conservatives?’ It is a genuine mystery, and also a very...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.