Hugh Lloyd-Jones

Hugh Lloyd-Jones is Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford University. His latest books, Blood for the Ghosts and Classical Survivals, will be reviewed here by M.I. Finley.

Homage to Scaliger

Hugh Lloyd-Jones, 17 May 1984

Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609) was a towering figure in the history of European scholarship. During the first half of his career, he virtually created the systematic study of early Latin; during the second, using Oriental as well as Greek and Latin sources, he laid the foundations of our knowledge of the chronology of the ancient world. Born and brought up at Agen in the west of France, he was the son of Julius Caesar Scaliger, a Latin scholar of distinction, who claimed to be descended from those Della Scalas who were lords of Verona during the Middle Ages. So far as he was able, the elder Scaliger gave his son a thorough training: but he greatly preferred Latin to Greek literature, and his Greek left much to be desired. His son reacted against his father’s anti-Hellenism: after his father’s death, at the age of 18, he made his way to Paris, where the famous Hellenists Turnebus and Auratus were active. With help from them and by his own strenuous efforts, he acquired a remarkable command of Greek, and went on to attain proficiency in Hebrew. By 1562, he had taken the fateful step of becoming a Calvinist. He obtained the patronage of Louis Chasteignier, lord of La Roche-Pozay near Poitiers, and in 1565 accompanied him on a diplomatic mission to Italy. Despite his Calvinistic contempt for Italian scholars and the Catholic Church – he preferred talking Hebrew with the learned Jews of Mantua and Ferrara to cultivating the society of Italian Humanists – he was inspired by the sight of Rome and the opportunity to copy inscriptions. Returning home in 1567, he found his studies interrupted by the religious wars of that and the following year. Making his way to Valence, in Dauphiné, he spent two years under the aegis of the great jurist Cujacius, who had an important influence upon his work. After the massacre of St Bartholomew in August 1572, he fled to Geneva, where he had contacts with other Protestant men of letters. Largely owing to the protection of the La Roche-Pozay family, he managed to carry on his work during the wars of the League. But in 1593, the year when Henri IV decided that Paris was worth a mass, he accepted the offer of a chair at the newly founded university of Leiden, which had already become one of the chief cultural centres of Europe. Here he taught such pupils as Daniel Heinsius and Grotius, and here he died in 1609.–

Modern Prejudice

2 December 1982

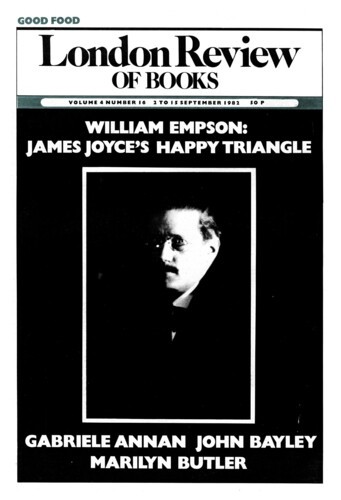

Homer’s Skill

Hugh Lloyd-Jones, 2 September 1982

The thorough understanding of a difficult text, even of one written in one’s own language, may be made far easier by a good commentary. Eliot himself provided, if not a commentary, useful notes upon The Waste Land, and an Oxford don, John Fuller, has written an excellent commentary on Auden’s poems. In the case of a text written in an ancient language, a commentary is particularly useful. The Greeks themselves had started to write commentaries on Greek poems as early as the fourth century BC. In the first place, a commentary on an ancient text must explain the meaning of the words. But a commentary need not be narrowly linguistic, like that expounded by the Victorian schoolmaster who began the term by saying to his sixth form, ‘Boys, you are about to enjoy the privilege of studying the Oedipus Coloneus of Sophocles, a veritable treasure-house of grammatical particularities’; neither need it concentrate narrowly on the establishment of the author’s correct text, like Housman’s famous commentary on the astrological poem of Manilius. Wilamowitz and other German scholars of the 19th century held that a good commentary should explain the subject-matter of the text it illustrates; its author will need to know history, archaeology and linguistics, as well as literature and language. A commentary should also pay attention to the author’s style, and here not all learned persons have been equally successful; it helps if the writer of the commentary has a style himself. The most learned commentary written in the English language on a Greek or Latin text, the commentary on Aeschylus’s Agamemnon written by the late Eduard Fraenkel, tries to fulfil all these requirements: but readers who are not professional scholars may well find it too exhaustive. The commentaries on the seven plays of Sophocles published during the last quarter of the 19th century by the Cambridge scholar, Sir Richard Jebb, had certain technical deficiencies, even when they were new, and the writer’s taste was naturally that of a man of his own time. But they are a singular, if not a unique, example of a commentary which is not only a work of learning but a literary study, and is itself a work of literary art.

Brennan’s Mentions

15 July 1982

Pieces about Hugh Lloyd-Jones in the LRB

Jesus Christie

Richard Wollheim, 3 October 1985

There are, I am sure, in the lives of all of us except perhaps the most low-spirited, some four or five people whom we cannot forgive. By this I do not mean anything necessarily moral. We...

Modern Prejudice

M.I. Finley, 2 December 1982

Of the 53 short essays, book reviews, lectures and obituaries assembled in Hugh Lloyd-Jones’s two volumes, two were published in the year before he assumed the Regius Professorship of Greek...

Tribute to Trevor-Roper

A.J.P. Taylor, 5 November 1981

The festschrift, a collection of essays in honour of a senior professor, used to be dismissed as a rather tiresome German habit. Now, I think, it has become embedded in English academic...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.