Plain girl’s revenge made flesh

Hilary Mantel, 23 April 1992

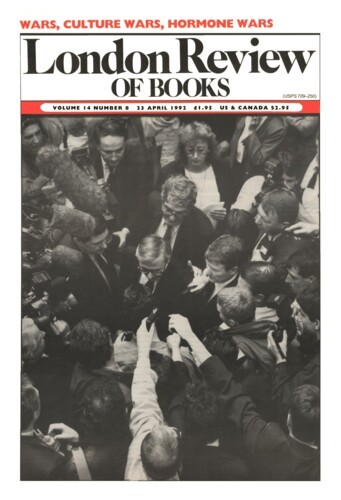

Christopher Andersen’s book begins, as it should, with the prodigal, the violent, the gross. But what do you expect? Madonna’s wedding was different from other people’s. The plans were made in secrecy, and backed by armed force. ‘Even the caterer … was kept in the dark until the last minute.’ You also, you may protest, have been to weddings where the caterer has seemed to be taken by surprise. But we are not talking here about a cock-up with the vol-au-vents. We are talking about something on the lines of Belshazzar’s feast: but more lavish, and more portentous.