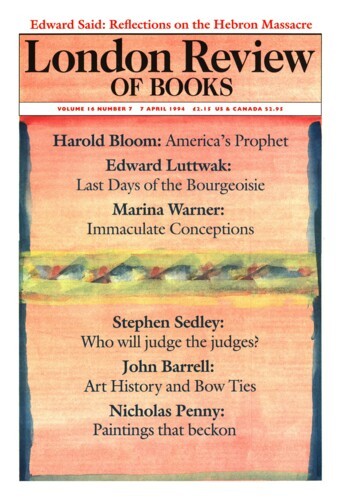

Grandfather Emerson

Harold Bloom, 7 April 1994

Richard Poirier, now in his middle sixties, seems to me perhaps the most eminent of our living literary critics, at least in the United States. He has a central position in contemporary American letters, as the editor of Raritan, the best of our quarterly reviews, and as the presiding spirit of the Library of America, the definitive publisher of the classic texts of the national literature. His own books chart much of the development in American criticism during the last three decades, from The Comic Sense of Henry James (1960) and A World Elsewhere (1966), through a middle phase in The Performing Self (1971) and Norman Mailer (1972), on to the major study of Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing (1977), and culminating in The Renewal of Literature: Emersonian Reflections (1987) and Poetry and Pragmatism (1992), now belatedly under review. More perhaps than anyone else, Poirier has led the fierce revival of Ralph Waldo Emerson that has proceeded from about 1965 to the present moment. Though I am going to lament Poirier’s drive to obscure the truth that Emerson essentially was a religious writer, akin to other gnostics ancient and modern, I begin by acknowledging a debt to the example of Richard Poirier. In a bad time he continues to represent what is strongest in his nation’s critical intelligence, and he yields nothing to mere fashion or to the ideology of the politicised academic rabblement. He is precisely what Emerson meant by ‘the American scholar’, the ‘single candle’ that might yet illuminate all men and all women.