Graham Hough

Graham Hough is the author of The Last Romantics.

Doomed

Graham Hough, 3 December 1981

It is a curious thing that while so many critics are busy telling each other that literature is a linguistic game, that novels are purely formal structures and that their pretensions to represent the world are illusory, novelists continue to write what in any serious sense must be considered historical novels. By a historical novel I mean, not period romance, but a fiction that is tied by close and numerous links to a real place at a real time, its essence being to tell a truth about an independently verifiable world, outside the realm of fiction. One of the most famous of these came out in 1948: it was Alan Paton’s Cry, the beloved country, so intimately bound up with South African history that Paton had to write a preface to distinguish those parts which are formally fiction. ‘As a social record,’ he concluded, ‘it is the plain and simple truth.’ Of course it is not merely a social record: it is the deeply imagined story of an individual life. And Paton has had to devise a language to tell the story in, for the simple Zulu parson who is the protagonist does not deal in the current coin of modern English speech. So that the literary question was as demanding as the historical one; the political act cannot be separated from the work of art. Now, after thirty years, comes Ah, but your land is beautiful, with similar themes and settings, the date of the action a few years later, the conflicts more distinctly those of the modern world. And though the continuity with Paton’s earlier work is complete, this is a different kind of book. Cry, the beloved country is an exploration both of the racial problem and of personal suffering; and its quasi-Biblical language is a means of penetrating into a sorrowful and bewildered consciousness. Ah, but your land is beautiful is a panorama, a chronicle, with a wide variety of characters and the interest distributed between them. It is a less lyrical and more political book, in part an evident roman-à-clef. The period is the 1950s, the time of the Passive Resistance campaign, the Sophiatown removals, the emergence of the South African Liberal Party and the early stages of the Nationalist government.

Chonkin’s Vicissitudes

Graham Hough, 1 October 1981

Vladimir Voinovich’s Pretender to the Throne is a continuation of The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin, and most of what has been said about the earlier book is equally true of this one. Equally untrue too. A comic novel about wartime Russia, a comic novel about Stalinism, is on the face of it such a contradiction in terms that the attempt to describe it keeps tripping up on misleading descriptions and false analogies. It is not, as has been said, a kind of Russian surrealism, for it does not revel in the irrational: the fantasy is all an extravagant blow-up of quite actual situations. It is not a Russian Catch-22, for the savage comedy of Catch-22 undermines all values: the only response left to absurdity and horror is a flat nihilism. Chonkin’s adventures take place in a world of tyranny, treachery, hypocrisy and cowardice: yet the possibility of another way of life is never really forgotten. The obvious ancestor is Gogol: the scarifying satire in which nevertheless the human points of reference are not lost is close to Dead Souls and The Government Inspector. The setting is the same – the god-forsaken provincial hole sunk fathoms deep in bureaucracy, stupidity and corruption. Of course, the political conditions are more frightful than anything in Gogol’s world, and the Germans are at the gates; but in reading Chonkin we often forget that it is 1941; we seem to be back in one of those timeless 19th-century Russian fictions. And indeed we are not very firmly in 1941. For all the wartime setting, the workings of the Party juggernaut portrayed here seem to embody the spirit of the whole Stalin era, seen presumably (we are not told when the book was written) from some point during the brief post-Stalin thaw.

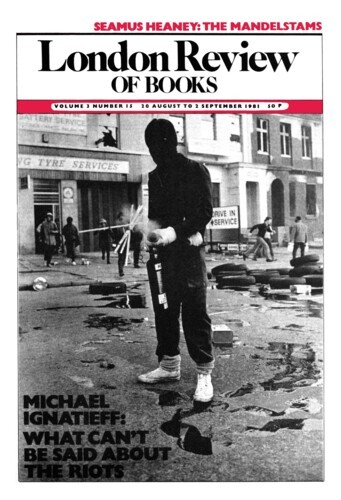

Structuralist Methods

20 August 1981

Sacred Monster

Graham Hough, 20 August 1981

For readers who are more interested in literature than in literary society those sacred monsters who live in anecdote and legend rather than in their work are always something of an embarrassment.

Pieces about Graham Hough in the LRB

Yeats and the Occult

Seamus Deane, 18 October 1984

The first three of the four chapters in Graham Hough’s book were the Lord Northcliffe Lectures in Literature given at University College London in February 1983. The audience was general...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.