Bloomsbury on the left, Neo-Pagans on the right, these columns represent, more or less, Paul Delany’s relative definition of the two Edwardian intellectual groups. The first two pairs of adjectives are quoted from his Introduction. Of course, Bloomsbury and the Neo-Pagans had much in common: an educated upper middle-class background; Cambridge – almost all the men went there, and some of the women; at Cambridge, the Bloomsbury men mostly belonged to the Apostles, and so did Rupert Brooke and Ferenc Bekassy, a fringe Neo-Pagan; nervous breakdowns were common in both groups and treated by the same doctors with the same regime – called ‘stuffing’ – in the sense of fattening up; members of both sets recognised one another in the audience at the opera and Diaghilev’s London seasons. If they did not all know one another, at least they knew of one another – in l911, there was a partial, temporary and gingerly link-up, initiated by Virginia Woolf; and all along James Strachey, born to be Bloomsbury but in love with Rupert Brooke, functioned as a sort of inter-coterie courier.’

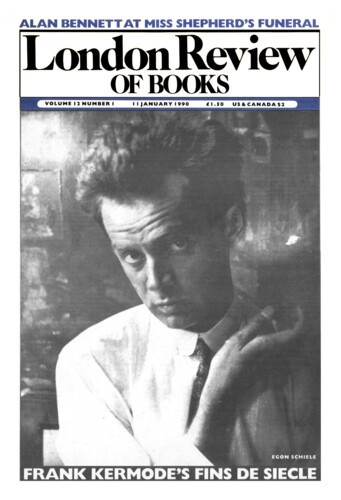

The Neo-Pagans: Friendship and Love in the Rupert Brooke Circle by Paul Delany. Bloomsbury on the left, Neo-Pagans on the right, these columns represent, more or less, Paul Delany’s relative definition of the two Edwardian intellectual groups. The first two pairs of...