Poem: ‘A Letter to Wystan Auden, from Iceland’

Francis Spufford, 21 February 1991

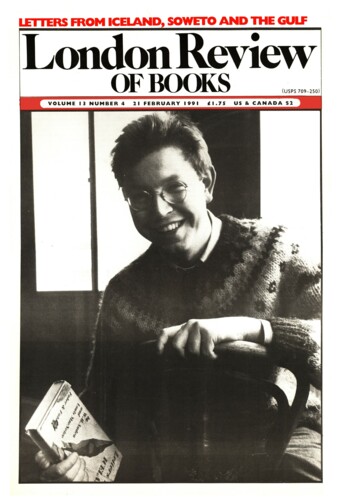

for the maker of ceramic pots

IDear Wystan Auden, as I lay last night Unsleeping on a hard Youth Hostel bed, The windows pearly with the pale twilight That glows on constantly up here instead Of proper dark, a thought traversed my head: How fine if I could summon down from heaven The flax-haired you of Nineteen...