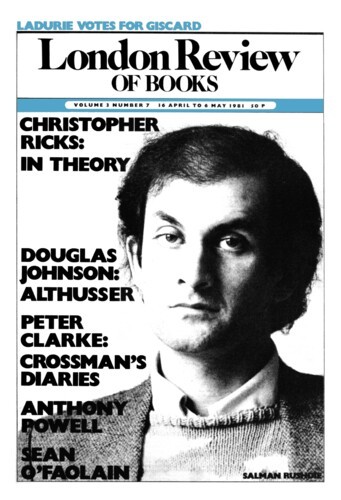

It is now seven months since the Socialists came to power in France – time enough for us to draw up an end-of-year or new year balance of their achievement. President Mitterrand, like Mendès-France, was long a staunch opponent of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, but, despite this, he has had no trouble in adapting to the institutions bequeathed to him by de Gaulle. In terms of ceremonial, he has abolished some needlessly regal customs brought in by his predecessor – having himself served first at table or taking precedence on entering a room; and he has avoided over-exposure on television. But he respects the undoubtedly monarchical, or at least personalised spirit of our institutions. These words are not intended to be derogatory: as a historian of the 18th century, I am more aware than most of the benefits which may be derived from monarchical or semi-monarchical structures, provided they are enlightened – and there is no doubt that our President is a man of culture. Nonetheless, the concept of a ‘personalised regime’ remains in itself inadequate to construe the situation in France. Giscard was, to some extent and without seeking to be so, a one-man show. He has been criticised for colonising the state through his supporters, but this process could not be carried beyond a certain point because the former President did not stand at the head of a major political party: he had relatively few ‘clients’ at his disposal. He attracted the support of a first-rate bureaucratic élite (men like Brossolette, Cannac and Verdeil): but he did not a priori advance liegemen whom he had brought up from nothing.

It is now seven months since the Socialists came to power in France – time enough for us to draw up an end-of-year or new year balance of their achievement. President Mitterrand, like...