Elisa Segrave

Elisa Segrave’s first book, Diary of a Breast, will be reviewed here by Mary Beard.

Diary: Is this what it’s like to be famous?

Elisa Segrave, 11 May 1995

My first book is now published. It’s a tragi-comedy about breast cancer. I’ve just got back from America, where I was carrying copies of it around in a beach-bag, trying to sell it to a New York publisher. In the Random House building, there were over twenty elevators, and a publisher on almost every floor. I ricocheted up and down, darting into offices without appointments, leaving my book like a cuckoo laying eggs. In one office a friendly black receptionist gave me a copy of Caroline Blackwood’s account of the Duchess of Windsor and her French lawyer, Maître Blum. The girl dismissed my interest in a history of the Harlem Renaissance, repeating how much she loved the book on the Duchess. I read it all night on the plane back, every now and then bursting out laughing.

Paulie lops it off

Elisa Segrave, 2 December 1993

I met Susan Swan, the author of this novel about a girls’ boarding-school, in a women’s dormitory on a holistic holiday in Greece. Apart from Susan, there was Tessa, a potter from Brixton, a German called Ingrid and Marjorie, an aromatherapist from Liverpool. Susan was a cut above the rest of us. She had been invited as a teacher of creative writing and had then been given the special status of literary consultant. While the other teachers taught mime, self-healing, massage, Tai-Chi and wind-surfing in groups, beginning at 7 a.m., Susan saw aspiring writers one at a time in the café on the beach, where she sat in a stately way sipping Greek coffee. She seemed to have thought deeply about writing, how it related to one’s life, and about the relations between men and women. She quickly assumed the role of big sister, school prefect, or even the witch, the one with magic powers. I had two sessions with her: she showed me a way of analysing dreams; and, as women often do, we discussed the opposite sex.

Diary: Revved Up on Solpadeine

Elisa Segrave, 22 July 1993

Saturday. I’m in a ward in the Charing Cross Hospital with Bertha, another woman with breast cancer. All the lymph glands under my right arm have been removed. Bertha, who’s 60 and lives near Heathrow Airport, is talking to a woman with hennaed hair who was bitten by her own corgi, or her daughter’s corgi, I’m not sure which. The corgis are father and son. The son attacked the father and they fought viciously till the corgi’s father’s owner, the woman talking to Bertha, managed to force a hoover down one dog’s throat. She then shut one dog in the garage but the other one bit her in the wrist. Her wrist is poisoned and she has to stay in hospital Several extra days.

Remembering Janet Hobhouse

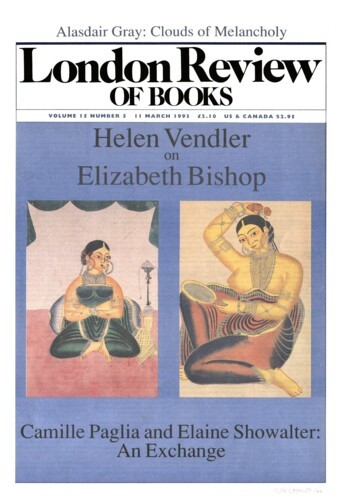

Elisa Segrave, 11 March 1993

Janet Hobhouse, whom I first met in a street in Paris in 1974, was someone who inspired strong emotions. Being with her was like being on a roller-coaster, an exhilarating, intense, even frightening experience – a roller-coaster you often wanted to get off.

Pieces about Elisa Segrave in the LRB

‘Cancer Girl’

Mary Beard, 6 July 1995

Cancer must sell almost as many books as cookery: not just old-fashioned self-help guides to detection or prevention, tips on how to survive the chemotherapy or colostomy (now lavishly...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.