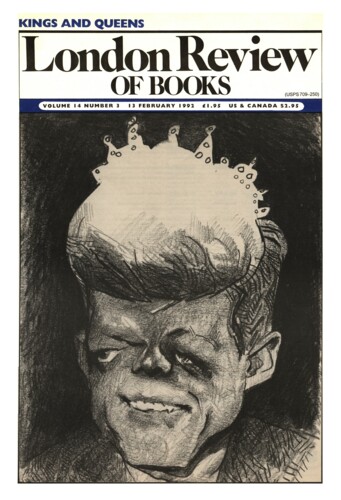

Something to Do

David Cannadine, 23 September 1993

Few reputations are so fragile or ephemeral as those of minor modern royalty – the brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, younger sons and daughters, cousins and more distant relatives of big daddy and the queen bee. By birth and by definition, they are lifelong occupants of the substitutes’ bench, permanent understudies for the starring roles which rarely if ever come their way, too near the throne to be ordinary people, too far removed to be right royally important. For the most part, their lives are a bizarre and unhappy amalgam of cosseted privilege, unostentatious dutifulness, peripheral appeal, honorific marginality, wearying ceremonial, resentful disappointment, embittered loneliness and – if they are lucky – occasional scandal. In death the best they can hope for is to be instantly forgotten, with no realistic prospect of later rediscovery. Who, today, knows anything about such defunct dynasts as the Duke of Cambridge, the Marquess of Carisbrooke or the Earl of Athlone?’