Colin McGinn

Colin McGinn a reader in philosophy at University College London, is soon to take up the position of Wilde Reader in Mental Philosophy at Oxford. He is the author of Wittgenstein on Meaning.

Imagining an orgasm

Colin McGinn, 9 May 1991

The more philosophically interesting a science, the less secure or transparent are apt to be its theoretical foundations, given that philosophy thrives on perplexity. It is some time since chemistry produced much of a reaction in philosophers, but biology can still get their juices flowing, though not so freely as in the days of the Bergsonian élan vital. Quantum physics is a contemporary focus of philosophical attention – despite the suspicion of some that it is only a dispensable anti-realism that generates the putative puzzles. Mathematics induces periodic bouts of fascination, even of deep distrust – as with Brouwer and Wittgenstein – but its rigour and finality tend to keep the perplexities at bay. In the case of psychology, however, philosophical interest reaches its highest pitch, and never more so than at present: perhaps to the chagrin of practising psychologists, philosophers are now very interested in what they are doing – or at any rate in what they ought to be doing.

Eating animals is wrong

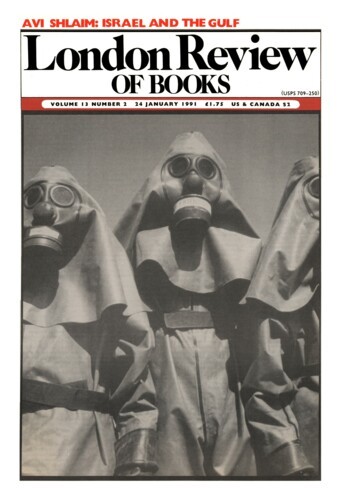

Colin McGinn, 24 January 1991

I have been persuaded of the rightness of the moral position advocated in Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation for the past twenty years. There is, in my view, no moral justification whatever for the human exploitation of animals. I was convinced of this principally by reading the path-breaking book, Animals Men and Morals (1971), edited by Stanley and Roslind Godlovitch and John Harris. Singer acknowledges his debt to this pivotal work as well as to personal contact with some of the contributors, and his own 1975 book, of which there is now a welcome second edition, is largely a sustained working-out of the moral perspective developed by these earlier thinkers. I have to declare that, in my opinion, the arguments Singer mounts, and the facts he marshals, constitute a definitive and unanswerable case for the thesis that our treatment of animals, in every department, is deeply and systematically immoral. Becoming a vegetarian is only the most minimal ethical response to the magnitude of the evil. What is needed is a complete revolution in the way we deal with other species. Do not expect, then, to find me in any way ‘balanced’ on the question: this is not really an issue on which there are two sides. It’s a won argument, as far as I’m concerned – in principle if not in practice.’

Badoompa

10 January 1991

My Wicked Heart

Colin McGinn, 22 November 1990

Was Wittgenstein a spiritual as well as a philosophical genius? Ray Monk’s exceptionally fine and fat biography puts us in a better position to answer this question than we have been hitherto.

Pieces about Colin McGinn in the LRB

Avoiding Colin

Frank Kermode, 6 August 1992

Once there were popular books with titles like Straight and Crooked Thinking, books in which professional philosophers, avoiding arcane speculation, tried to make the rest of us more sensible by...

Too hard for our kind of mind?

Jerry Fodor, 27 June 1991

Whatever, you may be wondering, became of the mind-body problem? This new collection of Colin McGinn’s philosophical papers is as good a place to find out as any I know of. Published over a...

Putnam’s Change of Mind

Ian Hacking, 4 May 1989

Big issues and little issues: among established working philosophers there is none more gifted at making us think anew about both than Hilary Putnam. His latest book is motivated by large...

An End to Anxiety

Barry Stroud, 18 July 1985

Wittgenstein predicted that his work would not be properly understood and appreciated. He said it was written in a different spirit from that of the main stream of European and American...

Persons

Brian O’Shaughnessy, 1 April 1983

The philosophy of mind is a branch of the philosophy of nature. But it has this peculiarity, that the very item that conjures up its questions and vets its answers is the very part of nature...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.