Christopher Ricks

Christopher Ricks is the author of Keats and Embarrassment, among other books. He is a professor of English at Cambridge University.

Version of Pastoral

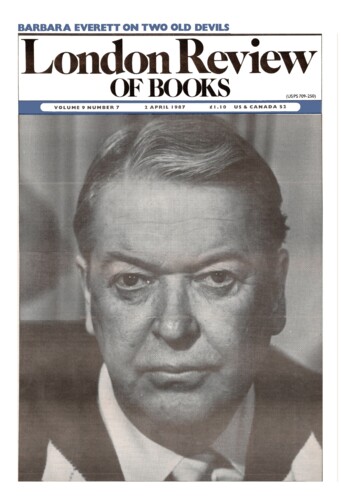

Christopher Ricks, 2 April 1987

The Enigma of Arrival: V.S. Naipaul’s title is the one at which Apollinaire enigmatically arrived, for the painting by Giorgio de Chirico. A detail of it illuminates Naipaul’s cover and his book: making their huddled way from a classical quayside (the scene bathed both in shadow and in sun), two stoled figures have their obscured faces towards us and their backs to a wall. Above the wall billows the sunlit summit of a sail.

Lyrics and Ironies

Christopher Ricks, 4 December 1986

Faintly repelled by elaborate theories of irony and by taxonomies of it, D.J. Enright has set himself to muster instances, observations, localities and anecdotes. There is no continuing argument, and not much argufying even, but there are plenty of penetrating glances. ‘Rather than theory, it is something resembling “practical criticism” that this book will concern itself with: the exploration of individual ironies as they are manifest in life as well as in literature.’ This is good-naturedly loose, the recipe for something resembling a scrapbook, a scrappy one. ‘When I was making notes for this book I came, before long, to see irony everywhere.’ Likewise when you were making a book for these notes.

Death for Elsie

Christopher Ricks, 7 August 1986

Patricia Highsmith has been praised by Graham Greene in the good old way as ‘a writer who has created a world of her own’. She can be even better than that – when she takes a world and makes it not only her own but ours. She lurks in the murk where you have to peer to check if this is an – or the – underworld. In her seething city-settings, paranoia may be the saving of you, and yet paranoia does have, too, a hideously masochistic alluring power. She is the poet of these death-bearing pheromones of fear.’

For good or bad

Christopher Ricks, 19 December 1985

Geoffrey Hartman’s Easy Pieces can be hard going. ‘To see, oneself unseen, as at the movies, is only less than the ecstasy of an unseeing seeing: of going beyond the non-language of images to the non-language of non-images, or a glance that is not guilty, that is both knowing and pure.’ This is not incomprehensible, but it is not by any stretch easy either, and it tips a glance that is guilty. It invites the mild dismay of a poet to whom Hartman is prudently indifferent, Byron: ‘I wish he would explain his explanation.’ Yet it was Coleridge whom Byron was scorning there, and Hartman would not mind being tarred with the same brush as so myriad-minded a critic. But then again Coleridge didn’t go in for ingratiations, for titles like Easy Pieces, an act of calculated charm not compatible with the essential (in its essence) charmlessness which has to end an essay like this: ‘Even philosophy’s insistence on clear and distinct ideas may express this “ineluctable modality” of the perceptible that makes what we call representation the unexcludable middle between phenomenal reality and mind, between thinking in images and thinking by means of texts against them.’ This is a dour culmination, and it is a pity that Hartman’s sense of himself and of his enterprise will not entirely countenance honest dourness even of his own choosing – which is why he has to insinuate the easy piece ‘what we call representation’. What does it actually what we call mean to say ‘what we call representation’? This is manoeuvring, ‘I could an I would’, both knowing and impure: ‘propitiation’s claw’. For these pieces, like so much of recent Hartman, and unlike his large upright book on Wordsworth, are not easy but uneasy.’

Pieces about Christopher Ricks in the LRB

Saturday Reviler: Fitzjames Stephen's Reviews

Stefan Collini, 12 September 2024

What really distinguished the Saturday Review was its tone – self-consciously unillusioned, unsentimental, exacting, a tone that announced the presence of high-quality butchers specialising in the...

Ti tum ti tum ti tum: Chic Sport Shirker

Colin Burrow, 7 October 2021

If one suspects, at times, that one’s eye is being led on a dance, it is at least always a merry one, and Christopher Ricks is a fine enough critic to worry whether he might have crossed the invisible...

I gotta use words: Eliot speaks in tongues

Mark Ford, 11 August 2016

T.S. Eliot’s mind was a vast, labyrinthine echo chamber, and perhaps more than any other canonical poet of the English language he was conscious of the previous uses by other writers of the words he...

Misgivings: Christopher Ricks

Adam Phillips, 22 July 2010

In his first book, Milton’s Grand Style, Christopher Ricks showed us that Milton wanted his readers to be attentive to the fact that when our ‘first parents’ fell, their...

Forget the Dylai Lama: Bob Dylan

Thomas Jones, 6 November 2003

A scene from a concert: on stage, a young Jewish-American folk singer/ songwriter, accompanied only by his own guitar and the harmonica around his neck, with a forceful, nasal voice and...

Poisonous Frogs: Allusion v. Influence

Laura Quinney, 8 May 2003

This book comes in two parts. The first, ‘The Poet as Heir’, investigates characteristic uses of allusion by major British poets of the 18th and 19th centuries: Dryden, Pope,...

Elegant Extracts: anthologies

Leah Price, 3 February 2000

Anthologies attract good haters. In the 1790s, the reformer Hannah More blamed their editors for the decay of morals: to let people assume that you had read the entire work from which an...

Writhing and Crawling and Leaping and Darting and Flattening and Stretching

Helen Vendler, 31 October 1996

When Emerson wrote to Whitman that there must have been ‘a long foreground’ preceding the composition of Leaves of Grass, he expressed the curiosity every reader feels when coming upon...

The Verity of Verity

Marilyn Butler, 1 August 1996

Christopher Ricks’s new book makes available many of his distinguished lectures given in the Eighties and Nineties. The essays retain a sense of occasion, and of a star performance on...

Leases of Lifelessness

Denis Donoghue, 7 October 1993

Near to death in Malone Dies, Malone says: ‘I wonder what my last words will be, written, the others do not endure, but vanish, into thin air.’ Beckett’s Dying Words is not a...

Good enough for Jesus

Charlotte Brewer, 25 January 1990

The second edition of The State of the Language, published ten years on from the first, contains 53 essays and nine poems, each by a different author. The dust-jackets of both editions are almost...

Negative Capability

Dan Jacobson, 24 November 1988

T.S. Eliot and Prejudice. Keats and Embarrassment. The parallel between the title of Christopher Ricks’s new book and that of his earlier study of Keats is not accidental. In each case he...

Spruce

John Bayley, 2 June 1988

On 9 May 1933, A.E. Housman, Professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, and a scholar worshipped and hated for his meticulous standards and his appalling sarcasms on the unscholarly,...

Tennyson’s Text

Danny Karlin, 12 November 1987

Writing in 1842 to his friend Alfred Domett, who had emigrated to New Zealand, Robert Browning enclosed ‘Tennyson’s new vol. and, alas, the old with it – that is what he calls...

Beddoes’ Best Thing

C.H. Sisson, 20 September 1984

‘This is,’ as Professor Ricks says, in his rather baroque manner, ‘a gathering of essays, not a march of chapters’; each essay ‘attends to an aspect, feature, or...

English Changing

Frank Kermode, 7 February 1980

That language changes, and that we cannot prevent it from doing so, is a fact known to all, though some of us can no more contemplate it with resignation than we can death and taxes. It is two...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.