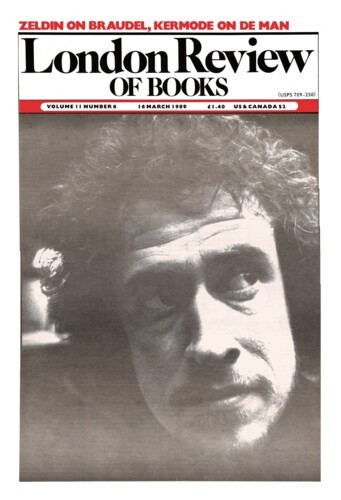

While Baudelaire, speech-bereft, lay on his sick-bed in Brussels, his mother, rummaging through his overcoat, came across some photographs of her son taken by Nadar. It was a strange but instructive find. Baudelaire detested photography (as a mere technology of mechanical reproduction, it was the emblem of modernity’s threat to art), and yet his own photographic image, notably the portraits left by Nadar, is in many ways a capital document for understanding the tormented, self-destructive trajectory of his ‘life’. Gaëtan Picon remarked that in the Nadar photograph of 1862 the 41-year-old Baudelaire looked as if he were a hundred (Baudelaire himself, in one of the ‘Spleen’ poems, made it a thousand). The face, above all the eyes with their look at once haunted and hunted, confirm the sentiment of overwhelming weariness expressed two years previously in a letter to his mother: ‘Oh how weary I am, how weary I’ve been for many years already, of this need to live twenty-four hours every day!’ He also wrote to his mother, in ghostly retrospect, as if he were the true author of the Mémoires d’ outre-tombe: ‘I gaze back over all the dead years, the horrible dead years.’ The photograph, too, suggests something of the ghost, akin to the spectral presences-absences that populate the street poems in the ‘Tableaux parisiens’ section of Les Fleurs du mal (the title for the collection as a whole was originally to have been Les Limbes).

While Baudelaire, speech-bereft, lay on his sick-bed in Brussels, his mother, rummaging through his overcoat, came across some photographs of her son taken by Nadar. It was a strange but...