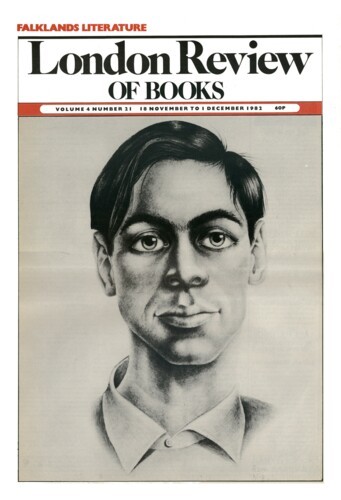

The Great Percy

C.H. Sisson, 18 November 1982

It is perhaps unkind to disturb the ashes of C. P. Snow. They have so recently been placed in the Fellows’ Garden at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he is commemorated beside John Milton. There is occasion to take a look at them, nonetheless, for we now have this account of the man by his brother, Philip Snow. ‘Brothers seldom write about each other,’ as the publisher says, and one may think that in general they are wise not to do so. C. P. Snow, however, knew that Philip would write this book ‘and welcomed it; his only stipulation was that it should not be published in his lifetime.’ There was ten years’ difference between the two men. C.P., who died in 1980, was born in 1905: Philip, who is still with us, in 1915. The portraitist says, rather oddly, that he cannot be said to have known his brother until he was about seven and his subject 17; as they were both living in the same house, with stable parents, he must mean that such knowledge could begin only with the age of reason. From then on, ‘the only prolonged period of separation was the war and its immediate aftermath.’ For those years he has drawn largely on correspondence, which makes this part of the book among the most illuminating. Philip regards C.P. as ‘the main influence’ in his life, and the admirer is as much in evidence as the brother.