Amit Chaudhuri

Amit Chaudhuri is a professor of creative writing at Ashoka University. He has written seven novels, most recently Friend of My Youth, and is a singer and composer.

Parsi Magic

Amit Chaudhuri, 4 April 1991

The Parsis of Bombay are pale, sometimes hunched, but always with long noses. They have a posthumous look which is contradicted by an earthiness that makes them use local expletives from a very early age; and a bad temper which one takes to be the result of the incestuous intermarriages of a small community. The Parsi boys in my class had legendary Persian names like Jehangir and Kaikobad and Khusro. Their surnames, however, can be faintly ridiculous in their eloquence, like ‘Sodabottleopenerwalla’.

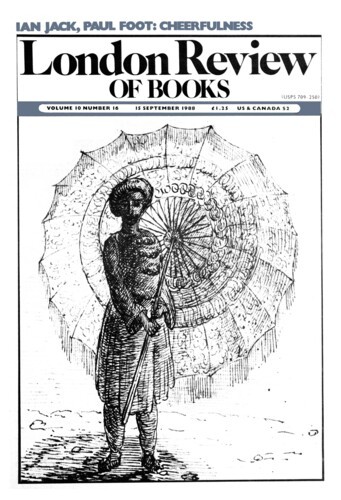

Other Eden

Amit Chaudhuri, 15 September 1988

There is something mildly disturbing about the way writers generalise about India. How do they do it, with a country so confusingly diverse in detail? Even the titles of some books – Heat and Dust, for instance – are generalisations. This book, Fanny Eden’s travel journals, wears its title like an uneasy crown: Tigers, Durbars and Kings suggests lazy stereotypes rather than particulars observed by someone alive to their surroundings. The suspicion proves to be ill-founded, however. What the blurb promises – ‘shrewd irony’, ‘perceptiveness,’ ‘immediacy’ – turns out, surprisingly, to be true. It is surprising because few books about India are really interested in India. The temptation to treat the country, with its elephants and tigers and idols, as a kind of enormous Disneyland for the Western mind, or as a vast trampoline for Western leaps into the obscure and the mystical – such temptations prevent many writers from ever really looking at the country. When one does look, as Fanny Eden does, the only honest initial response may be of puzzlement, a puzzlement which, if expressed wittily and intelligently, as it is here, can be more illuminating than certainties and absolute conclusions.’

Story: ‘Sunday’

Amit Chaudhuri, 5 May 1988

On Sundays, the streets of Calcutta were vacant and quiet, and the shops and offices closed, looking mysterious and even a little beautiful with their doors and windows shut, such shabby, reposeful doors and windows, the large signs – DATTA BROS., K. SINGH AND SONS – reflecting the sunlight. The house would reverberate with familiar voices. Sandeep’s uncle, whom he called Chhotomama (which meant ‘Junior Uncle’), was at home. Chhordimoni, Sandeep’s greataunt, and Shonamana, his eldest uncle, had also decided to spend the day here. If you overheard them from a distance – Sandeep’s uncle, his mother, his aunt, Chhordimoni and Shonamama, all managing to speak at the top of their voices without ever making a moment of sense – you would think they were having a violent brawl, or quarrelling vehemently about the inheritance of some tract of land which they were not prepared to share. And, indeed, they were engaged in an endless argument (about what, they did not know) beneath which ran a glowing undercurrent of agreement in which they silently said ‘yes’ to each other.’

Poem: ‘St Cyril Road, Bombay’

Amit Chaudhuri, 25 June 1987

Every city has its minority, with its ironical, tiny village fortressed against the barbarians, the giant ransacks and the pillage of the larger faith. In England, for instance, the ‘Asians’ cling to their ways as they never do in their own land. On the other hand, the Englishman strays from his time-worn English beliefs. Go to an ‘Asian’ street in London, and you will...

Pieces about Amit Chaudhuri in the LRB

Chairs look at me: ‘Sojourn’

Alex Harvey, 30 November 2023

Amit Chaudhuri’s Sojourn is interested in our relationship to the history we are living through, conscious that no one is fully aware of living in an historical epoch, perhaps as fictional figures can’t...

Never Not Slightly Comical: Amit Chaudhuri

Thomas Jones, 2 July 2015

The meanings that the word abroad has accumulated since it was first used to mean ‘widely scattered’ include: ‘out of one’s house’ (Middle English), ‘out of...

At Ramayan Shah’s Hotel: Calcutta

Deborah Baker, 23 May 2013

In January 1990 I moved from New York to Calcutta to get married. Having never been to India, I came equipped with V.S. Naipaul’s India: A Wounded Civilisation and Geoffrey...

Can’t it be me? Amit Chaudhuri’s new novel

Glyn Maxwell, 9 April 2009

There’s nothing like a book about music to remind the reader of the silence. Nothing else insists so emphatically on what we are usually happy to forget: that, during the hours we read, our...

Anti-Humanism: Lawrence Sanitised

Terry Eagleton, 5 February 2004

One of the most tenacious of all academic myths is that literary theorists don’t go in for close reading. Whereas non-theoretical critics are faithful to the words on the page, theorists...

Handfuls of Dust: Amit Chaudhuri

Richard Cronin, 12 November 1998

The first of the great Indian novelists to write in English, R.K. Narayan, wrote modest novels about modest people living in the small South Indian town of Malgudi. The completeness of the world...

Doing justice to the mess

Jonathan Coe, 19 August 1993

The triumphs of this novel are at once tiny and enormous. Tiny because, like its predecessor A Strange and Sublime Address, it tells only of a placid and uneventful life, a life of domesticity,...

City of Dust

Julian Symons, 25 July 1991

What Carlyle called the Condition of England Question – in our day, the country created by Thatcher and her sub-lieutenants – is surely the ripest subject on offer to novelists. The...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.