‘How life is in there’

Selma Dabbagh

The British brought the system of administrative detention to Palestine when they were the mandatory power. According to Article 111 of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945, ‘a military commander may by order direct that any person shall be detained in such place of detention as may be specified by the military commander in the order.’ The rules also authorised military courts, restriction of movement, censorship, the expropriation and demolition of houses, arbitrary searches and curfews, and were used by the British against both Palestinians and immigrants of Jewish and other religious backgrounds.

Despite many of its founders being caught on the wrong side of these laws, Israel adopted them in 1948 and has strenuously resisted attempts to modify their provisions. In December 2022 there were 791 Palestinians in administrative detention in Israel. By December 2024 the number had increased more than fourfold to 3327 – over a third of the nearly ten thousand Palestinians being held prisoner by Israel on security grounds.

Three hundred of them are children. In 2016 Israel introduced a law allowing children between the ages of 12 and 14 to be held criminally responsible. This was after Ahmed Manasra had been arrested at the age of 13 in East Jerusalem. Israel was already the only country that routinely tries children in military courts. An estimated ten thousand Palestinian children have been held in Israeli military detention – where, in the words of Save the Children, they are ‘stripped, beaten and blindfolded’.

Nasser Abu Srour was in his early twenties when he was arrested in 1993 for his part in the first Intifada (1987-92) and sentenced to life in prison. In The Tale of a Wall, published last year in Luke Leafgren’s English translation, Abu Srour describes being moved from prison to prison, from cell to cell, and seeking out in each space a point of contact with the wall that encloses him:

This is not my story … This is the story of a wall that somehow chose me as the witness to what it said and did. The sentences of this text could not have been composed without the support of that single, solid source: the wall.

In his novel The Trinity of Fundamentals, also published last year in Muhammad Tutunji’s English translation, Wisam Rafeedi gives thanks in the acknowledgments to ‘three splendid comrades, ‘Omar Tayeh, Yousef al-‘Ati, and Yousef ‘Abdul-‘Al at Al-Nafha Prison, who took upon themselves the laborious tedious task of copying this novel on fifty-four capsules and arranging to smuggle them through six prisons and delivering them safely into my hands.’ A footnote explains that he is referring to ‘a method used by the Palestinian prisoners’ movement to fold and wrap paper into the size of medicine capsules in order to transfer information’.

In the film 3000 Nights (2015), Mai Masri dramatises the experience of a newly married schoolteacher in the West Bank who is sentenced to eight years in prison by an Israeli military court for giving a lift to a young man. Unaware that she is pregnant at the time of her arrest, she is shackled to a bed when giving birth in prison.

In 2021, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention criticised Israel for its treatment of three female students from Birzeit University in the West Bank. The authorities used ‘excessive force’ and denied the young women access to a lawyer. ‘The failure to remove handcuffs when eating, the imposed use of a toilet without a door for privacy and the failure to provide appropriate clothing, reveal a prima facie breach of the Bangkok Rules’ on the treatment of women prisoners.

Layan Kayed, Ruba Asi and Elyaa Abu Hijla are more photogenic than the men whose images have appeared on social media in recent weeks, bound or chained, naked or stripped to their underpants. Some of the men’s bodies look bruised and burnt; others have numbers spraypainted on their backs. One comment asks for the men’s genitals to be obscured ‘for their dignity’. Al Jazeera reports that 14,500 Palestinians have been arrested since October 2023 in the West Bank (some since released), with uncountable ‘thousands’ arrested from Gaza. The testimony of those who have been released indicates that their treatment has never been so brutal.

On 26 February, the Empire State Building shone orange to honour the memory of Shiri, Ariel and Kfir Bibas, who died when taken hostage in Gaza. The Bibas family refused to allow Netanyahu or any Israeli government representatives to attend the funeral of their loved ones. ‘If they put lights every night for each child killed in Gaza,’ Assal Rad wrote on Instagram, ‘it would take 48 years.’

Seventeen-year-old Muhammad Abu Sahloul was released on 26 February after 13 months in Israeli detention. He said he had no idea he was about to be released, but thought he would be in there for ever, and ‘never see the sky without bars again’. ‘What can I even tell you? How can I explain?’ he said. ‘I have seen so much I can’t even explain how life is in there. They let the dog urinate upon you, they do so many things. You could be sleeping standing just as you are and they pick you up and slam you to the floor. Two, sometimes three of them at once. Torture with electricity, pulling your hair.’

Sixty-year-old Diaa al-Agha was released after 33 years. Too weak to walk, he had to be carried to his mother. Doctor Khaled al-Ser, who was abducted from Nasser Hospital seven months ago, said that to talk about the brutality of the soldiers at Sde Teiman detention camp would take him ‘more than one day, two days’. As a doctor, he heard medical testimony from other inmates, who had been ‘sexually assaulted by the soldiers using batons and sometimes using electrical guns, tasers, in their sensitive areas’. He went on to describe mock trials and other forms of psychological torture.

Marwan Barghouti has been imprisoned since 2002. He has won elections while behind bars. The separation wall near the Qalandiya checkpoint out of Ramallah is dominated by a graffiti image of his face. There are hopes for his release in the current exchanges of captives, but Israel may be reluctant to let out a man who has often been compared with Nelson Mandela.

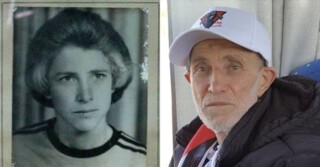

Dr Mustafa Barghouti (a distant cousin) is head of the Palestinian Medical Relief Society. On 28 February, he posted two images of another relative, Nael Barghouti, ‘the longest incarcerated political prisoner in the world’, who was ‘released from Israeli prison last night after a long delay and has been deported to Egypt. His wife, who lives in Ramallah, was prevented from going to Egypt to meet him by the Israeli authorities.’ The photographs show Nael before he was imprisoned and now.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Israel has arrested seventy journalists and media workers since October 2023, of whom 34 remain in detention. This is on top of the more than 170 journalists who have been killed. As Reporters without Borders put it last September, ‘at the rate journalists are being killed in Gaza, there will soon be no one left to keep you informed.’

Information on raids by the Israeli army since it declared its ‘Operation Iron Wall’ against the occupied West Bank on 21 January, two days after the temporary ceasefire in Gaza, is sparse. With attacks on the governorates of Jenin, Tubas, Tulkarem, Nablus, Hebron, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Qalqiliya and Jericho, an estimated forty thousand people have been displaced. Several densely populated refugee camps are said to have been emptied. Families are given only a couple of hours to leave their homes. There is nowhere for them to go. At the British Library on 3 March, Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson spoke of the generosity of the people providing food and shelter to those fleeing. With the raids come more arrests.

As Israel refuses to withdraw from the Gaza-Egypt border, threatening negotiations, Netanyahu, on the second day of Ramadan, declared a total block on humanitarian aid to the Gaza Strip. Recent reports by Forensic Architecture show evidence of Israel’s ecocide in Gaza, including the systematic targeting of agricultural land and infrastructure. It has been over a year since human rights groups reported that Israel was using starvation as a weapon of war. Even with the relative trickles of aid entering Gaza in October 2024, the UN was reporting on an ‘intolerable’ situation with ‘extremely critical levels of hunger’, and famine looming.