In Gaza Nothing’s Impossible

Selma Dabbagh

‘Can you believe this has been going on for six hundred days?’ one of my fellow panellists asked the audience at Reference Point on Saturday, 24 May. We’d just watched Garry Keane and Andrew McConnell’s documentary Gaza, filmed between 2014 and 2018. The surgeon Khaled Dawas said: ‘The opening music gets me every time.’ The hospital where he has worked in Gaza was recently bombed. Aser el Saqqa, whose family’s cultural centre in a restored Ottoman palace was destroyed, said it would have been good if the film had shown more of the ancient souks, the Omari Mosque, St Porphyrius Church, the rich history of Gaza going back to the Canaanites.

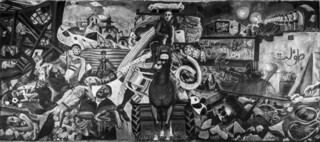

Malak Mattar’s monumental 2024 black-and-white painting inspired by Guernica is entitled No Words (… for Gaza). A photographer told me he has aerial images taken in May 2023, October 2023 and May 2025 which say it all. On Sunday, 25 May, I went to see Bashar Murkus’s Milk performed by Khashabi Theatre at the Southbank Centre and wept throughout. A performance told in milk, blood, movement: some things are incommunicable through words. But words are all that some of us have.

‘It is important that you write,’ my friend Dr Atef Alshaer told me earlier in the month, at the launch for Ghada Karmi’s new book, Murjana, a novel set in ninth-century Baghdad. ‘All my life, I have worked on Palestine and it has only got worse,’ she said. ‘I wanted to write about something else, for my own mental health.’

The specifics of the cruelty in recent weeks have shocked Atef: the social media posts by Israeli soldiers joking ‘It’s a boy!’ against photographs of blue smoke billowing out of a newly bombed Gaza building; the Israeli army calling a man in Gaza and telling him either to stay where he is and be killed with the hundred or so people around him or to walk up to the bank of a sand and be killed alone. ‘What did he do?’ I asked. ‘He walked away from the group and they killed him alone,’ Atef shrugged: that much should have been obvious. ‘It’s been a terrible few days,’ he wrote in a later email. ‘Too many innocent relatives killed in the last few days. Just awful.’

My friend Marwa moved back to her home in the north of Gaza and travelled south every day to work for a humanitarian organisation. A two-and-a-half hour journey. When I asked her yet again how things were, in late April, she replied:

What I can say Selma … 99 per cent of the people are sleeping hungry … one third of your salary goes to anyone who can give you cash … nothing entering for the basic needs for more two months, no cooking gas … if they could put the oxygen in bottles and not allow us … they will do so.

During the week of 15 May the playwright Ahmed Najjar lost his six-year-old niece, Juri, when the family home was hit by an Israeli airstrike. The playwright Ahmed Massoud lost his brother, Khaled, months ago when he was shot by an Israeli quadcopter as he tried to help others. Khaled lost his leg and bled to death before anyone could reach him. His wife, Ibtisam, and 17-year-old son, Mahmoud, were killed within hours of the strike that killed Juri. Both Najjar and Massoud can only watch and support from afar.

The journalist Ahmed Alnaouq, also based in London, lost his entire family in an airstrike on Deir al-Balah where they sought safety on 22 October 2023. He is the co-founder of We Are Not Numbers, which advocates for Palestinian voices to be heard unfiltered. On 6 May, at the London launch of the bestselling book he edited with Pam Bailey, We Are Not Numbers: The Voices of Gaza’s Youth, he spoke of the catharsis of writing, and the guilt of surviving. ‘Why am I here wearing a suit, sitting here on a London stage?’

On 25 May Alnaouq interviewed Shawan Jabarin, the general director of al-Haq, a Palestinian human rights organisation. ‘By defending the Palestinians, you defend human values,’ Jabarin said. Al-Haq – with the support of Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Oxfam and the Global Legal Action Network – took the UK government to court for continuing to supply arms to Israel, specifically parts for F-35 fighter jets. In September 2024 the UK government suspended thirty arms export licences to Israel, with an exemption for F-35 components that went through third countries. ‘The F-35s probably killed my family,’ Alnaouq said.

The Campaign Against the Arms Trade has found that between October and December 2024 the Labour government approved £127.6 million in military licences to Israel, most of them for targeting equipment, software, military radars and components.

The case, still awaiting judgment, was heard at the High Court between 13 and 16 May. On 15 May, the Spanish premier declared Israel a ‘genocidal state’ that Spain would not do business with. The Irish deputy prime minister, Simon Harris, said on 16 May that he hoped Ireland would no longer be in such a ‘lonely place’ when it came to their position on the EU-Israel trade agreement and condemning the Israeli government’s actions more generally. By the weekend, the BBC’s international editor, Jeremy Bowen, was asking which side of history the UK wishes to find itself on.

On Monday, 19 May, a joint statement by the governments of France, the UK and Canada spoke of taking ‘concrete action’ against the ‘egregious actions’ of the Netanyahu government. On Tuesday, 20 May, the British foreign secretary, David Lammy, told the House of Commons that ‘we have suspended negotiations with this Israeli government on a new free trade agreement’. Lammy described actions by the Israeli government and its settlers as both ‘abominable’ and ‘extremism’. I was shocked – moved, even. ‘We have come to expect so little,’ the Paris-based writer Karim Kattan said in a BBC World Service interview that I also took part in. The shift in vocabulary felt dramatic, even if the shift in policy has been slight so far.

Scottish newspapers the next day reported on the continuation of RAF surveillance flights over Gaza. On 15 May, a private party at the British Museum had celebrated Israel’s creation in 1948 and UK ministers boasted of the strong military ties between the two countries. Humanitarian aid and international reporters continue to be denied entry into the Gaza Strip and the young, encaged population continues to be bombed, burnt and starved. A week after Lammy’s pronouncements, on 27 May, the UK trade envoy to Israel was writing on X that he was in Israel to ‘promote trade with the UK’.

MPs at Westminster said on 21 May that 14,000 babies would starve in 48 hours if aid was not let through. The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights reported that attempts by Palestinian security forces to protect trucks from looters when they entered Gaza resulted in attacks by Israeli quadcopters. Israeli civilians continue to protest at crossing points, disrupting the entry of aid into Gaza and attacking it where possible. According to social media reports coming out of Beit Hanoun, in the north, minutes after aid trucks arrived with meat and vegetables that the residents had not seen for months, Israel dropped evacuation orders, soon followed by bombs, before people had a chance to eat anything.

On 14 May, the eve of Nakba Day, I was at a cinema in Soho watching Forensic Architecture’s reconstruction of Salman Abu Sitta’s experience of the catastrophe in the village of al-Ma’in. He was eleven years old in 1948. The computer-generated video reproduces the school his grandfather built, the homes, the gully, the busy crossroads, the Bedouin tents, the crops. Abu Sitta had been told that people were coming from different places to take his home. He could not understand why. ‘Yes, that’s where I hid,’ Abu Sitta says in the film, pointing to the gully. From there he could see the dark smoke rising from the wool tents as they burned. Seventy-seven years later, Palestinians are still being displaced and burned alive in tents. The Nakba was not a one-off expulsion, but continues. The demonstration in London on 17 May was one of the largest I have known, estimated at half a million by the organisers (twenty thousand by the Metropolitan Police).

On 15 May, Professor Ghassan Abu Sitta (Salman’s nephew) gave the annual Centre for Palestine Studies lecture at SOAS, on the biosphere of genocide. What Israel has created in Gaza is an environment so toxic to human life that the unnaturally high level of deaths (at least 54,000 since October 2023) would continue even if the bombing were to stop immediately and all forms of aid were to be allowed in. Before October 2023, two women per year died in childbirth in Gaza; now the number is at least five per month. There is no water, no sanitation. Rats are everywhere. The environment is filled with carcinogens released by explosives.

Of the 36 hospitals in Gaza, 33 have been destroyed. If you’re malnourished, it takes longer for your wounds to heal. Antibiotics are hard to come by, and the bacteria in many infected wounds are resistant to them. Health workers are more than twice as likely to be killed as other people, and more likely to be tortured if they’re taken into detention. Better to kill yourself before they take you in, one former detainee warned on social media. They treat doctors the worst. The question, Abu Sitta said, is why, if Gazans are dying at such a rate, Israel continues with its bombardment. Referring to Frantz Fanon, he suggested that the purpose of the violence went beyond its direct physical effects, as a performative display of omnipotence.

‘I want to talk to you about the political class,’ the British plastic surgeon Tom Potakar said in a video recorded in the European hospital in Khan Younis before it was bombed. ‘They have no idea how dangerous their words are … Perhaps if they spent not twenty months, not even one month, but just one day here, they would have the courage and the humanity to speak the truth.’

One killing can cut you to shreds, even among so many thousands of others. Eleven-year-old Yaqeen Hammad was killed by Israel on 23 May. She had taken to social media during the genocide to make videos showing, for instance, how to devise contraptions to cook on, despite Israel cutting off the gas. ‘In Gaza, nothing’s impossible,’ she would say, smiling brightly at the camera.