Serious Music

Liam Shaw

Anyone who plays an instrument – or has shared a house with a musician – will be familiar with the maddening nature of repetitive practice. Many piano players have bought Charles-Louis Hanon’s The Virtuoso Pianist in Sixty Exercises,but few complete it. One reason is that skills tend to plateau, after which it takes considerable fortitude to persist.

The pain of practice can be physical as well as mental. For concert pianists, the hours spent chasing peak performance can lead to severe muscular spasms. Pianists who injure themselves through playing are caught in a desperate bind: attempting to return to practice only exacerbates their condition; without it, their skills atrophy. Robert Schumann’s teenage ambitions of virtuosity were undone by the onset of debilitating pain in his right hand. ‘It came to such a point that whenever I had to move my fourth finger, my whole body would twist convulsively,’ he wrote to a friend. Trying to make his fingers stronger he experimented with mechanical devices that probably banjaxed them irreparably.

A new paper in Science Robotics reports a device that Schumann would have jumped at the chance to try: a robotic exoskeleton for the hand. The apparatus, developed by roboticists at Sony Computer Science Laboratories in Tokyo, resembles a fingerless glove that can open and close the wearer’s fingers individually up to four times a second.

The lead researcher, Shinichi Furuya, was once an aspiring piano virtuoso. As he explained in a talk in 2017, in his teens he spent up to ten hours a day practising. The punishing schedule led to recurrent hand pain that no doctor could cure. His career since has focused on studying the mechanics of piano-playing – and, more recently, the potential application of robotics. He founded the NeuroPiano Institute in Kyoto, which aims to allow musicians to ‘surmount the limits of creativity’.

The greatest musicians are aware of their own limits. As a teenager, the jazz pianist Oscar Peterson heard a record by Art Tatum for the first time: he thought it was two people playing. When he was told it was a single pianist, he was so intimidated he gave up the piano for two months. Even to great players, Tatum’s abilities seemed inimitable. There’s an apocryphal tale of Rachmaninoff hearing Tatum in concert: ‘If this man ever decides to play serious music we’re all in trouble.’

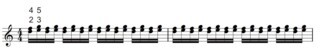

Furuya and his colleagues tested whether their exoskeleton robot could lend a hand. The study participants were expert pianists: all had started playing the piano before eight years old, practised for more than ten thousand hours by the age of twenty, and studied piano performance at a conservatory. In the first study, thirty of them were given two weeks to practise a chord trill with the right hand – a quick alternation between pairs of fingers similar to the start of Chopin’s Étude Op.25 No. 6 (though in a different key):

They practised in bursts of ten seconds at a fixed tempo, repeating thirty bursts every morning and afternoon. Regular tests, in which they tried to play the trill as quickly and accurately as they could, confirmed that after early improvement – shaving about a hundredth of a second off the initial gap between the notes – their ability plateaued. Then, they came into the laboratory and put their hand into the exoskeleton for some ‘passive training’ away from the piano.

For half of the pianists, the exoskeleton furled and unfurled all their fingers together; for the other half, it made them perform the same finger movement they had been practising but at twice the speed. After removing the exoskeleton and performing the chord trill on a piano half an hour later, those in the latter group could do it faster – with about five-hundredths of a second less between notes. The difference persisted a day afterwards.

To test whether it was simply the exoskeleton’s movement or the speed of it that made a difference, the researchers carried out another study on a different set of pianists. On one group the exoskeleton performed the movement slowly, on the other quickly. Unsurprisingly, it was only the quick group who sped up. But, surprisingly, each pianist’s left hand – the untrained hand – also sped up. That transfer effect suggests that something about the ‘somatosensory experience’ of performing the movement quickly with one hand made the skill improve for both. The paper marshals some tentative evidence that neuroplasticity may be responsible: knowing what it feels like to play like Art Tatum helps you to play faster.

It remains to be seen both how long the effect lasts and whether the finding can be generalised. It seems possible, for example, that the improvement only occurred because of the constraints of the practising regime that the researchers imposed. And there is far more to being a pianist than sheer speed. The pursuit of technical difficulty has its absurd conclusion in Conlon Nancarrow’s deranged and demonic studies for player piano – deliberately written to be impossible for any human to play. But with an exoskeleton, who knows?

Comments