Here and Now

Sam Kinchin-Smith

Time-specific art extends the principles of site-specificity into the fourth dimension, by integrating circadian rhythms or extreme duration, say, into its performance language, or by staging a work to coincide precisely with when it’s set. There seems to be a lot of it about, at the moment, perhaps because it offers a live corrective to the always on, ever present homogeneity of digital culture.

‘The ephemerality and transitory nature is its power,’ as Séan Doran puts it. ‘You either got to it or you didn’t.’ Doran is the creative director of Arts Over Borders, who have just announced two new programming strands. FrielDays: A Homecoming will put on 92 productions of Brian Friel’s 29 plays over the five years leading up to his centenary in 2029, with each performance presented in a setting relevant to its themes, in the season and at the time of day in which the action happens. ‘It’s all there, in the scripts – “afternoon”, “late afternoon”, “late August” – it’s not superimposing anything,’ Doran told me.

The Beckett Biennale, meanwhile, will present in 2036 and 2038 ‘one of the most forward-thinking pieces of artistic programming ever’ with new productions of Krapp’s Last Tape. Samuel West and Richard Dormer will perform in conversation with their younger selves, having been encouraged by Doran to make recordings of the taped speeches in 2006 and 2008 respectively, in the world’s first literal fulfilment of Beckett’s directions in his script. In the meantime, Oh My Godot! will stage an annual reinterpretation of Waiting for Godot in and around Enniskillen, where Beckett went to school. The timings will somehow coincide with the chronological sequence of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, in ways I still don’t fully understand. (Beckett was born on Good Friday, 13 April 1906.)

I asked Doran how he came to start working in this way. ‘It was an epiphany moment,’ he said. He went to Australia as director of the Perth International Arts Festival from 2000 to 2003:

As a European, virtually touching the ground off the plane, you recognise you’ve no memory, suddenly, and that’s an exciting prospect, rather than a diminishing one. It was meeting the Aboriginal culture, and I have absolutely no shyness in expressing how altering that was, in a flash. I felt I was staring back into deep time, in the presence and the engagement of that culture. And also feeling how robbed of it we are in white Western society.

This led to such experiments as a performance by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company on Cottesloe Beach, where the sudden Western Australian sunset became the blackout at the end of the piece. But it was when he returned to Ireland that Doran’s approach to festival programming found its fullest expression. I asked him if he thought Ireland was especially receptive to this sort of thing: the immersive production of The Dead staged at Dublin’s Museum of Literature over Christmas (with two performances on Epiphany night), for instance – not to mention Bloomsday. Is a boozy day following the route of Ulysses simply an easier sell than actually reading the novel, or is there something else going on? Doran was sceptical:

I think Ireland has lost and distanced itself from what I spoke about, in terms of Aboriginal culture. We really have lost our myths and language. But as a northerner, because of the Troubles, I would argue to an extent we are hardwired with a historical sense of time – very precisely, 14 July, 12 August, 1689 etc. It goes back four hundred years. The south shed this a hundred years ago to its benefit, but then what do you lose? And I’m one of those who believes the marches should stay because they are one culture’s legitimate renewal and ritual. They’re so important, those turning points of time.

The turn of the millennium was part of the inspiration for Jem Finer’s Longplayer, a thousand-year musical composition for Tibetan singing bowls that started playing – continuously online, through algorithmically arranged recorded samples, and very occasionally in live performances – on 31 December 1999. (I am the chair of the Longplayer Trust, the charity entrusted with the custodianship of the project.)

Long-term and durational artworks don’t always fit neatly in the category of the time-specific, since many of them are defined by other kinds of specificity. Erik Satie’s Vexations is a one-page score, a lilting motif for piano, with the instruction to the performer to repeat it 840 times. Igor Levit will play it at the Southbank Centre on 24 and 25 April, introduced by Marina Abramović. The performance is expected to last between sixteen and twenty hours.

Vexations was rediscovered by John Cage in the 1960s, and Cage’s shadow looms large in this area of experimental music. But while 4’33”is probably the greatest work of time-specific art ever conceived (Doran is in the early stages of planning a big international performance), ORGAN2/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible) is radically unspecific, inviting ever-longer interpretations. A performance began in St Buchardi church in Halberstadt in 2001 and is due to end in 2640. The most recent note was played on 5 February 2024. The next will begin playing on 5 August 2026.

Longplayer complicates the idea of liveness as a corrective to digital mass reproduction, by instead offering a window into the workings of its algorithmic engine through live performance. There’ll be a thousand-minute rendition (the first in the UK since 2009) this Saturday, 5 April, at the Roundhouse in London. I asked Finer to explain how it will work:

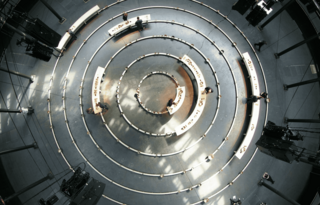

What you’ll see at the Roundhouse is a literal physical transformation of the Longplayer score. On the score you have six concentric circles; in the Roundhouse you’ll have six concentric circular tables … the widest is about twenty metres in diameter. And on each ring of the score there are 39 gold circles that symbolise singing bowls; if you look on the tables you’ll see in exactly the same places the actual singing bowls. But for reasons of cost and economy, we don’t actually have 360 degrees of each table, and all the bowls out on each table, because in a thousand minutes we’ll only have to play certain sections.

The yellow highlights on the score show the two minutes of each circle that’s currently playing. Every two minutes, each section moves on slightly clockwise, at different rates (with the third circle, the increments are so small that a single circuit takes the entire thousand years). The tables at the Roundhouse are just long enough for the musicians to play those thousand minutes. The rest of the rings are represented only by a ‘skeletal track’.

It’s a physical expression of the piece that immediately makes it more comprehensible than any written explanation can, and it seems intensely time-specific to me, but for Finer, it isn’t only that, ‘because it’s an excerpt from something that’s much bigger: at the temporal boundaries at the beginning and end of the piece, there’s a fuzziness, and you can see back into the past and way into the future. Longplayer is for the listener who doesn’t have access to time travel.’