At the Tom Verlaine Book Sale

Alex Abramovich

A meme bounced around Brooklyn last summer: ‘What if we kissed at the Tom Verlaine book sale?’ Verlaine, who formed and fronted the band Television, died on 28 January 2023. Over the years he had acquired fifty thousand books – twenty tons or more – on any number of subjects: art, acoustics, astrological signs, UFOs. The sale of those books – a two-day affair in August, run out of adjacent garages in Brooklyn – was a serious draw. Arto Lindsay, the avant-pop musician, walked by. Tony Oursler made a short video and posted it on Instagram. Old friends, some of whom looked as if they hadn’t seen daylight in decades, found each other in the long line.

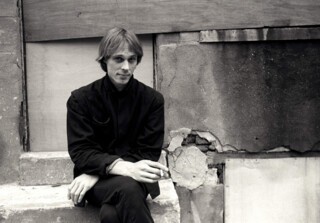

Verlaine had split his enormous collection between storage units: one a short walk from his Chelsea one-bedroom, four more across the river in Red Hook, near the foot of the Gowanus Canal. Verlaine didn’t use Uber. To get to the Brooklyn facility he’d take a rickety grocery cart on the F train, ride it out to Smith and Ninth Street, the highest Subway station in the city, and walk the rest of the way. In a crowd, Verlaine stood out. He was tall, thin, fine-featured. (‘Tom Verlaine has the most beautiful neck in rock and roll,’ Patti Smith wrote in 1974. ‘Real swan like.’) He had never quit smoking and wore a car coat, like a character out of film noir. But there he had been, bumping his cart down several sets of stairs and escalators and wheeling it, under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, across seven lanes of traffic, to Red Hook. The books had to go somewhere.

Verlaine had been a regular at the Strand, where he’d once worked in the shipping department – you’d see him on the sidewalk in front, where the dollar carts were. On tour, he used the space between soundcheck and showtime to visit local booksellers. In Brooklyn, he had packed his storage units so tightly that Patrick Derivaz, the friend charged with handling his estate, had to rent another unit just to have space to move boxes around. Jimmy Rip, a guitarist in Television’s most recent incarnation, had flown in from Argentina in January; seven months later he was still in New York, helping out. Dave Morse and Matty D’Angelo, of the Bushwick bookstore Better Read than Dead, had come aboard too.

‘Usually,’ Morse told me, ‘people call and say: “We have fifty thousand books.” You get there and it’s more like five hundred. In this case, we counted the boxes. It was maybe a little less than fifty thousand, because Verlaine was really good at packing. He used a lot of filler. He’d improvise squirrel nests: folded pieces of corrugated cardboard and bubble wrap. He was scrappy about it but very meticulous and, for the most part, the books were in excellent shape. We did the math, scratched our heads, realised we couldn’t do it alone. We thought about dealers we knew who had space.’

D’Angelo mentioned Capitol Hill Books in Washington DC. It had a sister company called Bookstore Movers, and access to a truck that Derivaz was now minding in front of the Brooklyn garages. The books inside were sorted by subject: ‘Literature’, ‘Poetry’, ‘Religion’. D’Angelo had created a new category, ‘MOPS’, for mythology and mysticism, the occult, paranormal activities and spirituality: books about whirling dervishes, Aleister Crowley and Anton LaVey, shelved next to chapbooks, cookbooks – though the only thing Verlaine ever made on a stove was coffee – and books about China. As a reader, Verlaine went on jags: psychology, radical theory. But there were subjects he kept returning to and interests that seemed to date all the way back. In his 2013 autobiography, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, Verlaine’s one-time best friend and bandmate Richard Hell describes him as a very young man:

Most of the world seemed incomprehensibly weird to him, and he was susceptible to all kinds of irrational explanations for that, from things like flying saucers, to extreme conspiracy theories, to obscure religious mysticism. He knew that these beliefs, or suspicions, would seem crazy to a lot of people and that was part of why he was so private.

A few days after the book sale I walked down to the Red Hook facility to meet Rip and Derivaz. They showed me a unit full of amps, speaker cabinets and vacuum tubes, which Verlaine had also collected. ‘If a song was in the key of E flat,’ Derivaz said, ‘Tom would swap in a tube. Here, you see how he had marked them.’

At the sale there had been a catalogue – The Tube Amp Book: Fourth Edition – sandwiched between a biography of György Ligeti and a history of Blue Note Records. I now regretted not picking it up. Verlaine had new vacuum tubes he’d shipped from Slovakia, where they are still being made. He had vintage tubes that he’d got off eBay, or bought before eBay existed. He had hundreds and hundreds of tubes.

Verlaine did not go in for expensive equipment. (Dean Wareham, of Luna and Galaxie 500, remembers Verlaine turning up in the studio with a barely playable twelve-string electric, which he proceeded to play beautifully, and touring in Europe with no equipment at all, renting a new Stratocaster in each city.) But he was particular about his tone. Like Jeff Beck, Verlaine plugged straight into his amps, working the volume and tone knobs of his guitar to get effects other players could create only with a pedal. He was perhaps sensitive to a fault. Rip recalled one of their soundchecks: ‘Tom stopped. He said: “I hear a buzzing.” We didn’t hear anything but Tom insisted. We looked for the buzz and we finally found it, way, way in the back of the room. You had to be underneath it to hear it, and Tom noticed it from the stage.’

‘Tom was highly protected,’ Hell wrote in his autobiography, ‘well defended. There are good things and bad things about that. It gave him a certain kind of integrity – he wasn’t going to be blown around by fashion, he was discreet and reliable, but it made him really difficult to work with.’ But for six years or so, Verlaine and Hell – who had run away from high school in Delaware together, and found each other again in New York – were inseparable. They lived in the same apartment, slept on the same double mattress, wrote poems together as ‘Theresa Stern’ and published them at Dot, the poetry imprint Hell ran. (His first publication was a book of poems by Andrew Wylie.)

In 1972, they formed a band. Verlaine picked out a bass guitar from the pawn shops on Third Avenue and taught Hell the basics. They cut their hair, changed their names (from Meyers and Miller to Hell and Verlaine), called themselves the Neon Boys, and brought Billy Ficca in. For a few months, they rehearsed in Verlaine’s apartment. They didn’t have money for amps or a kit; Ficca, a brilliant, jazz-oriented drummer, drummed on phone books instead. Hell wrote ‘Love Comes in Spurts’, ‘Blank Generation’, ‘Eat the Light’ and a few other songs. Verlaine wrote ‘Bluebirds’, ‘$16.50’ and ‘Tramp’. They put an ad in the Village Voice – ‘Narcissistic rhythm guitarist wanted, minimal talent OK’ – and auditioned several people (including Doug Colvin, who became Dee Dee Ramone, and Chris Stein, who went on to form Blondie), none of whom seemed to fit. By now, it was 1973. Hell and Verlaine were working at Cinemabilia, a small store on 13th Street. The manager, Terry Ork, recommended Richard Lloyd, who had been crashing at his Chinatown loft, and with Lloyd as their second guitarist they changed their name to Television.

Hilly Kristal, the owner of CBGB, had been planning to feature country, bluegrass and blues bands at the club. Ork, who was now managing Television, convinced him to feature his band instead. Gradually, a scene formed. Television recorded a demo with Richard Williams and Brian Eno, who would have produced their first album if Verlaine hadn’t hated the sound. Verlaine was convinced that Eno took the tapes back to England: he thought he heard his ideas in the grooves of Roxy Music’s next album. Whether or not that was true, at around the same time Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood copied aspects of Hell’s look – spiky hair, torn T-shirts, safety pins – and attitude, and pasted them onto the Sex Pistols. ‘When we played,’ Hell recalled, ‘it was like a rolling, tumbling clatter of renegade scrap that was also pretty and heartrending, as if you were seeing it from a distance. It moved you and shook you and woke you up.’

By the time Television recorded their first album that version of the group was gone. Gradually, then not so gradually, Verlaine had pushed Hell, and Hell’s songs, to the side. He put years of rehearsal, refinement and thought into Marquee Moon, which came out in 1977, two years after Hell’s departure, with Fred Smith playing bass in Hell’s stead. The songs were structured more carefully now, written out like short stories. Verlaine loved John Coltrane and Albert Ayler; the bulk of his record collection was made up of jazz albums on labels like ESP and Impulse. But even in concert, when Television was noisy and free, the interlocking solos played by Verlaine and Lloyd were highly arranged – ‘filigreed’, as Williams put it.

The songs were ‘literary’ in a literal sense, too – something that’s seldom a virtue in rock and roll, but it worked for Verlaine, who seemed to be writing detective stories, filled with clues, cops, double-crosses and other hard-boiled bric-a-brac, and shattering them. Five of the eight songs on Marquee Moon tell stories that take place at night. Four switch between the past and present tense. Verlaine’s images are startling: ‘I want a nice little boat/made out of ocean’; ‘the world was so thin/between my bones and skin’; ‘I recall/lightning struck itself.’

But if the Television that prefigured punk – the group Hell was part of – was anarchic, and the Television of 1977 was controlled, almost to the point of being programmed, it’s a mistake to think of them as two different bands, or to see Hell and Verlaine as opposite persons. Verlaine’s singing was high-strung and urgent. His album was still a performance, recorded quickly and more or less live. It was strange, desperate, wonderful: ‘Pull down the future with the one you love,’ Verlaine sang, ten times in a row, at the end of the first track. He and Hell had the ecstatic in common.

Of course they hated each other. ‘I can’t stand the guy,’ Verlaine would say, and Hell never pulled any punches. In the epilogue to I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, Hell described running into Verlaine for the first time in a very long time:

The other night I was walking home from a restaurant when I saw Tom Verlaine going through the dollar bins outside a used book store … I walked up to him and asked: ‘Finding out anything about flying saucers?’

Hell describes Verlaine’s teeth (‘even worse than mine’), his face (‘porous and expanded’) and hair (‘coarse grey’):

I turned away and walked on shocked. We were like two monsters confiding, but that wasn’t what shocked me. It was that my feeling was love. I felt grateful to him and believed in him, and inside myself I affirmed the way he is impossible and the way it’s impossible to like him. It had never been any different. I felt as close to him as I ever did. What else do I have to believe in but people like him? I’m like him for God’s sake. I am him.

You can still buy Verlaine’s books from Better Read than Dead and Capitol Hill’s websites. His record collection will go on sale, one of these days, at the Academy Record annexes in Greenpoint and the East Village. They’re a reminder of different days in a different city, where the bookstores and record stores stayed open late, and you could poke around in them even after a night out at CBGB, and the stuff that you’d get there was cheap, and the space that you needed to store it was cheap, and, even if you worked in a bookstore, you could afford an offset press and start your own poetry imprint, or find a loft space in SoHo and start your own band.

Comments

-

6 March 2024

at

6:42pm

gary morgan

says:

A touching piece and unusual to see the sensitive side of Richard Hell for a change.

-

6 March 2024

at

6:45pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Gary, if you follow the links in the last paragraph, they'll give you an idea.

-

6 March 2024

at

8:12pm

Chris Paparella

says:

A beautifully written tribute to a remarkable man and an unusual friendship. Is it meta to say I bought Television’s Adventure from a cut out bin?

-

7 March 2024

at

11:40am

Tomi Koljonen

says:

Lovely piece, made me put Marquee Moon on.

-

7 March 2024

at

7:59pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Didn't make it into the piece, but TV and Patti Smith used to joke about opening a second-hand bookshop together: "Olde Tom's Books."

-

8 March 2024

at

4:58pm

gary thomas

says:

As you observed, Hell's look seemed to have filtered through McClaren to John Lydon, but the latter has never acknowledged this in any of his autobiographies. Marquee Moon, Verlaine's masterpiece, had a massive impact on the 'post-punk' music UK scene after the Pistols split. I do believe 'Little Johnny Jewel' is a work of genius.

-

9 March 2024

at

4:17am

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

gary thomas

Gary, I don't know about Lydon, but FWIW, Malcom M did acknowledge it. He'd been in NYC, managing the NY Dolls. It's not conjecture on my part...

-

8 March 2024

at

8:56pm

Andrew Pearmain

says:

Lovely, touching piece about special times, places and people. I loved the solo albums, where TV seemed to spread out a bit. Saw Television a couple of times in the later years, clearest memory is of Tom constantly tuning and retuning. Very awkward stage presence, very un American, good for him!

Read moreTom is no less an enigma though; I should have guessed he'd have plugged his guitar straight into his amp like that other outsider, Jeff Beck.

Seems he was a collector of curios. As for the books, it'd be interesting to know what poetry he read. I'd like to think Robert Merrill, Wallace and Rimbaud.

RIP Tom.

Cheers,

Aa