In a Different Medium

Viktor Wynd

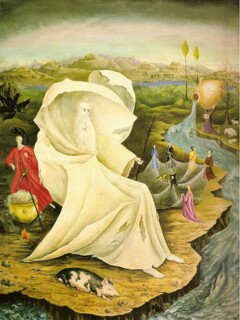

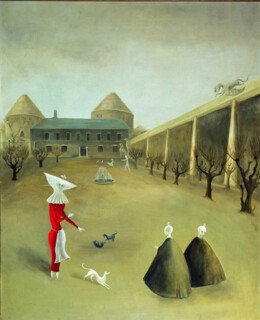

Leonora Carrington was not, until recently, a household name, though anyone with a more than passing interest in 20th-century art, especially Surrealism, knew her work. It was displayed in many of the world’s modern art museums, from the Tate to MoMA. The Serpentine gave her a solo show in the 1990s and in 2015 there was a large retrospective, curated by Francesco Manacorda and Chloe Aridjis, at Tate Liverpool. Carrington’s extraordinary self-portrait with a hyena and a rocking horse escaping through an open window – The Inn of the Dawn Horse – was plastered all over London as publicity for the Tate’s rather chaotic Surrealism show in 2022. More recently Sotheby’s sold a painting by her for $28.5 million, crowning her as the ‘most expensive British female artist of all time’, a dubious honour that would have appalled her.

Carrington was born in Lancashire in 1917, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist. She found her upbringing stultifying and escaped as soon as she could, eloping to Paris with Max Ernst in 1937. Her parents were horrified but supported the pair financially, even buying them a house in the South of France. She fled the Nazi invasion, spent time in a psychiatric hospital in Spain and married a Mexican diplomat – in part to allow her to move first to New York and then to Mexico City. She died in 2011 at the age of 94. But many people have interesting lives: Carrington also spent most of hers making art, examining inner worlds of dreams, magic, mythology and much else.

Now is a difficult time to try to mount an exhibition of her work: there are major museum shows springing up around the world, so it’s admirable that the small Newlands House Gallery in Petworth has tried. Unfortunately – presumably because they have not been able to obtain more than a handful of interesting pieces – the show has been obliged to focus on Carrington’s biography, with large photographs and well-written panel pieces.

There are two or three minor paintings, a handful of sketches, the wonderful lithographs from the 1970s illustrating S. An-sky’s Dybukk, some masks that Carrington made for a friend’s production of The Tempest and – well, it’s hard to know what to call the bulk of show. I certainly wouldn’t call it art. An abomination, rather: poor quality, lurid reproductions of some of her famous paintings, labelled as lithographs and priced at over £7000 each, in editions of 100, signed, if we are to believe the labels, by Carrington moments before she died (a signature remarkably different from the one she made in my copy of The House of Fear a few years earlier); and bronze sculptures dated to the last couple of years of her life – all for sale for hundreds of thousands of pounds.

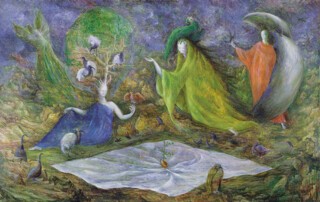

It is difficult to imagine that these bronzes were made by the same hand as the paintings, drawings, tapestries, writings and earlier sculptures. When I asked the gallery’s director if she was sure they were by Leonora Carrington, she said their authenticity had been confirmed by Carrington’s younger son, Pablo Weisz Carrington. Carrington was photographed (looking rather glum) with some of them. But I have spoken to most of the experts on her work – museum curators, art historians, dealers and collectors – and while few of them are willing to be quoted, they are unanimous in their dislike of these late sculptures and in their feeling that she can have been only minimally involved at best. There are supposedly thousands of them, but only a handful of the earlier, very well documented bronzes are ever included in museum exhibitions of Carrington’s work or in scholarly books about her. Blue chip art dealers, auction houses and collectors who specialise in her work will not touch the others.

People who were close to Carrington have described to me, off the record, her intense disgust at many of these works. In 2009 she would make sure not to be driven down Paseo de la Reforma, one of Mexico City’s main avenues, because the pavements had been filled with enormous sculptures she did not want to see.

One senior curator diplomatically told me that when putting together an exhibition one only wanted to show the best work by an artist and so would never include the bronzes, but they asked not to be quoted for fear this could be misinterpreted as authenticating the works, which they declined to do.

The scholarly consensus seems to be that Carrington was not actively involved in many – or most – of these late career sculptures. Marina Warner told me they were ‘versions of works she made – interpreted in a different medium’. It seems likely that some of them are reinterpretations of drawings or paintings, possibly based on sketches. Later in life, with the help of her dentist, Isaac Masri, who acted as intermediary between her and the foundry, she made little models in plasticine – there was one on the bench in her studio when I visited her in 2008. Some of them seem to have successfully made the jump into bronze, but many have been transformed beyond recognition, blown up into vast soulless structures with the precise proportions lost and one struggles to see the hand of the artist (or any artist). ‘I worked very closely with Leonora for thirty years,’ Dr Masri told me. ‘Some of the pieces in this show are made by Leonora with me as promoter however the vast majority are copies in other sizes or fragments of them.’

In his memoir The Invisible Painting, Carrington’s son Gabriel Weisz Carrington writes:

I cannot avoid mentioning what happened to the sculptures attributed to Leonora after her death. I hate to think of those untalented thugs who abused her absence in order to promote a series of bronze monstrosities in her name. It is easy to see the creative weakness of these items sold and displayed in Mexico in comparison to the authentic sculptures produced by Leonora. You can feel the heavy-handedness of swindlers who tried but never succeeded in recreating her skill. The few sculptures she did create display elegance and artistic balance, qualities that are entirely lacking in those vulgar heaps of bronze, devoid of imagination as they are. I hate that these adulterations are being displayed all over the place, pretending to be authentic art, art that is being replaced by objects made by buffoons and self-promoters.

Many people I spoke to, including Dawn Ades, compared the bronzes to the ‘almost Salvador Dalí’ trade in bronze melting clocks, long-legged elephants and so on that were authorised by Dalí in the last years of his life (inasmuch as he signed many pieces of paper that he may or may not have read). They pop up from time to time – there was even a ‘Dalí Museum’ dedicated to them on London’s South Bank at one time. Like the later Carrington bronzes, however, they are never included in museum shows, do not appear at auctions or art fairs and are not commonly considered to be of interest.

Photographs of Carrington’s home in Mexico City, now a museum, show it stuffed to the gills with these monstrosities, which visitors to the house in her lifetime do not recall being quite so prominently displayed, if they were present at all. When I look at the bronzes, I am reminded more of the replicas sold in museum shops, models of the sphinx or the Eiffel Tower. As they often refer to important pieces by Carrington, I can only hope that they draw attention to her other work rather than distract from it. That she is now better known than ever before can only be celebrated, but it would be a shame if this misguided show, however well-intentioned, helped usher in her celebritisation (the Wall Street Journal has called her ‘a new Frida Kahlo’; heaven forbid). I would advise anyone curious about Carrington not to go to Petworth, but to read instead the reissued collection of her stories by Silver Press and Susan Aberth’s book Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art.

Comments

Shane Anderson, Bangkok