In Pope’s Grotto

Gillian Darley

London Road, Twickenham is a busy street through a bland, largely residential area which presents a resolutely respectable face to the world. The Thames is nearby but out of view. A few hundred metres away is Eel Pie Island, once a hive of alternative living, and Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House is a little further upriver. But directly underfoot, or under the tarmac and tyres, also completely invisible, is a place synonymous with some of the sharpest minds of the early 18th century, Alexander Pope’s grotto.

The way into the grotto runs under a school and beneath the road, through a stony tunnel that ends up meeting a blank rear wall, part of a different school on the other side of the road. Out of these drab, confusing surroundings you step into a long rock-walled passage, now ‘candlelit’ by LED, from which you can explore two small chambers with a larger oval room between them. All are encrusted with minerals.

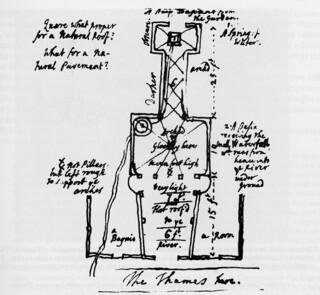

Over more than twenty years, Pope’s grotto was made and remade, as he explored a succession of ideas and connections. The friends and visitors he welcomed there recorded what they found with astonishment, in words and images. This was not, as Yue Zhuang and other scholars who have studied the enterprise make clear, an aesthetic frolic but a profound investigation of ‘all the varieties of nature’s works under ground’.

Pope died in 1744. His house was demolished in the early 1800s and his gardens obliterated (as he put it at the end of the revised Dunciad of 1742, ‘universal darkness buries all’).

Yet as Barbara Jones made clear in Follies and Grottoes (1974), the grotto as a feature of the English pleasure or landscape garden was essentially pioneered by Pope. Few who followed him would match his ambitions, however, which were as encyclopedic as (and considerably more coherent than) those of Athanasius Kircher. (When John Evelyn visited the Jesuit polymath in Rome in the 1640s, he was left open-mouthed by the things he saw in Kircher’s room-sized cabinet of curiosities.)

Over time, Pope’s endeavour altered focus. His collection of scintillating materials – gems, precious ores and shells, with mirror glass inserts, illuminated by a lamp hanging from the centre of the chamber – morphed into something less eye-catching but intensely investigative, as fossils, sections of basalt and a simulacrum of a mine were fixed to the walls and ceilings of the grotto in the cellars of his Thames-side villa. Advice came from the Cornish cleric and geologist William Borlase; minerals (and encouragement) from Pope’s quarry-owning friend, Ralph Allen of Bath. He even found a spring, which may have made its way into his description of Calypso’s cave in his translation of the Odyssey:

Four limpid fountains from the clefts distill,

And ev’ry fountain pours a sev’ral rill.

Over time, the subterranean profusion was vulnerable to light fingers and the shifting strata of the riverside earth, let alone the disagreements that opened between admiring scholars. The exact form and dimensions of his creation, seen in early drawings by Wiliam Kent and others, but probably subject to later extensions and embellishments, are questionable. The latest painstaking conservation work enhances what remains and gives clues to what has been lost.

The unveiling and renewal of the grotto has been a long process and is not yet over. The Pope’s Grotto Preservation Trust was set up in 2014 as a heritage charity, giving it access to capital with which to appoint architects and conservators, notably Donald Insall Associates and Taylor Pearce Restoration Services. In the same year the school changed hands and arrangements for access out of school hours became feasible.

Much of the recent work has seen the removal of inappropriate materials, in particular the cementitious screed laid over the original brick floor and cement and pebble dash elsewhere which disguised key features of the original structure. The source of the water – which must have been so important to the sensory programme of the grotto, playing in the glittering cave, enhancing the reflections from mirrors and crystalline minerals – is still elusive. Pope’s grotto still harbours secrets, just as you would hope.

Comments

Approach: But aweful! Lo’ the Ægerian grott,

drawing on Juvenal’s Third Satire, on forsaking of the corruption of the city for something better. Eger was counsellor to the Roman king Numa Pompilius. The satisfaction of a humane retreat was a theme of Ovid (Metamorphoses, III), Livy, Philip Sidney in Arcadia, Horace and many others.

Pope’s gardener’s account of the materials of the grotto (1745) included ‘a fine piece of Marble from the Grotto of Egeria near Rome, from the Reverend Mr. Spence’.

A Twickenham restoration is to be looked forward to.