Paradoxes of Planetary Defence

Tom Stevenson

In 1908, an asteroid struck Siberia with more explosive force than most nuclear bombs. Travelling at thirty thousand miles per hour, it crashed through the atmosphere and burst into a fireball above Krasnoyarsk Krai, flattening two thousand square kilometres of forest. In a number of ways this was fortunate. Had the asteroid instead hit a major city – London, say, with a population of seven million, or St Petersburg, population 1.5 million – the effects would have been devastating. Had it struck the same spot fifty years later it might have set off a nuclear war.

The argument that technologically advanced societies should try to do something to prevent future impacts seems reasonable, but in 1994 Carl Sagan and Steven Ostro wrote an article on the ‘dangers of asteroid deflection’. The most troubling was the paradox that developing the ability to deflect asteroids could increase the probability of an asteroid striking the Earth. ‘If we can perturb an asteroid out of impact trajectory,’ Sagan and Ostro wrote, ‘it follows that we can also transform one on a benign trajectory into an Earth-impactor.’

Intentionally causing an asteroid to strike the earth might sound preposterous, but powerful states deal in the preposterous. And what if a major state were overtaken by millenarian ideology? Or an asteroid deflection intended for some benign purpose went badly wrong? Large asteroids on trajectories that coincide with Earth are very rare, but the ability to deflect asteroids would always be subject to ‘well-established human frailty and fallibility’ and had the potential, in Sagan and Ostro’s view, to become a ‘category of danger that dwarfs that posed by the objects themselves’.

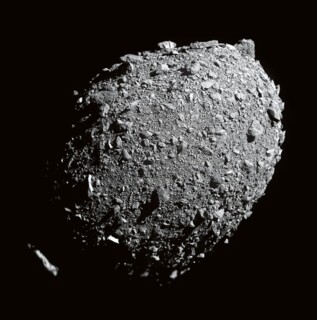

On 26 September 2022, Nasa completed its first asteroid deflection test (Chris Lintott wrote about it in the LRB at the time). The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (Dart) spacecraft launched from Vanderberg Space Force base in Santa Barbara, California. It travelled for ten months at a speed of 22,000 kilometres per hour before slamming into Dimorphos, a small asteroid in orbit around another, larger asteroid named Didymos. Dart was only about two metres across, not counting its two 8.5-metre solar arrays sticking out like wings, but it was big enough to knock the 150-metre wide Dimorphos off course. (The size of the Siberia asteroid isn’t known with certainty but it is thought to have been around the fifty-metre mark. The Chicxulub impactor which wiped out the dinosaurs was fifteen kilometres across.)

The test was judged a complete success. A series of articles published by Nature in April laid out the details, and said that Dart had demonstrated asteroid deflection ‘at size and velocity scales relevant to planetary defence’. In fact it exceeded expectations. The force of the kinetic impact alone was thought to be enough to alter the orbit of Dimorphos by seven minutes, knocking it closer to Didymos. But the ejecta created by Dart’s impact transferred so much momentum to the asteroid that Dimorphos was knocked closer to 33 minutes off its orbit. The descriptions in Nature were unequivocal: Dart showed ‘the viability of kinetic impactor technology’.

In his book Dark Skies, published in 2020, Daniel Deudney argued that planetary defence against asteroids was worth the risks. But he also said that asteroid cartography and diversion should be the preserve of a consortium of ‘the leading states on earth’. He wasn’t clear about who would be in the consortium. I imagine he had the US and its allies, and perhaps Russia and China, in mind. Now that the technology exists, the question of who should wield it presents itself again.

Asteroid deflection contains many impulses. There’s experimentation but also catastrophism, and something of natural awe. The more one looks at the universe, the more one can feel, as Pliny did, that ‘it really exceeds all other wonders that one single day should pass in which everything is not consumed.’

The fact that Nasa has a Planetary Defence Co-ordination Office would seem to be evidence of planning for natural hazards, of the drive to protect against mass extinction, perhaps even an expression of planetary conscience. But there is also the context of space militarisation. Armed forces depend on space capabilities more than ever before. And who now remembers the Sagan-Ostro paradox? No asteroids have been detected that pose a real risk of colliding with the Earth in the next century or so. On their current courses, at least.

Comments