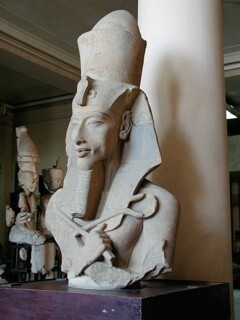

Akhenaten in Ankara

Ayşe Zarakol

The earthquakes that hit Turkey and Syria on Monday, 6 February have officially claimed more than forty thousand lives, though the final tally is expected to be many times that already shocking number. Even more are injured. Whole cities lie in ruins, their populations displaced, perhaps for ever.

Some commentators argue that this disaster will spell the end of Erdoğan’s regime, already weakened by Turkey’s prolonged economic crisis. Even with all the news media under his control, the president may not be able to control the narrative this time, they say: the damage is too vast, the corruption too obvious, the pain too deep and widespread.

The palace does seem afraid. When the immediate calls not to politicise ‘the disaster of the century’, ‘fate’, ‘Allah’s plan’ etc. didn’t work, the president’s social media henchmen started spreading conspiracy theories, accusing anyone who criticised the government response of being an opposition plant, and fanning fears about looting and refugees in an attempt to divert public anger.

Now there are talks of delaying the presidential election, originally slated for May and required by the constitution to take place before mid-June. It isn’t unimaginable that it will be postponed beyond the constitutional deadline. And once that has been done, the election is unlikely to happen at all. There will always be another justification for postponement. Turkey never lacks for crises.

Whatever the short-term outcome, though, these earthquakes will permanently stain Erdoğan’s one-man rule. Politicians in all types of regime, including democracies, are put to the test by emergencies and the way they handle them. Boris Johnson might still be prime minister were it not for the lockdown parties at Number Ten. Hurricane Katrina was the beginning of the unravelling of George W. Bush’s popularity. But throughout history, it has been the strongmen, the tyrants, the centralisers who are most damned for posterity by their failure in the face of natural disaster.

Amenhotep IV, pharaoh from 1353 to 1336 BCE, made the ultimate power grab a few years into his reign. He claimed the old gods were no more and everyone would now have to worship Aten, the sun disc (previously an aspect of Ra). The pharaoh took a new name, Akhenaten (‘beneficial to Aten’), and built a new capital, Akhetaten (later Amarna), dedicated to his new religion. Aten did not have the anthropomorphic qualities of other Egyptian deities, but was merely a light that shone on and through Akhenaten.

Akhenaten is sometimes credited with inventing monotheism, but I think of him rather as the first extreme political centraliser. The Ancient Egyptian state was already organised in such a way that there were very few checks on pharaonic power; they were already deified. But polytheism meant the pharaoh could only be one among many. By eliminating all the other gods in the name of an abstract sun disc whose cult could only be mediated through himself, Akhenaten was essentially trying to centralise all authority – both political and religious – in his person only.

What Erdoğan has attempted in Turkey, more than three thousand years later, follows the same pattern. The Turkish state was already centralised, but Erdoğan has centralised it even further around his person. No state institution now has any autonomy or ability to check the presidency. Ruling often by decree, he decides everything from foreign policy to everyday mores. In practice he may be weaker than he seems (most centralisers are) but the space he symbolically occupies is not that different from Akhenaten’s. L’état, c’est lui.

The problem with trying to make yourself a god on earth, however, is that awesome powers need awesome justifications. Divine kings across the ages were tasked with maintaining life’s balance, controlling nature, conquering the world: immortal feats are naturally expected from those who claim they are better than mere mortals. And the stronger the bid for centralisation, the higher the expectations. A largescale natural disaster breaks the spell and reveals the ruler to be a lot less than he claims to be. There are realms beyond his control. He too is human. Worse, he may in fact be responsible because of his delusions of grandeur.

The story did not end well for Akhenaten. He ruled for seventeen years, which probably seemed interminably long to his subjects, but was a mere blip in Egyptian history. After a while he was completely forgotten. His religion and capital city were abandoned after his death. His monuments were dismantled, his statues destroyed and his name excised from the list of kings. The final years of his reign were beset by severe crises, including a plague. Akhenaten’s successor, Tutankhamun, had this period of despair recorded for posterity: ‘The land was in grave ailment, the gods had turned their backs on this land.’

Erdoğan’s supporters now ask whether it is fair for one man to be held responsible for the devastation caused by earthquakes of such magnitude. But they too must know that Erdoğan cannot have it both ways. Either he is an extraordinary person who deserves his extraordinary powers or he is an ordinary person playing god on earth. The only way out is for the ordinary people of Turkey to reclaim their agency.

Comments