In the City of the Dead

Amir-Hussein Radjy

Ramadan has lived in the tomb of Ratib Pasha, Egypt’s late-19th-century army chief, since he was born. The large chamber of floriated stone, honeycombed walls and coffered ceilings is an example of an Egyptian style of architecture that draws on Ottoman, European and Mamluk elements. But it is marked for demolition, along with thousands of other tombs in the Qarafa, Cairo’s centuries-old City of the Dead, to make way for new roads. The guardian of the tomb opposite, Ramadan showed me, had erased the black arrows that marked it for bulldozing. ‘He thinks that’ll make a difference,’ he laughed.

Earlier that day, we had set out to survey the destruction. I was shocked by its scale. The City of the Dead is a vast, 1300-year-old necropolis, that stretches for ten kilometres along the eastern edge of old Cairo. It hosts the shrines of some of Islam’s most important figures as well as the tombs of Egypt’s sultans and 19th-century rulers. The government says the demolitions won’t touch monuments that are registered antiquities under Egyptian law. But Ratib Pasha’s tomb and many other historical and family graves will be lost. The area is also home to thousands of living people who are being evicted.

We had begun our visit near the shrine of al-Suyuti in the southern cemetery. The friend I came with parked his car in a nearby lane planted with jacarandas and ficus. A gardener was irrigating the hedges. Chickens clucked in a yard.

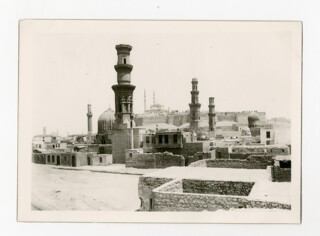

We turned the corner to confront a scene of destruction. The view of the ‘Tombs of the Mamluks’, a group of 14th-century minarets with Saladin’s citadel rising behind, was a popular subject for early photographers in Egypt, including Flaubert’s companion, Maxime du Camp, who took perhaps the first calotypes of the tombs. It was now unrecognisable. A swath had been cleared in front of al-Suyuti’s squat white dome. At the base of the bulb-capped Sultaniyya minaret, the excavators clawed open dozens of new and old crypts. There was the thud of stone breaking. Piles of rubble dwarfed the labourers. Backing away, I stumbled over half a skull. To the north, the bright orange flowers of the flame trees stood out in the ruins.

I later spoke with the architect Galila El Kadi, who said the demolitions in the Qarafa and nearby historical areas were ‘unthinkable’. El Kadi was a key figure in persuading the authorities in the 1980s and 1990s to drop plans for developing the necropolis, although its size and location mean it’s a prime target for city planners. ‘We thought with all these laws and regulations, no one would dare touch the cemeteries,’ El Kadi told me. She estimates that more than 150,000 tombs have already been cleared in the past few years, during a first wave of state-ordered demolitions. Many heritage workers say that all there is left to do is document the site, and make a full record of what is being lost.

Egyptian officials say the development projects will boost tourism. They also cite the thousands of people living in the tombs, and the tenements that have spread into the cemetery, as a pretext for clearing the area and creating a cordon sanitaire around its principal sites. But the City of the Dead is more than the history of its monuments. It has always been a living city. The medieval chronicler Maqrizi wrote that the Qarafa was ‘where two worlds meet, that of life and that of beyond’. At night, the cemeteries were filled with the prayers of hermits, as well as ‘revellers’ out to take the desert air and make music. The great funeral complexes included markets, schools, libraries and residential blocks. Photographs taken by Gabriel Lekegian in the late 19th century show new houses among the tombs, many of them with wooden jalousies and stone doorframes.

It is difficult to imagine the shape of the city without its Qarafa. The novels of Naguib Mahfouz and Khairy Shalaby, the films of Youssef Chahine and, more recently, Iman Mersal’s book Traces of Enayat return, time and again, to the necropolis. Chahine’s Le Sixième Jour, a sprawling film about the postwar city, depicts the cemetery as the home of honourable thieves, holy fools and raucous enchantment. These stories romanticise the cemetery’s living society. But I have met clerics and civil servants who live in the necropolis, along with the turrabi or gravediggers who know where the bodies are buried: there is no full official registry. The guardian of Ratib Pasha’s tomb is a plumber. In the northern cemetery you can see the grave of Hassan El Arabesque, a prosperous glassblower. His son, a textbook editor, lives in a nearby tomb.

The prime minister has said the government’s plans will make Cairo ‘civilised’ again. Key planning decisions, including new highways ripping through the old town and the removal of historical houseboats along the Nile, have fallen to the army engineering corps. Many people are having trouble coming to terms with the scale of changes. But the loss of family crypts, some of which have been used for more than three centuries, has provoked shock. Many of the tombs are maintained by family awqaf or endowments that should be protected under Islamic law. The head of one aristocratic family told me he couldn’t understand what the authorities were doing, unless they had no respect for ‘our identity and wanting people to remember who they are’.

On my last walk in the cemetery, I visited the grave of Ali Pasha Mubarak, the minister of public works who oversaw Cairo’s rebuilding in the 1870s in the image of Haussmann’s Paris. The pasha’s great-great-grandson, Gaber, showed me the tomb. The headstone of the family patriarch is capped with a marble tarbush, a symbol of the rank the pasha achieved though he was born in poverty. Gaber said the authorities aren’t developing the city, but destroying it. ‘What are they talking about?’ he said. ‘Development has nothing to do with the graves. There are other solutions if they want more highways.’

Gaber buried his mother and grandmother in the crypt. He lives more than an hour’s bus ride away, near El Marj, but visits regularly. He says the family has refused to comply with demolition orders, although the surrounding mausolea are rubble already.

Comments

Such a beautiful, evocative post.