Skiddy Corners

Clare Bucknell

Eight years ago I wrote about competing in the women’s Real Tennis World Championships. I’d been playing the sport for less than three years, which is nothing (players seem to hit their stride around late middle age), and the Worlds was my first major competition. I was enthusiastic but distinctly weirded out. I had questions. Did other competitors think hitting a hand-sewn ball into a netted gallery adorned with a tiny silver bell was normal? Did they like their clubrooms to be decorated with oil paintings of exclusively trousered Victorian competitors? And what was with all the polo shirts embroidered with references to sporting societies I’d never heard of?

Stockholm syndrome is a powerful thing. In the intervening years, things got real, fast. I acquired all the polo shirts I could. I joined the Brigands Tennis Club. I joined the Jesters Club. I played tennis in a gated village in upstate New York and in a former goldrush town in Victoria. I became a Friend of Hardwick House, a country estate with attached tennis court, supposed to have been the inspiration for Toad Hall. When you play at Hardwick, the clubroom is so cold you have to begin by switching on a parade of storage heaters and lighting the fire in the grate. The last time I visited, someone had stuck pink Post-it notes to each of the external doors: ‘Please keep door shut or birds fly in.’ During our match a pigeon entered and flapped about in the rafters.

Earlier this month, the Worlds took place in Britain for the first time since 2015. Back then, the tournament had been held in Leamington, at the world’s oldest private members’ tennis club. This time it was at the Oratory School, a Catholic private school in the Oxfordshire countryside. As a tennis newbie, I’d felt unable (and unwilling) to join in the other players’ hushed conversations about what made Leamington a good or bad court. This year I was all for it. Nothing about my game, it turned out, was helped by knowing that the Oratory was bouncier than average and had ‘skiddy corners’. The far superior players who beat me were always going to beat me.

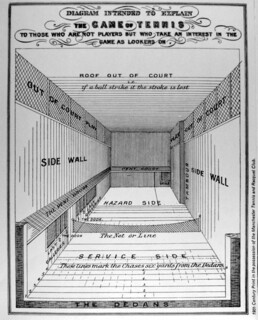

As my friend Sophie once pointed out, ‘real tennis’ is a good example of a retronym, a new name invented from an old one in order to adapt to technological advancement. Until the game we know as ‘tennis’ (or ‘lawn tennis’) came along, real tennis was tennis. Then, when playing on larger courts outdoors became fashionable, it turned into real tennis, an odd, disinherited elder sibling. Over the last two centuries, through occasional moments in the sun and long stretches in the dark, it has thrived on being a bit weird, a bit rebarbative, sticking two fingers up to change.

Many people who love it fear that its survival will mean the loss of the things that are most distinctive about it. Sure, the wooden racket is heavy, unwieldy and has a minuscule sweet spot, but wouldn’t playing with a graphite one spoil the fun? A bad workman blames his tools, and real tennis, with its old-fashioned equipment, uneven, hand-stitched balls and idiosyncratic playing surfaces, gives you a lot of scope for that.

What is changing rapidly, and apparently with little pushback, is the game’s visibility. Real tennis has always been a spectator sport. One of the galleries into which you hit the ball to score a point, the ‘dedans’, is also a seating area for viewers. Everyone likes being applauded for a good shot, largely because it’s so stupidly difficult. Now, social media is delivering applause in the form of comments and emojis. At the Oratory, play was filmed by several cameras simultaneously to produce a stream for YouTube, with stats graphics and voiceover commentary. Photos and scores were uploaded to Instagram. In the commentary ‘box’ there was semi-joking talk of setting up a VAR system for tight calls. A sport in love with its past is looking almost futuristic. I’ll report back again in 2031 to let you know how it’s going.