Freud’s Milton

Joe Moshenska

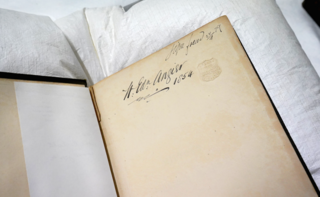

Unlike her father’s consulting room, which has been preserved as the centrepiece of the Freud Museum in Hampstead, the room in which Anna Freud saw patients is now one of the museum’s administrative offices. When I was there last month, a member of staff showed me a book I hadn’t been expecting to see: Sigmund Freud’s copy of John Milton’s poetry, in two volumes, each inscribed with Freud’s signature.

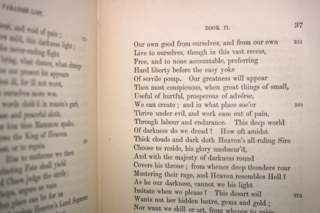

I felt rather embarrassed that, having spent some years thinking about connections between the two writers, I hadn’t thought to ask whether Freud’s copy of Milton survived. I wanted to hold it but that wasn’t allowed, perhaps aptly – Milton and Freud are among the writers most preoccupied with forms of prohibition. I was, though, able to look at the photos that an archivist had taken of the only marks to be found in the volumes: as well as Freud’s signature above the name of an earlier owner, there was a single faint pen or pencil mark alongside six lines in the second book of Paradise Lost.

They are spoken by Mammon, part of his contribution to the fallen angels’ debate about how best to respond to the failure of their rebellion against God. Milton writes of Mammon that ‘even in Heaven his looks and thoughts/Were always downward bent,’ fixated on the golden pavements rather than divine glory. Mammon argues against further conflict with God, suggesting instead that the fallen angels should focus on beautifying their new surroundings with ‘gems and gold’:

Our greatness will appear

Then most conspicuous, when great things of small,

Useful of hurtful, prosperous of advérse,

We can create; and in what place soe’er

Thrive under evil, and work ease out of pain

Through labour and endurance.

These are the lines that Freud seems to have annotated. It’s always difficult to know how much weight to place on marginalia of this sort – whether it indicates passing or serious interest – and the question is both more tantalising and more vexed when it comes to Freud. His interest in gold – especially as a symbol of human faeces – is well known, and in ‘Character and Anal Eroticism’ he wrote: ‘We know that the gold which the devil gives his paramours turns into excrement after his departure … Indeed, even according to ancient Babylonian doctrine gold is “the faeces of Hell” (Mammon = ilu manman).’ Freud might have been struck by the passage in Paradise Lost because it brought him back to a figure involved in a series of substitutions and transformations – words, gold, shit – that were of enduring interest to him.

If we do not flee quite so rapidly into the symbolic realm, however, and attend not only to the significance of the speaker but to the possible resonance of the words themselves, then Mammon’s plea for the fallen angels to beautify Hell sounds remarkably like the aim of psychoanalysis. To ‘work ease out of pain’ is the purpose of many therapeutic approaches, from Socrates to contemporary self-help books. But to create ‘great things of small,/Useful of hurtful’, sounds more specifically psychoanalytic: hurt is not to be recovered from, or left behind; our formative lacerations are not simply to be got over; hurt is itself useful for creation. And the route to these possibilities involves making ‘great things of small’, just as Freud would attend not to abstract questions or to character types but to the smallest, slipperiest, most incidental parts of experience: slips of the tongue, shards and flashes of our dreamscapes.

I had gone to the Freud Museum to discuss the relationship between the two writers with Adam Phillips, and in the course of our conversation he read to me from a letter that Freud wrote to his fiancée a few years after buying his copy of Milton, in which he described feeling ‘completely at a loss how to find the necessary sympathy and attentiveness’ to engage with a patient: ‘I felt so limp and apathetic.’ Eventually Freud dragged himself from his torpor and achieved the necessary ‘awareness of calm preparedness’ – ‘a mood’, he said, ‘for which an even greater poet [than Goethe] found the loftiest expression with the words:

Let us consult

What reinforcement we may gain from hope,

If not, what resolution from despair.’

This is, rather wonderfully, a slight misquotation. The words ‘Let us consult’ appear nowhere in Milton’s poem, and Freud has brought the verb down from a few lines earlier. A tactical tweak for the sake of clarity? The deliberate mixing of Milton’s words with his own invented ones? Or a Freudian slip?

If there is awkwardness in the way Freud adapts these lines, it perhaps reflects the fact that, though he attributes this ‘loftiest expression’ to Milton himself, Milton puts the words in Satan’s mouth, when he is seeking to rouse himself and his troops in the poem’s opening book. The sentiment is similar to the one expressed by Mammon in the lines that Freud annotated: let us gain resolution from despair; let us work ease out of pain. But – as with the feeling that Mammon’s words anticipate psychoanalysis – it is easier to assimilate the phrase when it’s read as Milton’s own, evading the thorny question of how we are to respond to compelling claims that emerge from the mouths of devils.

I found myself hoping that a single pen mark might give me a definitive answer to a question I had been asking for a while: what, in Milton, mattered to Freud? At the same time, I was suspicious of the impulse to know for sure – to crack the code once and for all. Freud himself was divided between a desire to develop a science of the human psyche – to be an expert in the unconscious – and an awareness that such an ambition is doomed, since the unconscious thwarts our claims to be experts in anything, least of all ourselves. Milton was torn in a different but comparable way between a powerful sense of his specialness – of his intellect, will and prophetic insight – and a realisation that understanding was always dependent on forces beyond his control, an unending project rather than a settled state.

Aligning the two writers across the fulcrum of this single annotation, this spectral stroke of the pen, brings newly into focus their paired forms of striving for and flinching from certainty. The annotation itself is charged with uncertainty: Freud was the second owner of the book, and there’s no way of knowing for sure that his pen drew the line. But this redeems it from a certainty that would close questions down, and instead allows them to multiply. Are we to read the demonic words and the faint line accompanying them as expressions of a mind sure of itself, confident of the parts that matter – whether parts of a poem, or of a life? Or are they symptoms of a mind desperately searching for certainty, using words that glimmer with possibility like the gems and gold of hell, but turn out to be little more than fragments to be shored against our ruin? The answer, as ever, is both at once, whether the mind is Satan’s, Mammon’s, Milton’s or Freud’s.

Comments

Then most conspicuous, when great things of small,

Useful of hurtful, prosperous of advérse,

We can create; and in what place soe’er

Thrive under evil, and work ease out of pain

Through labour and endurance.

Doesn't this describe Brexit?

and in itself/ Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven." Genau!!!