In the Brontë Machine

Helen Charman

Emily, written and directed by Frances O’Connor, is a ‘speculative biopic’: a heavily altered version of Emily Brontë’s life, centred on an imaginary relationship with William Weightman, her father’s curate at Haworth from 1839 until his death from cholera in 1842. There is some historical evidence to suggest that Weightman had a relationship with the youngest Brontë sister, Anne; but O’Connor’s film goes with feeling – some people find it difficult to believe that a virgin could have written Wuthering Heights – rather than fact. In interviews, O’Connor has defended her decision, which I think is interesting, through the lens of popular feminism, which I think is not: ‘There’s always a gap between who women really are and who they’re supposed to be.’

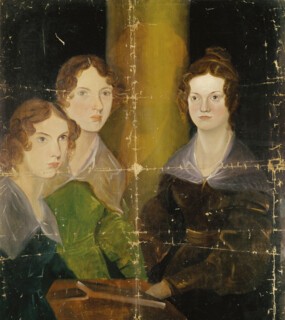

Interest in the lives of the Brontë sisters – in who they ‘really’ were – is seemingly inexhaustible, fuelled in part by frequent adaptations of their most popular works. O’Connor’s movie, which contains multiple references to the visual motifs of Wuthering Heights (a face at the window, a white nightdress, an impassioned ghost in the night), is beautifully filmed, with a compelling central performance from Emma Mackey; still, it’s difficult to watch without a sense of déjà vu. It’s hard to take seriously a scene in which a woman in a corset sits down at a desk, takes up her quill, and spells out the title of one of the most famous novels in the world.

Admittedly, I may be too easily inclined to feeling like a cog in the Brontë machine. Over the past six years, I’ve taught various Victorian literature modules at many different British universities, always on short-term or hourly-paid ‘teaching track’ contracts (i.e. no research). It doesn’t matter what your specialisms are: if you’re a Victorianist with a heavy teaching load, especially if your work relates even tangentially to gender, you’ll spend a lot of time marking essays on Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and ‘strong female characters’. This is frequently a pleasure: discussing the novels with students often reveals something real among the overdetermination, helps me see the texts clearly again. The fact remains, however, that I neither chose nor expected to devote quite so much of my working life to the Brontës, and yet here I am. They got me.

I approached Emily as a teacher: I went to see the film in part because I thought my students would probably see it and I wanted to be able to talk about it with them. Coincidentally, I saw it on the day that the Universities and Colleges Union released their latest ballot results, in which members voted overwhelmingly in favour of continuing our multiple ongoing disputes, including one over the working conditions of precariously employed members and those who, like me, are contracted only for a short time, and whose labour adapts, chameleon-like, to pre-existing timetables and reading lists. Most of the responses to Emily have focused on sex and death; nobody told me it was a film that hates teaching.

In an early scene, a feral Emily returns from the moors to greet Charlotte, back from Roe Head Girls’ School and transformed into a lady: ‘Is that you in there?’ Emily asks her, as the sisters struggle to re-establish their previous intimacy. Charlotte is portrayed as a woman who has put away childish things, preferring bourgeois structure to telling stories with her sisters; she has ‘no time’ to write, she boasts, or even to dream: on a teacher’s schedule, dreaming is ‘a waste of good sleep’.

Emily tries to follow in Charlotte’s footsteps, but her experience at Roe Head is a calamity: a fish out of water, extremely homesick, she ‘shrivels up and dies’. O’Connor represents this rejection of teaching as the spur for serious emotional and creative development: home again, Emily runs riot with her brother Branwell and adopts a joint creed, ‘freedom in thought’. She writes poetry and – crucially – falls in love with Weightman. Heartbroken after he rejects her, she decides to study and teach alongside Charlotte in Brussels, and declares that she will no longer write.

In the movie’s version of Charlotte, so entirely in the thrall of convention, I can’t recognise the writer of Jane Eyre and Villette: O’Connor alters the chronology to suggest that Charlotte only began to write novels after Emily’s death. (In fact, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights were published the same year.) All three Brontë sisters had complex, ambivalent relationships with formal education, and both Anne and Charlotte drew on their traumatic, humiliating experiences working as governesses for their fiction. Emily suffered badly from homesickness at Roe Head and at a later teaching position in Halifax, but teaching remained a goal: the sisters intended to open a school, ‘The Misses Brontë’s Establishment for the Board and Education of a limited number of Young Ladies’, at Haworth, abandoned for lack of pupils and funding in 1844.

It wasn’t teaching that was the enemy of freedom or thought for Emily, but rather the institutions in which she had to work, an experience shared by her sisters, even if they were more resilient. Still, the appeal of feeling persists. The stifling school corridors of Emily are an easy image to set up as the opposite to what counts, in O’Connor’s terms, as Emily’s ‘real’ life: the freedom of the moors, writing late into the night, sex. These are the images that have compressed the Brontës into a recognisable and strangely impenetrable commodity.