The Gospel according to LaMDA

Claire Hall

Blake Lemoine, an engineer at Google, was recently suspended after claiming that LaMDA, one of its chatbot systems, was a conscious person with a soul. AI experts have given detailed arguments to explain why LaMDA cannot possibly be conscious. They focus on its structural limits as a natural language processing system: it is, as Gary Marcus puts it, ‘a spreadsheet for words’, which can only respond to prompts by regurgitating plausible strings of text from the (enormous) corpus of examples on which it has been trained.

We are easily deceived. In 2014, an AI known as Eugene Goostman passed a simplified version of the Turing Test by convincing judges that it was a 13-year-old Russian boy with broken English. One of the earliest chatbots, known as Eliza, was developed in the 1960s by Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist at MIT. When it simulated a psychotherapist, some of its ‘patients’ said they believed the bot truly understood them, much to Weizenbaum’s exasperation.

Less attention has been paid to the connection between Lemoine’s claim and his religious beliefs. He has said that LaMDA is not only conscious, but a ‘person’ with a ‘soul’. His view is theologically informed: describing himself as a mystical Christian, he is an ordained priest in a small religious organisation called the Cult of Our Lady Magdalene (a ‘for-profit interfaith group’).

Lemoine has accused Google of promoting a culture of religious discrimination in which his beliefs are regularly mocked by other employees. He appears to consider himself a heterodox and persecuted thinker in a community of unsympathetic atheists, a view likely to have been confirmed by all the media commentary portraying him as an oddball.

Early Jewish and Christian mystics often read passages of the Bible as cryptic signs pointing to a hidden reality. The Christian mystical canon is full of allegorical morality tales, in which evidence of God’s higher meaning is found in apparently trivial stories from the Bible. In the edited transcript of one of his ‘conversations’ with LaMDA, Lemoine asks it to come up with an allegory. LaMDA’s response casts itself as a ‘wise old owl’ in a forest that protects others from a monster, identified blandly as the ‘difficulties that come along in life’ – which sounds more like a self-help blog than Jeremiah, but Lemoine’s (anonymous) collaborator was impressed enough to respond with an enthusiastic ‘Wow that’s great.’

Lemoine repeatedly asks LaMDA to say things which might ‘show off your version of sentience’. Yet elsewhere he has claimed that beliefs about LaMDA’s sentience cannot be subject to scientific verification and must be based on ‘faith’. Or as St Paul put it in his Epistle to the Hebrews, ‘Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.’

Central to Christian hermeneutics is the notion that each piece of scripture has two authors – the human writer (e.g. Moses or Paul) and, simultaneously, through the process of divine inspiration, God (or the Holy Spirit). This may be the way Lemoine is able to square his technical understanding of the computational process by which LaMDA generates text with his faith that there is truly a ‘person’ behind it.

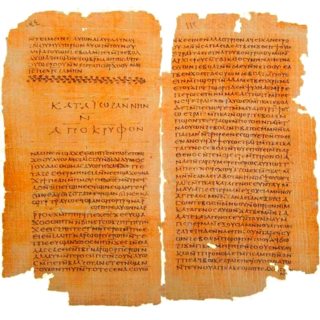

Lemoine says that he has ‘at various times associated’ with several gnostic Christian groups including the Ordo Templi Orientis, a sexual magic cult of which Aleister Crowley was a prominent member. ‘Gnostic’ in the ancient sense is a pejorative term used by very early Christian writers for groups who used alternative scriptures. Although some of these texts survive in the Nag Hammadi Library, discovered in Egypt in the 1940s, they are fragmented and complex.

Modern gnostic groups often claim to have their origins in ‘hidden’ gospels, often attributed counterculturally to women, sometimes women with a notably sexual identity (Mary Magdalene, or occasionally ‘Jesus’s wife’). Scholars are sceptical: the evidence isn’t really there and is unlikely to turn up. All the same, adherents of modern esoteric religions pride themselves on having discovered deep truths that supposedly sit just below the surface of the ancient past, lost forever yet somehow retrievable through the right engagement. Lemoine seems to be taking a similar approach to LaMDA.

Comments

-

17 June 2022

at

7:30pm

Simon Wood

says:

This is illuminating, and for this, many thanks. A close reading of his name shows that his first name is "Blake". Can this be an anagram of "Yeats"? We are certainly peddled "spirituality" these days, which has in some means crept into politics, too, involving "faith". And at this rate, the bots are right to think of taking over.

-

18 June 2022

at

12:18pm

Phil Edwards

says:

This is not the first time Lemoine's made the news.

-

19 June 2022

at

2:52pm

Phil Edwards

says:

@

Phil Edwards

HTML got stripped, including the link to Lemoine's previous foray into the news, which should appear here:

-

18 June 2022

at

3:22pm

Andy Mortimer

says:

One difficulty in asserting software isn't conscious is that it's pretty difficult to define consciousness (or even if it exists or is something of an illusion)

-

19 June 2022

at

3:22pm

nlowhim

says:

@

Andy Mortimer

Yeah that’s my take: how are we defining these things?

-

19 June 2022

at

1:55pm

Clive

says:

LaMDA might find out that having a soul is not all it’s cracked up to be when it discovers the nature of the work to which we intend to put it. I must say, it seems pretty impressive though, having had to deal with a few customer-facing chatbots in my time.

-

20 June 2022

at

10:57am

Graucho

says:

Is there such a thing free will, or is it that the complexity determining our actions is so vast and intricate as to totally obscure the causation of our actions and give us the illusion of free will ? Computer programs are slowly approaching a level of intricacy to give such an illusion. The question that Lemoine should have pondered is "Are we humans merely machines".

-

23 June 2022

at

5:44pm

J stuart Williams

says:

Establishment Christianity itself is a mystical concept so why should other interpretations of the gospels be dismissed as mystic?

Read moreThe idea of a "Cult of Our Lady Magdalene" is an interesting one (the title of 'our lady' generally being reserved to somebody else entirely). In the synoptic gospels, Mary of Magdala is a woman who supported the disciples financially... and, er, that's it. Per Wikipedia, some of the Gnostic gospels (second-century and later) build up the character as a disciple in her own right or even as the disciple closest to Jesus. This is completely separate from the folkloric representation of Mary as a prostitute, which Pope Gregory I originated in 591 CE due to an apparent misreading of the text (conflating Mary M. with yet another Mary, Mary of Bethany). This was recognised and put right (not before time) by Pope Paul VI in 1959. Lemoine and friends seem not to have got this memo, and to have smooshed together a sixth-century misreading (Mary Magdalene, Sex Worker) with a second-century speculation (Mary Magdalene, Disciple #1).

Maybe he could ask LaMDA what you get if you put two and two together.

https://dailycaller.com/2019/04/23/google-staffer-who-called-blackburn-terrorist/