In Fishguard

Gillian Darley

Suspicions of invasion come in many guises, but the first sighting of four French vessels off Lundy Island, clearly signalling their intentions by the names of the two frigates, La Vengeance and La Resistance, presaged serious alarm. The last hostile invasion of mainland Britain took place in south-west Wales on 22 February 1797. The French revolutionary force, led by an Irish-American colonel, William Tate, were captured two days later. The initial plan had been a three-pronged attempt to liberate Ireland but various misadventures meant that the landing of a rump force in Pembrokeshire, planned as a distraction, was all there was to be – a disconsolate arrival on the wrong island.

The local Volunteers easily took advantage of the invaders, who had been further incapacitated by falling on generous stashes of liquor – some for an imminent wedding party, some smugglers’ goods. The local men were quickly relieved by the arrival of troops and within two days the commanding officers had met to negotiate a surrender on Goodwick Sands, close to Fishguard.

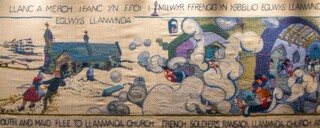

For the bicentenary in 1997, the Fishguard Arts Society made a tapestry on the model of the one in Bayeux. With scintillating detail and remarkable wit, the embroidery – thirty metres long and stitched by more than seventy local women – interweaves the stories told by the locals with those of the invaders.

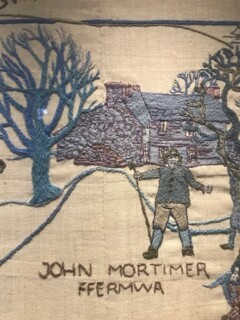

The presiding genius was a local artist, Elizabeth Cramp RWS, working with a team of three who guided the volunteers, aged from thirty to eighty, in the weeks, months and years it would take. In her own account of the process, she described how she had begun with details. Were Welsh Blacks already grazing the fields of West Wales in 1797? She found a ninety-year-old man whose grandfather spoke of red ‘Rowan’ cattle. She researched building materials and techniques, uniforms, horse harnesses, rigging (of the French ships), farm kitchens and more. Then she scripted forty scenes, later cut down to thirty-seven to accommodate the larger crowd scenes.

She went out to sketch the landscape and landmarks, ‘mostly in sunshine with gorse bushes in flower and smelling of honey’, and then began her task in earnest, drawing cartoons, first at quarter and then full size. These were then traced onto the stretched cloth for the stitchers to begin work. Cramp admired David Jones’s paintings and their intricacy comes together with her taste for the idiosyncratic to glorious effect. Her adviser on local history suggested she avoid myths, but she ‘tactfully forgot’ that guidance.

Colour matching, with Appleton’s vast range of crewel wools, was arduous but the grading and shading of tone, a broad-brush sense of rising drama (hot colours) set in a stony, pastoral landscape (cool colours) is one of the many glories of the work. It could be uncomfortable. One stitcher’s husband queried the green flesh-tones of a terrified French soldier, another was unhappy about an apparently purple horse. Allied to tone is texture, created by different kinds of stitch: nubbly tweed, variations of tree bark, boulder-built farmhouse walls. As at Bayeux, lettering (in Welsh and English) supplies dates, locations, identities.

The tapestry, one of the great community artistic endeavours of our time, is now owned by a trust and displayed to excellent effect in a purposely designed gallery in Fishguard Library.

Comments