Learn Everything from Stone

Percy Zvomuya

In the summer of 1990, Limit, a young Swiss pop rock band, were asked by their producer to back the Jamaican musician Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry for a one-night concert at the Bataclan in Paris. They had just one rehearsal in Zurich. Ever the professional madman, Perry mumbled some bewitching gibberish, lit a cigarette lighter with a huge flame, and chanted some raps. When the group arrived in Paris, Perry was still in Switzerland. He had missed his flight. By the time he eventually turned up to perform, the audience was getting restless.

‘We had no idea about reggae,’ Limit’s guitarist, Micha Lewinsky, told me. ‘I still have no idea about reggae. We had no idea who we were playing with.’ Perry was virtually unknown in Switzerland, where he had moved in 1989 with his Swiss partner, Mireille Ruegg. But he had also been largely forgotten in Jamaica, overtaken by new trends in digital or dancehall reggae, and moving to London after his studio in Kingston burned down in the early 1980s (he claimed to have torched it on purpose). For much of the late 1960s and 1970s, however, Perry had been at the centre of innovation in Jamaican music, through the transition from rocksteady to reggae; and his collaborations with the sound engineer and electronics genius King Tubby created dub, the forerunner of all modern-day dance music: jungle, techno, house, garage, dub step.

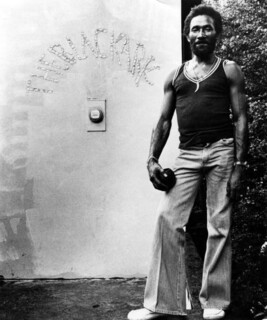

Perry, who died on 29 August at the age of 85, was born in Kendal, Hanover Parish, in the west of Jamaica. He worked first in the cane fields and then as a tractor driver on a road construction project in Negril. It was from the noise of rocks being broken up that he got his first ideas about music: ‘I learn everything from stone,’ he later said. In the sonic revolutions of dub, the human voice was stripped away, the drums and bass were accentuated and distorted, and non-musical sounds (such as gunshots) were added. Perry had no formal training in music or electronics, and his voice was not traditionally thought of as a singer’s. He went to Kingston and worked variously as a gofer, auditions supervisor, record promoter, songwriter and arranger, before opening his own studio, which he called the Black Ark, in his back garden. He didn’t play any instruments; the studio itself was his instrument.

One of his first hits was ‘People Funny Boy’, a jibe aimed at the producer Joe Gibbs, his former boss, whom he accused of exploitation. The 1968 track, featuring the cries of Perry’s baby, is an early diss track, now a staple of hip hop culture, and also an early example of sampling. If the song was a hit and brought Perry the kind of cash he had never had before, it also showed that the boundaries of popular music could be stretched beyond the limits set by music executives.

When Bob Marley returned from a stint in the United States in 1969, he moved in with Perry. It’s said Perry used to give Marley tea with honey to improve his voice. It was through Perry’s advice and production skills that Marley shook off his American influences and found his own voice. The songs produced by Perry, especially ‘Mr Brown’, ‘Soul Rebel’ and ‘Duppy Conqueror’, in which Marley was dipping into Afro-Caribbean mysticism, were a crucial phase in his growth and evolution; from there, he made the leap into Rastafarianism.

The Wailers fell out with Perry over his licensing of their music to a UK label without their knowledge, but he collaborated with Marley again in London in 1977 on the song ‘Punky Reggae Party’, which namechecked British punk bands including the Damned, the Clash, the Jam and Dr Feelgood. Perry worked with the Clash, too, producing ‘Complete Control’ for them. The collaboration helped bridge the gulf between Britain’s renegade sound and Jamaica’s, and to make the point that rebellion is rebellion, whatever its tempo.

Comments

Perry was one of those remarkable blue-collar autodidacts of immense talent. Seething energy, and some luck, propel them from the confines of the milieu that formed them bearing a singular vision. Think William Blake, if Blake had blazed eight ounces Lamb's Bread a day and pledged allegiance to Jah Rastafari. Perry's use of sonic space and understanding of the studio as instrument is reminiscent of another musical eccentric, Brian Eno, albeit in a very different vernacular.