Destination Peabody

Gillian Darley

In these interminable weeks, as Londoners – the lucky ones – take their circumscribed daily lockdown walks, Russell Square resembles a leafy prison yard, with the same faces passing again and again. When little enough in daily life is spontaneous, deciding whether to turn left or right outside the front door can provide a frisson of uncertainty. I find myself dipping into unfamiliar back streets or walking very much further than I’d intended. I never return by the same route. Yet a pattern has begun to establish itself: I go Peabodying.

In central London you’re never far from buildings designed by Henry Astley Darbishire, the dependable architect of choice for philanthropic individuals and institutions in the second half of the 19th century. His highest flight of fancy was the Gothic Revival hamlet of Holly Village in Highgate for Angela Burdett Coutts, as well as her Columbia Market (long gone), but the Maecenas of his career was George Peabody. Born in Massachusetts in 1795, Peabody made his first fortune as a dry goods merchant in Baltimore and moved to London in 1837, establishing the bank that would become J.P. Morgan the following year. His prodigious wealth and horror at the living conditions of the working poor in his adoptive city combined to transform the face of social housing.

Peabody died in 1869, soon after the first handful of estates came into being. Greenman Street, Islington, was the second Peabody estate to be built, in 1865, and with it Darbishire set a pattern. The high interlocked blocks, corseted into the pattern of existing streets, share a distinctive livery of striped brickwork, each block graced by a handsome entrance marked by a letter of the alphabet. But look closely at the different sites and you begin to spot the march of economy in Darbishire’s twenty-odd years of work. The port-hole windows and fancy brick brackets at attic level disappear, while the rear elevations become functional and unprepossessing. Yet the dignity of those surprisingly bold (and ubiquitous) lettered entrances was retained, a clear mark of respect for the tenants.

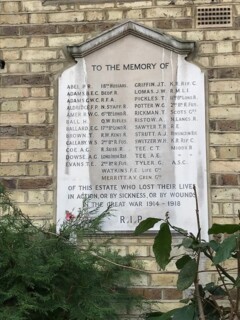

Many estates have been infilled (they suffered greatly from bombing in the Second World War), while others have been freed up with more outside space, but all have been refurbished to modern standards of space and convenience. There are play areas, seating and careful planting. The signage, usually in iron lettering, suggests considerable continuing pride. Some estates have war memorials. An occasional florid, Gothic ‘P’ is set into the brickwork, high up.

Abbey Orchard, a few steps from Westminster Abbey; Stamford Street, close to Blackfriars Bridge on the south bank; Whitecross Street, jostling towards the Barbican; the (to me) more familiar ones in Bloomsbury and Clerkenwell: the locations of early Peabody estates are an indicator of where the greatest pockets of poverty lay but also where there was employment. (Peabody tenants were not casual workers, unlike the vulnerable population that Octavia Hill and her colleagues tried to house and help.)

Secure tenancies are still passed down in families, after Peabody (and others) saw off a challenge in the 1980s, when changes in legislation threatened to throw their pattern of social housing onto the market bonfire . The estates remain integral to London and its life. Those who live on Wild Street, Covent Garden, as one long-term resident told me, are often relatives of those who worked in the market or had jobs in West End theatres. That continuity, expressed in architecture and underpinned socially, still feels like stability in the centre of a city where residential property is too often treated as a safe haven for global capital rather than for the people who need to live and work there.

Comments

Invaluable for finding jobs later, whether casual or permanent (remember them?)

How else would the vast number of more menial jobs the West End needs doing - at all hours of day or night -- get done?