San Gino

John Foot

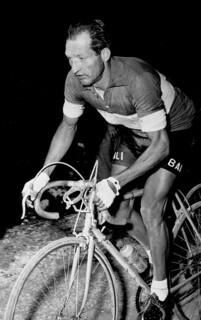

Gino Bartali was one of the greatest cyclists of all time, the ‘man of iron’ who just kept going, and going, especially uphill. In July 1948, as he won the Tour de France, his exploits were said to have prevented a revolution in Italy, where widespread protests had broken out over the shooting of the leader of the Communist Party in the centre of Rome.

Born in a small town near Florence in 1914, Bartali was a fervent Catholic; one of his nicknames was il pio, ‘the pious’. The Church adopted him as a non-Fascist symbol in the 1930s. He was revered by the Catholic base, and received personally by popes. Before the series of rides that took him to victory in 1948 in France, he had prayed at Lourdes. People claimed to have seen him flying up mountains borne by angel’s wings.

Around fifteen years ago, a story emerged about Bartali’s activities during the Nazi occupation of Italy. It was said that the great cyclist had saved dozens, perhaps hundreds, perhaps even thousands of Jewish lives, by cycling the eighty-odd miles between Florence, where he lived, and Assisi, a node in an underground network that helped to protect Jews, with forged documents hidden in his bicycle frame.

One of the main sources for the story was a priest called Padre Rufino Niccacci, in interviews for a book published in 1978 by the Polish writer and film director Alexander Ramati, who had been a war journalist in Italy. The book, first published in English, was described as a novel. Nobody made much of it or its claims for years, least of all Bartali himself, who died in 2000.

But then a former cyclist, Paolo Alberati, picked up on the tale in his university thesis, and it was aired again in a book in 2006. The story soon took off, embellished in books, newspapers and magazines. I repeated it in my history of Italian cycling, published in 2011. Plaques were put up celebrating Bartali’s bravery; a TV movie dramatised it; and in 2013 Bartali was named a ‘Righteous Gentile’ by the Holocaust Remembrance Centre (Yad Vashem) in Israel, leading to further memorialisation in Italy and elsewhere. There were calls for him to be made a saint and he was awarded a special medal by the Italian state. In 2018 the first three stages of the Giro d’Italia were held in Israel. During the race Bartali was posthumously made an honorary citizen of Israel after a special ceremony in which he was said to have saved the lives of eight hundred Jews during the Nazi occupation of Italy.

But in 2017 the first cracks in the myth had begun to appear. Michele Sarfatti, a leading historian of the Holocaust, pointed out some inconvenient facts in a trenchant article. There was no documentary evidence whatsoever, not a single piece of paper to link Bartali to the Assisi operation. And Ramati’s novel also made claims about the postwar mayor of Florence that could easily be shown to be false.

Sarfatti’s intervention was met with silence. The myth continued to be propagated. More monuments and plaques were unveiled. But now Stefano Pivato, a pioneering historian of Italian sport and culture, who has published widely on Bartali – and repeated the story about his heroics – has dramatically changed his mind. In a new book written with his son, Marco, Pivato argues that Bartali did not save hundreds of Jews. The whole story was made up. Pivato has asked time and again for the documentation that led to Bartali’s designation as a Righteous Gentile to be released to historians, but his requests have been refused. He also points out that in all the detailed research on Assisi during the war, Bartali’s name has never been mentioned.

Other stories of Italians saving Jews have also turned out to be problematic or exaggerated. Giovanni Palatucci was praised as a hero who saved hundreds (if not thousands) of Jews while working in the police service in Fiume. Streets and squares were named after him. The Church began the process of canonisation. The Primo Levi Centre argued, however, that not only were these claims untrue, but Palatucci appeared to have played a major and active part in the deportation of Jews from Fiume.

The reaction to Pivato’s book has been mixed. Some people are furious. Some have complained of antisemitism (a slightly ridiculous accusation if applied to Sarfatti, who is Jewish and has dedicated his professional life to research on the Holocaust in Italy). Many have defended Bartali, regardless of the actual facts of the case. Some of the claims about his heroics have been toned down, and the tales of the clandestine courier replaced with a more pedestrian account of his shielding Jews in Florence, although the details there, too, are unclear. But the general feeling is that nothing will change. Pivato’s book will be ignored. The Bartali myth will endure. He may yet be made a saint.