The Rolling Stone who stayed still

Alex Abramovich

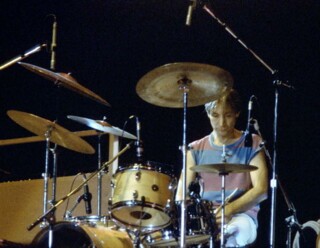

It must have been thirty or forty years ago, but I remember the clip vividly, as if I had watched it again and again in slow-motion – which I suppose I did in my mind’s eye. The camera pans across a stage and the drummer, completely immobile except for his hands, blinks slowly as it passes him by. The slightest gesture, but I had never seen anything so composed (cold-blooded, really), private (although it was a big stage, with thousands watching), and purposive.

Many years later, in an anthology edited by Luc Sante and Melissa Holbrook Pierson, I read Dave Hickey’s essay on Robert Mitchum, which quotes the actor at length:

A real gun is a very serious instrument. It has serious implications and terrible consequences, so you have to handle a gun like that, as if it were serious – as you would handle a very serious thing. If you do this, your character gets real in a hurry – your character steals the reality of the gun, which the audience already believes. On stage, it’s just the reverse. The setting and props are fake. Or even if they’re real, they look fake. So it’s a completely different thing. Also, the stage is still. When you’re acting in a film, you know that when people finally see what you’re doing, everything will be moving. There will be this hurricane of pictures swirling around you.

The projector will be rolling, the camera will be panning, the angle of shots will be changing, and the distance of the shots will be changing, and all these things have their own tempo, so you have to have a tempo, too. If you sit or stand or talk the way you do at home, you look silly on the screen, incoherent. On screen, you have to be purposive. You have to be moving or not moving. One or the other … A lot of times, in a complicated scene, the best thing to do is stand absolutely still, not moving a muscle. This would look very strange if you did it at the grocery store, but it looks OK on screen because the camera and the shots are moving around you.

Then, when you do move, even to pick up a teacup, you have to move at a speed. Everything you do has to have pace, and if you’re the lead in a picture, you want to have the pace, to set the pace, so all the other tempos accommodate themselves to yours.

I thought immediately of Charlie Watts – the Rolling Stone who stayed still as the hurricane swirled around him. Watts was dignified, in a world where dignity was never valued. Gifted, musically, in a way that none of the other Stones (Mick Taylor excepted) really were. Keith Richards had his heroin chic thing in place. Mick Jagger was more like cocaine: gimlet-eyed, fishy and gorgeous and hideous, taking himself very seriously, not being funny (qualities that applied to Brian Jones, too). But Watts gave the sense of someone who was in on the joke. In a smart piece about Exile on Main Street, Ben Ratliff quotes the Stones’ sometime producer, Don Was:

You’ve got five individuals feeling the beat in a different place. At some point, the centrifugal force of the rhythm no longer holds the band together. That [alternate take of] ‘Loving Cup’ is about the widest area you could have without the band falling apart.

That was all Charlie Watts’s doing. Like Robert Mitchum, he knew what it took to hold things together (which wasn’t the easiest thing in the world in his case, with Keith Richards running the musical show): as so often, it came down to the timing.

Comments

-

25 August 2021

at

3:32pm

Simon Wood

says:

That's an excellent example of what he did, that link to "alternate Loving Cup". I didn't really know who he was until yesterday - also quite an achievement, to be so anonymous.

-

25 August 2021

at

8:16pm

Fiona Reid

says:

You're too harsh on Keef. I'd say he's in the running for world's coolest rhythm guitarist- and those songs, wow!

-

25 August 2021

at

10:44pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Fiona Reid

I don't mean to be. I don't think he's talented, musically, in the way Mick or Charlie were, though I do think he's a hell of a writer. What I had in mind, specifically (and I'm certainly not the first to say this), is that in the Stones, the drummer followed the guitarist—not the other way around, as per usual—and this was especially difficult re. Keith's because he's always turning the beat around (something that's easy for a guitarist to do, but a lot less easy for a drummer to undo).

-

25 August 2021

at

10:44pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Fiona Reid

(Mick Jones, I mean to say, not Mick Jagger.)

-

25 August 2021

at

11:46pm

Eddie

says:

@

Alex Abramovich

In fact you mean Mick Taylor!

-

26 August 2021

at

1:22am

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Eddie

Thank you. It's been a long day!

-

26 August 2021

at

8:06am

Eddie

says:

@

Alex Abramovich

Agreed!

-

25 August 2021

at

8:41pm

Eddie

says:

In short, Charlie’s good tonight, inne?

-

26 August 2021

at

10:43am

steve kay

says:

@

Eddie

Now, I hope you are not suggesting that Alex’s incoherence is a result of looking in the mirror, comment passed on for a friend.

-

26 August 2021

at

6:00pm

Eddie

says:

@

steve kay

No, I enjoyed the article very much.

-

26 August 2021

at

1:43pm

Richard Tomblin

says:

Hard to argue that Brian Jones wasn`t gifted musically.

-

26 August 2021

at

5:49pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Richard Tomblin

not gifted in the way Watts & Taylor were. FWIW, here's Jagger:

-

27 August 2021

at

5:24pm

David Dodd

says:

@

Alex Abramovich

The Rolling Stones are very much a musical universe unto themselves, so I don't think "musical gifts" is the best way to describe the difference between Charlie Watts and Mick Taylor on the one side, with Brian Jones and Keith Richards on the other. It seems more accurate to say that Charlie Watts and Mick Taylor had a conventional mastery of their instruments that guaranteed that they would be fixtures of the British Blues Boom, regardless of whether the Rolling Stones existed at all.

-

26 August 2021

at

2:55pm

Kellan Steck- Refoy

says:

Great piece - enjoyed the Mitchum ethos ;'stillness and purposive' for context. Immersive and visual observance...

-

26 August 2021

at

6:03pm

Michelle Waits

says:

That alternate take of Lovin’ Cup makes me a nervous wreck. It’s so on the verge of falling to pieces.

-

1 September 2021

at

6:06pm

Ian Stewart

says:

This is just nonsense. One doesn't need to denigrate the others just to praise the one. Charlie Watts was brilliant, and when you talk about the stillness and the pace, you aren't wrong. But the Stones as a band are and were successful because they were *all* very talented, and their talents came together to form one of the greatest bands of all time. I note it has become fashionable to laugh at Mick Jagger - and yes, he was always something of a clown - but, as Charlie Watts himself said, there was no one better at commanding a stage, communicating with an audience. If that isn't talent, then I don't know what is.

-

8 September 2021

at

11:24am

Roland Allen

says:

I think you're dead right about Charlie but dead wrong about (the public) Jagger not being funny. His lyrics are full of wry lines and, face facts, you don't prance about like that, wearing those clothes, if you can't laugh at yourself.

Read moreWhat did he have talent for?

He was a guitar player, and he also diverted his talent on other instruments. His original instrument was the clarinet. So he played harmonica because he was familiar with wind instruments.

Did he give the band a sound?

Yes. He played the slide guitar at a time when no one really played it. He played in the style of Elmore James, and he had this very lyrical touch. He evolved into more of an experimental musician, but he lost touch with the guitar, and always as a musician you must have one thing you do well. He dabbled too much.

Brian Jones, on the other hand, may well have been the source for all of the qualities that made the Stones the Stones, rather than the Bluesbreakers or the Yardbirds. Leaving aside his contributions to their alleged lifestyles (pity Richards and Jagger for having to pretend to be teenage Brian Jones in public for their entire lives), he essentially made possible their continued reinvention through the '60s. He pressured Richards and Jagger to sound as close to the Chess Records sound as it was possible for Londoners to sound, giving them needed credibility in a crowded London blues scene. His interest in, and ability to play, exotic instruments allowed the Stones to compete in the mid-60s with the Beatles and Beach Boys and their armies of studio musicians. Finally, his interest in drones, appearing on seminal tracks like "Street Fighting Man" and "Jumpin' Jack Flash", may have helped Keith Richards to see the value in the open-tuning style he saw Ry Cooder playing. This was not only valuable for inspiring their last great period of recordings, but also, given the acoustic properties of sports arenas, may have helped the Stones survive as a live act.

In any case, none of this takes away from Watts' importance to the group as a musician. His skill as a jazz-blues drummer gave all these experiments a seriousness that many of their contemporaries lacked. Like his peers in the London blues scene, Ginger Baker and Mick Fleetwood, he helped make the British Invasion an important musical movement that the American music industry would need to reckon with, rather than a mere cultural anomaly of the '60s.