The outfits, my dear!

Sam Kinchin-Smith

Mantel Pieces, a collection of Hilary Mantel’s contributions to the London Review of Books, is published today by Fourth Estate. Each of its 20 pieces is accompanied by a fragment of related correspondence, cover artwork or other ephemera from the LRB collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. In the introduction Mantel describes the book’s contents as ‘messages from people I used to be’, but they are consistent in at least one respect: she’s always been as wonderful a writer of letters as she is of everything else.

The selection begins with the note she sent to Karl Miller after he’d published her first piece for the paper in 1987: ‘If you would like me to do another piece, I should be delighted to try … I have no critical training whatsoever so I am forced to be more brisk and breezy than scholarly.’ ‘It’s possible that I didn’t always know what I had agreed to review,’ she writes in the introduction, ‘but I learned that the paper is skilled at matching contributors to a task.’ In 1989 she was sent Jonathan Guinness’s bizarre first-person biography of his own secret mistress: ‘From now on, I am Susan Mary Taylor, born in Oldham, Lancashire, on 26 July 1944.’ ‘The Guinness book filled me with mirth,’ Mantel wrote to Mary-Kay Wilmers, ‘because I grew up quite near Oldham, so I know all about it.’

One of the pleasures of reading Mantel’s pieces in chronological order comes from tracing them alongside the parallel line of her novels: her review of a book about the medium Hellish Nell, Britain’s last witch, for example, published four years before her novel about the occult, Beyond Black (‘How cd we resist it?’ Wilmers wrote). The correspondence fills in a few more of the gaps: ‘I’ve now almost finished the first draft of my radio adaption of A Place of Greater Safety, so have dwelled extensively with the dead,’ Mantel wrote in 1997, halfway between the publication of that novel and her two pieces about Robespierre. ‘Tomorrow I am out with my Jacobin sweetheart turning over the contents of a picture library – I pity the curator.’ In a fax two years later she explains to an editor that she has ‘five portraits of Robespierre on my study wall … Not, you understand, that I like just anyone to know this.’

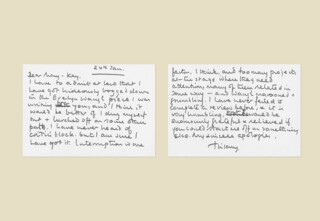

By 2005, she had found a new protagonist:

I started writing The Complete Stranger, my novel set in Africa, and left it off because it was frightening me – I hope that means it will be good, ultimately – and decided to have a go at Wolf Hall, my novel about Thomas Cromwell. Oh, the joy of having a main character who’s not neurotic! I wish I’d thought of it before. The only trouble is I have to kill off Cardinal Wolsey soon, and I’m going to miss him so much. The outfits, my dear! I wonder why we bother wearing anything but scarlet.

In 2006, however, three years before Wolf Hall was published, certain neuroses had begun to crystallise (along with a sentence structure – ‘he, Cromwell’ – that readers of the novel will recognise):

They were all so determined on incest or quasi-incest, like people enthralled by their own nightmares. Cromwell was the same age as Henry’s dead elder brother, Arthur the shadow king. He – Cromwell – made two attempts to get related to Henry, and succeeded in marrying his son to Jane Seymour’s sister, which was not bad going, since Cromwell’s own father was a violent and drunken blacksmith from Putney. Then (as a prelude to executing him) Henry accused Cromwell of plotting to marry his daughter, Princess Mary, and overthrow him. So there is an alternative history of England in which Cromwells are king. I just thought you might like to know that.

Elsewhere there is consolation for other writers (‘I have never heard of critic’s block, but I am sure I have got it’), and dramatic events playing out behind the scenes of her memoir pieces: ‘There came the moment when she said “You last saw your father in 1963, and you have never heard of him since?” And I was able to reply, “Not till three hours ago.”’

There are also emails about the episode that means, as Mantel puts it, ‘I have to live with a traitor’s name.’ ‘I’m going to begin by telling how when I was first invited to Buckingham Palace it all got too much for me and I had to sit on the floor behind a sofa and just notice feet,’ she wrote in the months before her 2013 LRB Winter Lecture on ‘Royal Bodies’. ‘Gerald says I can kiss goodbye to my damehood.’ Well, not quite, but nearly: ‘The Daily Express is sitting outside my house, phone ringing etc. My line is that there is nothing to add to the original speech. It was broadly sympathetic to the royal family and asked the press to “back off and not be brutes.” These are sad days for irony.’

The final email in the book is from Mantel to Wilmers, from last year: ‘I remember very well the first time we spoke on the phone. I couldn’t hear a word and agreed to all sorts of things.’ The last word, though, goes to Wilmers, who, in reply to a note from Mantel about her ‘deep need to keep away from the Elizabethans’ and other ‘potentially fascinating things, in case of imagination creep’ (the reason, incidentally, that there are so many pieces about the early Tudors in the second half of the book), remarked: ‘Really we just wish we could publish your emails.’

Comments