Chris Killip 1946-2020

The Editors

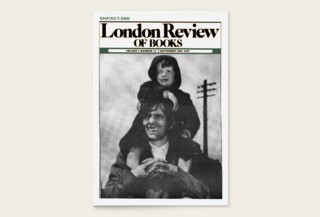

The documentary photographer Chris Killip has died at the age of 74. Best known for In Flagrante, his series of photographs taken in England’s deindustrialising north-east between 1973 and 1985, and published in a book in 1988, he also provided cover photographs for 19 issues of the LRB between 1980 and 1989. Some, such as the boy on his father’s shoulders watching a parade in Newcastle, came from In Flagrante.

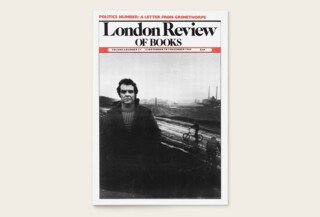

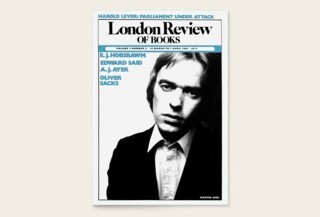

Others, such as his portrait of Martin Amis, were commissioned by the paper.

Yet others wouldn’t have been out of place in In Flagrante but were commissions for the LRB, such as the 1984 portrait of Harold Hancock, a striking Grimethorpe miner (top), photographed (in Karl Miller’s words) ‘at the scene of the crime which has been imputed to those local people who have been trying to keep warm by picking coal from the tip’. Hancock’s photograph was on the cover because he had a piece in the issue:

Monday 17 October was a different story: the police were confronted by quite a few young men: we were not running away any more. Confrontation took place on the tip – miners versus police. For a brief time we had shown that the people of Grimethorpe had had enough. The police station was stoned, and windows broken. By three in the afternoon the top end of Grimethorpe was sealed off by three hundred riot police; by 11 o’clock nearly six hundred riot police were running amok in the village, clubbing anyone within arm’s reach. The next day, Tuesday 18 October, people in the village were running a gauntlet of foul-mouthed obscenities, mainly levelled at women and young girls, from police officers still clad in riot gear.

A book of Killip’s photographs of the Isle of Man, where he was born, was published by the Arts Council in 1980, with an introduction by John Berger. Peter Campbell reviewed it for the LRB:

These pictures could only have been made, Killip says in his introductory letter, because ‘I could be named and placed by the people I photographed because of my grandmother, or because of my father.’ This knowledge of relationship between photographer and subject seems to me to come much closer to explaining the force of the pictures than do Berger-like speculations about the subjects’ experience. It reminds one that these are individuals, that there is no convincing science of physiognomy, and plenty of evidence that people do sometimes read things into pictures that are demonstrably not there.