Social Distancing in Iran

Arianne Shahvisi

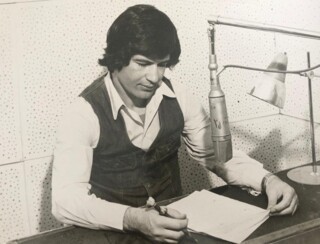

Laurel and Hardy reruns often played on Iranian television when I visited as a child. Wholesome, black-and-white slapstick didn’t need to be censored. In the Kurdish version, Oliver Hardy’s voice was dubbed by my uncle, Hashim Shahvisi, who was for decades a popular radio presenter. A year ago, he was in hospital in Tehran with an unspecified illness. My father spoke to relatives every day without getting any closer to finding out what was wrong.

Social interactions in Iran are dictated by a form of etiquette known as taarof: an elaborate, indirect manner of speech and behaviour. Layers of symbolism, verbosity and insincerity are intended to smooth over conflict, ease interactions, and keep certain truths buried. It’s a form of social distancing, if you will, putting space between what is meant and what is said. As the social scientist Kian Tajbakhsh has put it, ‘in the West, 80 per cent of language is denotative. In Iran 80 per cent is connotative.’

Taarof guarantees that you will be offered food if you visit someone’s house, but it also demands that you decline. By cycling through several rounds of offering and refusal, you and your host may eventually surmise the truth through the subtle particulars of your evasions. Perhaps they’d really like to feed you and will be insulted if you don’t oblige them; maybe you’re really hungry.

To outsiders, taarof is often missed, misunderstood, or misused as a basis for racist stereotypes. During the nuclear negotiations, Wendy Sherman, Obama’s under secretary of state for political affairs, said of Iranians that ‘deception is part of the DNA.’ Taarof may be an ancient custom, but it isn’t evidence of dishonesty any more than it’s a cute cultural quirk. It’s a protective measure whose pragmatic value is obvious in the situations in which it is used.

Uncle Hashim never left hospital, and died a month later. We planted a cherry tree in my parents’ garden in Essex, three thousand miles from where he is buried. We hadn’t been at his bedside and we couldn’t be at his funeral. It wasn’t clear exactly what had happened. Perhaps my father didn’t ask the right questions in the right way to break the spell and expose the gravity of it all; he has been in the UK for forty years, and taarof is convoluted even for the well practised. Perhaps, being too distant to help, he didn’t really want to know the truth.

Two of the hardest realities of the Covid-19 lockdown in the UK are knowing there isn’t enough medical equipment for everyone, and being unable to be with loved ones in their final moments. Both have long been the reality for many of the three million people in the Iranian diaspora.

US-led sanctions have devastated Iran’s economy. Oil exports have plummeted and living costs are through the roof, with food prices rising every year. Essential medicines for cancer, heart disease and respiratory problems are in short supply, and menstrual products, nappies, and formula milk are prohibitively priced. As the coronavirus has raged through Iran, hospitals have struggled to get PPE, test kits and respirators, which has undoubtedly contributed to the unusually high death count. In February, the foreign minister, Javad Zarif, said the US had ramped up its ‘economic terrorism’ to ‘medical terror’ by refusing to lift sanctions. Last month, in desperate straits, Iran asked for a $5 billion emergency loan from the IMF. The US blocked it.

After my uncle died, my father had to send some legal documents to Tehran, but hit another wall. Posting a letter to Iran is more or less impossible. (Look at the ‘sanctions’ section on the Royal Mail website.) He had to wait for a friend to travel there and hand it to my cousin in person in the airport. There are networks of people in the Iranian diaspora who do this for one another: meeting their friends’ and neighbours’ relatives in the arrivals lounge to exchange wads of notes, letters, medicine and gifts. They become, by necessity, smugglers, going in loaded with cash, and leaving with cases of nuts, homemade jam and lavashak.

Iran eased its lockdown at the beginning of the month in an attempt to jump start the economy, but the infection rate began to recover momentum. On Sunday evening, restrictions returned to a province in the south-west of the country. Last week, the Central Bank announced plans to knock four zeros off the rial and change the currency’s name to the toman, as if renaming something could make the problem go away.

Comments