Dancing to Numbers

Owen Hatherley

After the death of Florian Schneider-Esleben was announced on Wednesday, one of the most shared video clips on social media was of a group of young black Americans dancing to Kraftwerk’s 1981 track ‘Numbers’. It had been broadcast on the BBC last year, as part of Jeremy Deller’s lecture to an ethnically mixed school in London on dance music and politics in Britain, Everybody in the Place. Deller said that whenever he feels sad about the state of the world, he watches this clip. Snipped from a 1991 episode of the Detroit area cable TV programme The New Dance Show, it appears to present a utopian moment, a dissolving of all the boundaries, usually so carefully policed, of race, class, technology and authenticity. It points to the conjunction that made Kraftwerk so important: their forging of a link between the two most revolutionary things that happened in the arts in the 20th century, the two movements that transformed the most people’s everyday lives – Central European modernist design and African-American music.

Florian Schneider (he dropped the double-barrel in the mid-1970s) formed Kraftwerk in 1970 with Ralf Hütter, an architecture student and classically trained avant-garde musician. Schneider’s father, Paul Schneider-Esleben, was one of the leading West German architects of the 1960s. Kraftwerk are often compared to the Beatles, but in class terms this is a little as if John Lennon had been the son of James Stirling or Robert Matthew, rather than a merchant seaman. Born in 1915, Schneider-Esleben was among the first West German architects to rediscover, in the 1950s, the modernist design that had thrived in the Weimar Republic, all but forgotten by the end of the Nazi era. Schneider-Esleben’s major projects, such as the sleek Commerzbank tower in Düsseldorf, show a heavy Weimar influence: clear, linear and rational.

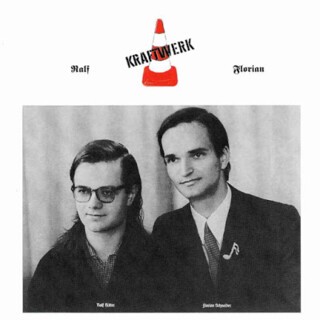

His daughter, Claudia, became a gallerist in Cologne, and his son spent the late 1960s on the fringes of the Rhineland avant-garde scene. Among the exhibits in a recent exhibition on West German Pop Art at the Düsseldorf Kunsthalle, Singular/Plural, was a photograph of a young Florian, naked next to a swimming pool, already mastering an utterly deadpan look. When Kraftwerk moved towards a severe, industrial-corporate aesthetic modelled on the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism, it was under Schneider’s influence. On the cover of the group’s third album, Ralf & Florian (1973), Ralf is still a scruffy hippy, but Florian, with his tailored suit and side parting, looks like a member of ‘Kraftwerk’.

Hütter and Schneider used to tell interviewers that their project was to reopen the Constructivist/Functionalist/Futurist movements interrupted in the early 1930s by Hitler and Stalin; in this, they were retro-futurist from the start. On the back of The Man-Machine (1978) there are two interesting credits. One is to El Lissitzky, from whom the group lifted the colour scheme and typography for the album cover; the other is to Leanard Jackson, an African-American sound engineer who had worked with Norman Whitfield and Rose Royce, and was apparently hired by Kraftwerk to make the record sound ready for dance floors. The group had presumably heard that their previous album, Trans-Europe Express, had been a hit at parties in the South Bronx. It is often said that Jackson was surprised on meeting Kraftwerk to find that they were white.

Kraftwerk’s influence on English synth-pop is patent, but their effect on the overwhelmingly black scenes of hip hop and electro, which came out of the Bronx, as well as Chicago house, Miami bass and Detroit techno, has been enduringly controversial. It would be absurd to suggest Kraftwerk were the sole influence on these genres (and Kraftwerk’s emulation of the mechanised sounds of trains and roads can easily be traced to the J.B.’s or Duke Ellington) but the links aren’t hard to spot. The first electro track, released in 1982, was Afrika Bambaataa’s ‘Planet Rock’, which plays the melody of ‘Trans-Europe Express’ (it isn’t a sample) over an approximation of the beat from ‘Numbers’, which also formed the basis for nearly every Miami bass track, and has resonated through hip hop and R&B from the US south well into the 21st century. The cover of the first widely distributed Chicago house record, Jamie Principle’s ‘Your Love’, was a tribute to The Man-Machine. ‘Sharivari’ by A Number of Names (1981), the first Detroit techno track, is in serious hock to ‘It’s More Fun To Compute’, which had come out months earlier; ‘Technicolor’ by Juan Atkins, a.k.a. Channel One (1986), is as obvious a Kraftwerk tribute as Oasis’s most shameless Beatles references.

As to why this should be controversial, well – to call Kraftwerk Eurocentric would be putting it extremely mildly. A vision of ‘Europe Endless’, as one of the tracks on Trans-Europe Express is called, is always going to be chilling for anyone who has seen what European expansion across the globe has meant for those subject to it. To place two upper middle-class Germans at the centre of African-American electronic music may seem suspiciously – offensively, even – neocolonial. But as Kodwo Eshun pointed out in his 1998 treatise on musical Afrofuturism, More Brilliant than the Sun,

those of techno’s supporters who insist that Detroit brought the funk to machine music will always look for techno’s Af-Am origins to answer these crits. Sun Ra? Herbie Hancock? Kraftwerk’s love of James Brown? All of these are routes through techno – yet none work, because Detroit techno is always more than happy to give due credit to Kraftwerk as the pioneers of techno. Kraftwerk are to techno what Muddy Waters is to the Rolling Stones – the authentic, the origin, the real.

The most militant and politicised of Detroit techno producers have been the keenest to make the connection, whether it’s Marc Floyd of Underground Resistance calling an extremely Kraftwerkian track ‘Afrogermanic’ (1998), or Drexciya imagining an elaborate alternative history in which escapees from slave ships created an advanced, modernist underwater civilisation, ‘Aquabahns’ and all. Producers from Bambaataa to Mike Banks have said they didn’t see Kraftwerk as white, or as German; Juan Atkins has said he ‘had doubts as to whether they were actually human’. Kraftwerk were celebrated for being what they said they were: ‘The Robots’.

But why share the New Dance Show clip now, of all the dozens of Kraftwerk videos that could be used to celebrate Schneider’s life and work? Surely because it seems to capture a moment of possibility, where all the things that keep people apart, in their segregated sections of society, are suddenly removed. ‘Numbers’, insofar as it has lyrics, is a series of counts, upwards and downwards, in German, English, Russian, Italian, Japanese, running in syncopated lines above a relentless electronic funk beat. In their astonishing sequence of albums from Autobahn in 1974 to Computer World in 1981, Kraftwerk seemed to be aiming at a kind of electronic Esperanto, an imaginary universal language that anyone could learn, anyone could speak, anyone could dance to (just as the utopian socialist modern designers of the 1920s had dreamt of universal systems detached from the hierarchies, nationalities and borders of the past). The clip shows that the experiment worked: you could dance to numbers.

Comments

-

9 May 2020

at

1:28pm

Robin Durie

says:

There's a hegemonic privileging of Kraftwerk amongst cultural commentators from which this blog only barely deviates.

-

16 May 2020

at

1:21am

Chico Cornejo

says:

@

Robin Durie

Apparently, you can't raise your thighs as high as your eyebrows.

-

13 May 2020

at

12:17pm

Willem Koster

says:

Volgens mij was en is Esperanto geen denkbeeldige maar een ontworpen taal, in 1887 bedacht en jammer genoeg feitelijk nooit tot 'grootgebruik' gekomen.

-

16 May 2020

at

1:05pm

Tim Archer

says:

Actually, those farty noises were about the only thing you could get out of the synths of the day.!

-

16 May 2020

at

6:06pm

Ken Currie

says:

I love Kraftwerk but I'm just wondering what Owen Hatherley means when he says : "It points to the conjunction that made Kraftwerk so important: their forging of a link between the two most revolutionary things that happened in the arts in the 20th century, the two movements that transformed the most people’s everyday lives – Central European modernist design and African-American music."

-

16 May 2020

at

8:34pm

Seth Edenbaum

says:

I always amazes me how modernist idealists turn art produced to make dystopia bearable –an art that reinforces the only reality the artists know– into something fitting writers' own happy talk idealism.

Read moreOn the one hand, it's notable, if not unsurprising, that Schneider's death should merit a post here at the LRB, but that Tony Allen, a musician of comparable - if not greater - influence, & one of rather more interesting cultural-political significance, should pass unremarked.

On the other, the overly curated spectacle of Kraftwerk tends to obscure the altogether richer musical achievements of bands such as Neu!, Harmonia & Cluster (or even Can).

It is indeed a/be/musing to realise how musically anachronic and Eurocentric critique can be when it comes from the same old sources.

It is a pity, but I ain't sad...

My parents were born around 1932, in Scotland, my father a welder, my mother a bus conductress among many other occupations. They lived through the 20th century and both are gone now. I'm just wondering how their everyday lives were transformed by Central European design and African-American music given that they weren't remotely interested in either. The only impact Kraftwerk had on their lives was that I perhaps played them a bit too loudly in my bedroom.

Sometimes it's a good idea to think twice before making huge sweeping statements.

If you want to think of Kraftwerk you need to think of Richter's nihilism and "nostalgia for the real" , Böll's Billiards at Half-Past Nine, and Deutschland im Herbst. Post-war Germany was an autistic state. Richter said once that for Germans to believe in anything is disaster, so refusal of all belief was the only option. Alienation, anomie, capitalism and the closet.

Ask Juan Atkins about the decay of Detroit, autoworkers being displaced by robots, or surrounded by them. Ask him about white flight. Ask him about the past; don't let him rewrite it now that he's a big shot and bougie. It's always a mistake to take successful artists at their word about the origins of their art. Picasso's best work is as f'ked up as Warhol.

And urban black America had discovered Kraftwerk by 1977.

Computerworld was their first album in the US that went beyond the underground.

I await your rewriting of Weimar Berlin as a happy time and full of hope.