Mound of the Dead Men

Arianne Shahvisi

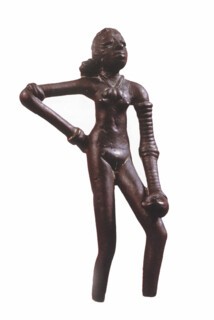

Perhaps the oldest bronze statue in the world is the Dancing Girl, a 4000-year-old, 10 cm figure found in 1926 at the Mohenjo-daro archaeological site in Sindh, in what is now Pakistan. In Sindhi, Mohenjo-daro means ‘mound of the dead men’. The statue – now in a museum in New Delhi – depicts a gangly teenage girl whose body language looks remarkably modern: insolent and unimpressed.

When I studied in Oxford a decade ago, I often passed under the stone statue of Cecil Rhodes on the front of Oriel College as I walked to the philosophy department on Logic Lane. Rhodes meant nothing to me in those days. My eighteen years of education had not once mentioned colonialism, and my head was often down as I trudged through the streets, falling into the common error, noted by Alan Bennett, of ‘confusing learning with the smell of cold stone’.

Most of my time was devoted to working through the hefty reading list. Looking for a role model, I first scanned it for women’s names. I could see only one, but it appeared time and again: Hilary Putnam. I clung to the thought of such an eminent woman philosopher until Putnam was referred to in a seminar as ‘he’. I took the disappointment silently.

It goes without saying that there were no Black philosophers on my reading list in Oxford, no people of colour, and none working outside the western tradition. Statues, like reading lists, tell us how to assign credibility and moral approbation. This realisation wasn’t new to me. When Winston Churchill was described at my primary school as a hero, at first I assumed there must be some confusion. My father is Kurdish, and at home Churchill was known for his view on using chemical weapons against Kurds:

I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum. It is not necessary to use only the most deadly gases: gases can be used which cause great inconvenience and would spread a lively terror and yet would leave no serious permanent effects on most of those affected.

He said that in 1919. By the time I heard his name in class, it was the early 1990s. In 1988, when I was one, my mother had held me in her arms as she shook a collection box outside Woolworths on Accrington High Street to raise money for the people who had survived Saddam Hussein’s massacre of Kurds in Halabja. Five thousand people had dropped dead in the streets, their skin blistered, as mustard gas and nerve agents fell from the sky, and ten thousand were seriously injured. Three decades later, birth defects and cancers are ten times higher than in neighbouring regions.

My teacher presented Churchill as an uncontroversial luminary, and in that moment I had to divide myself in two: the side that would go along with the charade and please the misguided teacher, and the side that knew what was right and saw that there were other stories, too. One word for what the teacher was telling us is propaganda, and that may be the best way to understand statues of slave traders in a country that doesn’t teach its own colonial history. It is telling that so many people have this week argued we are supposed to remember these dead men for their philanthropy.

‘I contend that we are the first race in the world,’ Rhodes once said, ‘and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. I contend that every acre added to our territory means the birth of more of the English race who otherwise would not be brought into existence.’ In his will he bequeathed large sums to Oxford University to found the Rhodes Scholarship and left £100,000 to Oriel College, which his statue now decorates.

Rhodes still stands, but unless the college cuts down his stone likeness from above its entrance, it won’t be long before he’s lassoed down to find a more fitting resting place in the silty bed of one of the muddy waterways that criss-cross the city. In the meantime, a statue of Belgium’s brutal colonial monarch King Leopold II has been removed, as has a bronze cast of the slave trader Robert Milligan, which until earlier this week stood outside the Museum of London Docklands. Across the United States, statues of Christopher Columbus are toppling. A mound of dead men is forming.

Watching the statue of Edward Colston break the surface of the water of Bristol Harbour, I remembered flipping coins into wishing wells as a small child. Until 1992, the penny was made of bronze, so those early wishes were made of the same stuff as Colston’s effigy. The practice of throwing coins into wells is an ancient tradition, and may have emerged because copper (a component of bronze) has oligodynamic properties: it kills bacteria, making water safer to drink. Colston’s statue was seven feet tall. That’s a lot of wishes. It’s a shame they dredged it up today: all that bronze at the bottom of the harbour might have made Bristol’s waters a little cleaner.

Comments

-

12 June 2020

at

10:03am

Tom Adlam

says:

Beautiful writing. It's very painful first to acknowledge and then to accept that the heroes we grew up with have feet of clay. But as long as we continue to celebrate, even venerate, men of power, we are going to be disappointed. Difficult times are ahead.

-

13 June 2020

at

2:57pm

wse9999

says:

Let the truth out. Marvellous. But all the truth.

-

13 June 2020

at

3:01pm

Robert Davies

says:

That is a very thoughtful and imaginative exposition of the issues around Britain’s colonial history. It is interesting that the Museum of London Docklands is mentioned because it was in there that the full magnitude of the slave/sugar trade was brought home to me.

-

13 June 2020

at

3:06pm

davidovich

says:

What are the terms of Rhodes will with regard to the eponymous scholarship? Do we get to throw Gareth Evans, Bob Hawke and Tony Abbott into Oxfordshire’s silty waterways?

-

13 June 2020

at

3:37pm

R Bunting

says:

@

davidovich

Can we not keep the (mostly benign) Rhodes Scholarship separate from the tarnished reputation of the man himself?

-

13 June 2020

at

3:54pm

Nico Pollen

says:

Most of our ‘hero’s’ were flawed. Some more gravely than others. Colston was a slave trader, who shipped a human cargo from Africa to the Americas, and sold on the survivors. That’s what he was, that’s what he did. He funded Bristol with some of his ill gotten wealth.

-

14 June 2020

at

9:43pm

steve kay

says:

@

Nico Pollen

If Churchill had died in 1930 he would still have been remembered here in South Wales.

-

13 June 2020

at

6:31pm

David Campbell

says:

My first awakening to how equivocal memorial statues can be dates to 1945 when, aged eleven, I returned from wartime USA, and saw that FDR was being commemorated in Parliament Square, no less. The Republican family I had stayed with in America were keen Republicans, to whom Roosevelt was a cretinous monster who had held onto power for FOUR TERMS, in flagrant breach of the Constitution. I couldn't believe my countrymen were so ignorant!

-

13 June 2020

at

9:46pm

Marmaduke Jinks

says:

Bad men can do good things; and, of course, vice-versa.

-

14 June 2020

at

1:41am

Matthew White

says:

I don't understand why it seems to come as such a surprise to so many that our past great men (and women) held what are now regarded as obnoxious views on race and colonialism. They were products of their time (a cliché I know but no less true for being one), and anyone with any care to read history would know it. Biographers have not shied away from these issue in the last 50 years, in fact there's been a considerable industry in exposing these famous former leaders for these views. Society as a whole has preferred to honour them for the good they did do, the money they provided to good causes and their redemptive qualities. I don't think that means we are blind to the bad things, as any civilised society would be. Telescoping the sins of the past into the present for the purpose of wrecking established cultural institutions is not civilized. And the legitimate concern one might have about mobs gleefully pulling down statues in our great cities in their new found zeal is that it may start with statues but can end with people.

-

14 June 2020

at

11:53am

Jake Bharier

says:

@

Matthew White

The use of collective terms ("we", "our", "Society as a whole") shows a blindness to the very points that Arianne Shahvisi makes in her original post. Just to pick on one of these terms: the statues of Edward Colston, or Robert Clive, (see https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/11/robert-clive-statue-whitehall-british-imperial ), or all those Confederate generals, were not erected by "society as a whole", but by a very select group who were determined to impose their own version of history.

-

14 June 2020

at

5:41pm

James Calhoun

says:

I really appreciate your words and perspective. I also want you to be aware that I am quoting you in my forthcoming book. Should you desire more details about its release date etc. I can be reached @ jimicalhoun.com

-

15 June 2020

at

6:54am

wse9999

says:

While we on problematic statues in the piazza.. how on earth can any of Julius Caesar be left in pride of place in Italy?

-

16 June 2020

at

9:57pm

Devendra Kodwani

says:

Kudos for writing a timely reminder. I knew about Rhodes Scholarships as a great scholarship scheme that offered opportunity for bright people from around the world to study at Oxford university. I had no idea until reading this piece and subsequent brief search online that the scheme was sponsored by Cecil Rhodes who espoused and furthered British imperialism.

-

18 June 2020

at

9:55am

neddy

says:

I do enjoy your writing Ms Shahvisi. Although to me the statue says: "you want some of this? In your dreams, boy!"

Read moreI’m an old white chap who’s read widely the history both sides of the Atlantic.

So the reality is the long journey to modern liberal democracy was paved with much shocking "illiberal" behaviour, like mass religious violence in 12th to 14th C [Crusades etc]., then religious civil wars of 16th and 17th C, plus endless rounds of European national wars, then from c1500 over 4 centuries of wholesale competitive imperialist violence abroad, on 3 continents, especially the Atlantic slave project.

A shocking journey.

But not just a Western one. Near all traditional societies are plagued by identity abuse.

But the strange and uncomfortable irony is that this Western journey did eventually produce an antidote in universal identity-blind '”liberal democracy”.

Universal meaning no identities are favored: by race, place, religion or gender.

Though implementing this model is never easy, because of the residual appeal of identities.

However another reality today is that more "racism" by far occurs in many non "Western" lands where identities of whatever stripe are promoted, propagated by authorities, in Africa, Mid East and Asia.

Others were more mixed. If Churchill had died in 1930 he would not be remembered. He was a journalist, an imperialist, something of a politician. If he had died before summer 1939, there would be a footnote in the histories, that he was one of the few public figures who spoke out against Nazi Germany as a threat to, at least , Europe.

I really don’t know how much he was a great war-leader, how much a figure head who had the sense, and the luck, to work with the very able. Probably a bit of both. But this was the moment where he proved his capacity, where he was needed.

One line outline - leader when it counted. Full history - a very flawed leader, but genuinely a part of UK history.

Later, in Berlin in the 1970s, I found that Stalinallee had been robbed of its centrepiece, a truly massive statue of Stalin in pale green marble (as I remembered it from a schoolboy visit in the 1960s). I had thought then and still think now how brilliantly conceived it was. Stalinallee, in its original form, curved majestically in the middle. Here, offset to the side, Stalin's pyramid-like monument slowly and dramatically declared itself. A condemnation of the personality cult if ever there was one. On artistic, political, historical and propaganda grounds I felt it would have been far better left as it was. I still feel that way about most memorial statues, including the rather drearier ones of Rhodes and Colston.

No-one’s perfect. Well, there was one bloke but they nailed him to a cross 2,000 years ago.

We should all be looking forward and not back. Take the Rhodes Scholarship: there are many people walking around right now, who hold what we still quaintly call 'left-wing' views about structural discrimination and historical injustices committed by Western democracies (they are in fact orthodox views), and sneer about Oxford University and the privilege it represents, but who happily applied for and took Rhodes's money for several years of their university educations, and who have benefited from the prestige of having held the scholarship, but I doubt they will be paying the money back any time soon. How pure should we be? At what point is a line drawn to guard against our complicity? If you adopt a retrospective method, who is not a sinner?

Would it not be better, rather than live in an age of denunciation, to accept the imperfect nature of the past, and indeed of ourselves, but look forward to making the best improvements we can for as many people as possible, but in a positive spirit and not a destructive one?

And while I'm at it, is not "established cultural institutions" another of those collective terms?

I always recall the one in Civedale, where the man wintered his assistants.

Reminded as we are by nearby review of WAR FOR GAUL.

Having experienced first hand some consequence of colonisation/decolonisation of India which ultimately ended with partition of India, I now have a slightly different feeling about Rhodes Scholarship.

Partition of India in 1947 meant my parents and grandparents from Sindh found themselves as refugees on outskirts of a large city in western India. Being born in a refugee camp and growing in the dirty streets with parents struggling to make two ends meet did not though spoil the joys of childhood as we thought that is how normal living was.

The Sindhi refugee community was the only community in that refugee camp. The community set up its own schools where I studied, luckily for me in mother tongue Sindhi until higher secondary. Sadly those schools have now converted to English medium schools which is not unusual for other vernacular medium schools in India.

It is knowing Sindhi language and being aware about bit of Indus Valley civilisation that I know that Mohenjo Daro literally means ‘Mound of dead people’, not ‘mound of dead men’. Without undermining the power of metaphor in this article it seemed worth noting this translation accurately. A friend with whom I shared the article alerted me to this translation error which I hope the writer will not take exception to as the article itself is brilliant and timely reminder.