‘We took many steps and saw many sights’

Laura Beers · D-Day

The news that Donald Trump would attend the 75th anniversary D-Day commemoration in Portsmouth as part of his state visit to Britain this week met with a mixed reception from the event’s organisers. The Liberal Democrat council leader said that the president’s presence would lead to security concerns and protests, and ‘veterans will be pushed out from the coverage’. But the head of the council’s Conservative group welcomed the news: ‘Having Donald Trump there for the vast majority of those veterans will make it a spectacular event.’

Of the 156,000 British, Canadian, American and other Allied troops who sailed from Portsmouth for the Normandy beaches in June 1944, fewer than 1500 are still alive. They are all in their nineties, at least. My grandfather, a D-Day veteran who died in 1998, would be 103.

Shortly before resigning as defence secretary, the hard Brexiter Gavin Williamson said: ‘Britain must always keep the legacy of that special generation alive. I urge people to join our Armed Forces in showing that all of us, young and old, will never forget the price they paid for the freedom and peace we now enjoy.’ As politicians make use of the anniversary of D-Day to retell their own stories about the present, we risk losing sight of the individuals who made up ‘that special generation’.

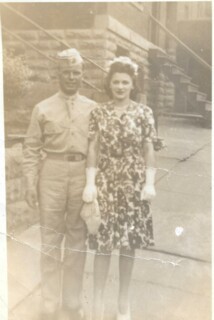

My grandfather rarely spoke about the Second World War. I interviewed him about his wartime experience when I was in high school, but coaxed very little detail out of him. Conscripted in 1941, he was a non-commissioned officer in the 200th Field Artillery Battalion of the US Army. He joked that his 29th birthday was marked by fireworks (16 December 1944, the start of the Battle of the Bulge), and confessed that when he heard of the bombing of Hiroshima, he felt simply relief that he would get to go home instead of being sent east.

After he died, I read the letters – more than a hundred of them – that he wrote to my grandmother while he was in the army, including his description of the D-Day landings:

We spent about four days on our LST [Landing Ship Tank] in anchor just off shore. Finally we sailed for the scene of the crime. This was a 24-hour slow journey during which time we rocked and rolled. Few became sea sick though. This must have been due to the four-day layover off the English coast during which time we slowly acquired a pair of sea legs. Twenty-four hours after the initial assault, we laid anchor off the French coast. We were due to go in immediately, but were held up due to the stiff resistance given the infantry so we watched events from our ship for 24 hours before we landed. We hit shore D+2 which means two days after D-Day.

After wading ashore, he felt

relief and happiness realizing we were in France at last. Relief was from all the worries and suspense we all built in ourselves during our final days of preparation. We had no cause to worry for our infantry took care of everything.

The toll on the infantry, however, was grim. Marching to their position,

we saw all the results of the previous 48 hours of fighting. Dirty and tired soldiers were standing alongside the roads. Every now and then one would ask us, what outfit, bud? When we would yell back artillery, they would usually say, boy are we glad to see you. With each step taken and new sight we saw our esteem for those boys mounted and we took many steps and saw many sights.

I started teaching modern history in 2007. Some of my students then were born after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Next year, many of my incoming students will have been born after 9/11. I have thought a lot about how to teach the history of events whose immediate social, cultural and political impact I experienced and still vividly remember. I struggle to contextualise the ‘truth’ of those events as I understood them at the time, and their ongoing impact on my view of past and current events, with the historical narrative that I try to place them in for my students.

Politicians continue to use the history of the Second World War to justify a range of positions – including both for and against the UK’s membership of the European Union. There are fewer and fewer voices that can speak with first-hand authority to the relationship between wartime service and present politics. Individual experiences should not be mistaken for higher truths, and distance often lends perspective. At the same time, there are ever fewer Second World War veterans who can wield the authority of their own experience against a willful misappropriation of their history.

Comments

In recent years, to my continued amazement and disgust, our politicians have attempted to stoke patriotism by ballyhooing the Canadian taking of Vimy Ridge in 1917 -- soft-pedaling, of course, several inconvenient facts (for example, they sometimes imply it was a solely Canadian achievement, when most of the leadership and many of the accompanying fighting units were British).

A recent book, "The Vimy Trap", confirmed my suspicion that this is a recent phenomenon -- that there was little or no public glorification, in the latter-day sense, of this or any other First World War battle when those who had fought in that war were still able to respond.