On Photographing Leon Kossoff

Toby Glanville

I first met Leon Kossoff at Willesden Junction, down by the railway tracks, in 1995. I was there to take his photograph for the catalogue of his show at the British pavilion in Venice that summer. The following year I took his portrait for his retrospective at the Tate. I photographed him for the last time in 2013, for the catalogue of his show at the Annely Juda gallery. The idea was to meet at Arnold Circus, where Leon had grown up, and take pictures there. Afterwards we had coffee in a café on Calvert Avenue, the street where Leon’s father had run his bakery. I sent the pictures to Leon and he didn’t very much like them.

He asked me to go to his house in Willesden and photograph him in the garden, down by the railway tracks – we had come full circle. It was a cold blustery spring morning. Leon wore a woollen hat and a coat as we walked down the garden but took them off when we were ready to take the photograph. The sun made a brief appearance.

When I arrived at the house Leon had opened the door and gestured towards a large artist’s folio, secured by cotton ribbons, sitting on a sideboard. I opened it. Inside was one of his etchings from Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows. ‘It’s for you,’ he said.

Also on the sideboard was a piece of stone that a friend had recently brought from Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire. ‘Look at this!’ Leon said, picking up the rock.

As we were talking, Leon’s wife, Peggy, came down the stairs. For a split second, an extraordinary moment, I felt as if I was witnessing one of Leon’s portraits of her walking towards us. Peggy in the flesh, and Leon’s image of her in paint, were all but the same.

Leon had something of a child’s awe and excitement at the sheer wonder of being alive, of looking at the depth of beauty in the world. ‘It’s what turns me on!’ he exclaimed that day at Arnold Circus.

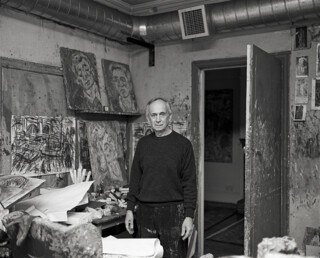

‘Yes,’ he once said, standing for a picture in his studio, his arms dropped straight by his sides, dressed all in black, hands like a gunslinger’s: ‘I felt something happen there.’ When I got the pictures back I saw what he meant. Something had happened. The kinetic tension in his body, the vitality of his gaze, had indeed somehow been recorded on film.

That morning at Arnold Circus, as I approached him with my camera, he exhorted me to ‘Take a risk! Take a risk!’He wasn’t referring to the photograph I was about to take so much as offering me a lesson in life. He took risks every day in the work he made. Every drawing, every painting was a venture into the unexplored.

Another time, at his studio, he opened a door to a room leading off the hallway. It was more or less completely occupied by a green table tennis table. ‘There, what do you think?’ he said, pointing towards a very large painting leaning against the wall behind the door, its base resting on the table. It was one of his glorious depictions of Christ Church, Spitalfields, soaring into the London sky. The juxtaposition with the ping-pong table seemed to speak to the nature of Leon’s playful and serious genius.